Bertram Mills

From Circopedia

Contents

Circus Owner and Director

By Don Stacey

The death of Bertram W. Mills (1873-1938) from pneumonia on April 16, 1938—the date on which his tenting circus was due to open at Luton for its 1938 tour—was a momentous event in the history of the British circus. Within five hours of the announcement, the boardings for the evening newspapers in London were proclaiming "Bertram Mills Dead." His name was truly a household one: One national newspaper announced the "Death of Britain’s Nº 1 Showman" and the "King of the Modern Circus," indicating the unrivalled position in which the showman was revered.

The status in which he was regarded led to a French circus critic describing him as "the renovator of the British circus," and throughout the British Isles, the show he had created in 1920 had become known as "The Quality Show"—a title it bore proudly until its closure in 1967. Without a shadow of doubt, Mills did indeed prove to be the saviour of the British circus for his generation, and perhaps, the United Kingdom will never see another era in which this form of entertainment was held in such reverence.

Lady Eleanor Smith, a great British circus lover and one of the founders of the Circus Fans’ Association of Great Britain, described Mills, always known as "The Guv’nor" to his staff, as "a short, stocky man with a bald head, a ruddy pugnacious face, a grey moustache, and twinkling, shrewd blue eyes. His eyes were as blue as the cornflower he invariably wore in his button-hole. He would have looked undressed without that cornflower…"

The National Reform Funerals (Mills and Sons) Ltd.

Bertram Wagstaff Mills was born in London on August 11, 1873. He was the son of Halford Lewis Mills of Smarden, Kent, and Mary Fenn Wagstaff. Halford Mills was the proprietor of a coach building firm in Paddington, London, and he owned small farms in the country, one at Harefield, the other at Chalfont St. Giles—the latter being where he stabled his horses for rest periods.

Bertram Mills spent most of his childhood at Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, learning to ride there and developing a love of horses. He left school at the age of fifteen and started at the bottom of his father’s business, washing down the coaches, which were an important form of transportation at that time. Within a year, he was driving four-in-hand (a coach pulled by four horses) from London to Oxford. Eventually, his love of coaching led him to exhibit carriages at major horse shows all over Europe, and his love and knowledge of horses led him to becoming a prominent judge on the international horse show circuit.Bertram’s grandfather was a Baptist preacher who had started the Reformed Funeral Company Ltd. in London, whose history can be traced back to 1872. When Bertram Mills entered his father’s business, they began importing American carriages, and the coach building side of the business was carried simultaneously with that of the undertakers.

In 1910, the name of the company was changed to Mills and Sons Ltd., and in 1938, it was renamed the National Reform Funerals (Mills and Sons) Ltd. One of the company biggest assignments would be in 1930, when the R.101 airship, on its inaugural flight of the Empire, crashed in Beauvais, France, with the loss of many lives, and Bertram Mills’ firm was asked by the Air Ministry to undertake the execution of the funeral arrangements in France and to bring back the bodies in England.

It is assumed that the coaching and funeral businesses were wound up after the death of Bertram Mills in 1938, as no reference was made to them by his sons and successors—and probably, the running of a funeral business was considered incongruous with that of a popular entertainment company.

In 1901, Bertram W. Mills married Ethel Notley, the daughter of a farmer, William Notley, who came from Thorndon, Suffolk. They had two sons, Cyril Bertram, born on February 27, 1902, and Bernard Notley, born on May 10, 1905. During the First World War, Bertram Mills served his country in the Royal Army Medical Corps, gaining the rank of Captain.

But when he returned to civilian life, he found that the coach building industry was declining, thanks to the growing development of the motorcar. This was where, as he cast around for fresh business opportunities, the circus came into his sphere.

A Man Of Many Interests

Bertram Mills’ interests outside his coaching and funeral company and then the circus were quite varied. He was a member of the London County Council for East Fulham, London, from 1928 to 1934, and for Clapham from 1934 to his death. He was also a member of the special committee of experts for the British Board of Film Censors, President of the Showmen’s Guild of Great Britain and Ireland, Chairman of the Entertainments Licensing Committee of the London County Council, Chairman of the Inspection of Films Sub-Committee, and Chairman of the Sunday Entertainment Sub-Committee.

He was a Freeman of the City of London, and a Liveryman of the Loriners’ and Farriers’ Company, and, in the year of his death, he had been adopted as a prospective Conservative candidate to represent the Isle of Ely at the Parliament. Furthermore, he ran coach services between London and Brighton and London and Oxford, bred horses, and judged at top international horse shows. Although Mills, by virtue of his interests in horses, already had a knowledge of the circus world, his entry into the circus industry happened virtually by accident.

He had many influential friends and, on one occasion, he was invited to attend a performance of Fred A. Wilkin’s Great Victory Circus and Allied Fair at the Olympia exhibition hall in London. It was the first post-war entertainment staged there, from December 1919 to January 1920. One must assume it was by no means a poor show since it included the famous Carré liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. horses; The Pissiuttis’ riding act; the clowns Gobert Belling, the Benedetti Brothers, and Theodore and Partners; Mona Connors’ equestrian act; the Flying Rainats from France; and Captain Woodward’s sea lion act. In fact, Mills would later employ some of these acts.

However, whatever the quality of the show put on by Wilkins at Olympia actually was can only be a matter of speculation. But it is true that the performance "bored [Mills] almost to tears." When pressed for his opinion about the show, he is said to have replied, "I dare not trust myself to tell you. But if I could not give the people a better circus than that for their money, I’d eat my hat."

This apparently resulted in a wager of £100 from Sir Gilbert Greenhall, a fellow coaching enthusiast, egged on by R.G. Heaton, the Managing Director of Olympia. On a February evening of 1920, Bertram Mills sat down to dinner with his wife and his sons and announced to them, "I have just signed an agreement to run a circus at Olympia next winter." It came as something of a bombshell to the family; so far, Mills only had had contact with Olympia through the International Horse Show—although he was in close terms with its directors—and with the circus industry through his association with horses.

The Renovator Of The British Circus

The Olympia exhibition hall had opened in 1885 and had played host to a number of circuses before that of Wilkins and his partner, Young. The Great Hippodrome of Paris was staged at Olympia’s National Agricultural Hall in December 1886, and in the spring of 1889, Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show On Earth came to Olympia, and returned there for subsequent appearances in 1897. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West played Olympia for fifteen weeks in 1902/1903, and shortly before World War I broke out, impresario Charles B. Cochran had staged Hagenbeck’s Wonder Zoo and Circus, from Germany, in the winter of 1913/1914. Cochran had already had a circus and "Fun City" there in 1906. All were prestigious shows, hard to follow.

In order to win his wager, Mills, who had met John Ringling at the New York Horse Show, quickly arranged for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus to come to England for the 1920/1921 winter season: This was, after all, the biggest circus in the world returning to London after a long hiatus! Unfortunately, John Ringling was unable to arrange shipping space for such a huge undertaking so soon after the Great War. He had to ask Mills for cancellation of the contract, adding, "Let me know what I owe you." Mills, in typically decisive style, replied, "You owe me nothing; I will produce my own show."

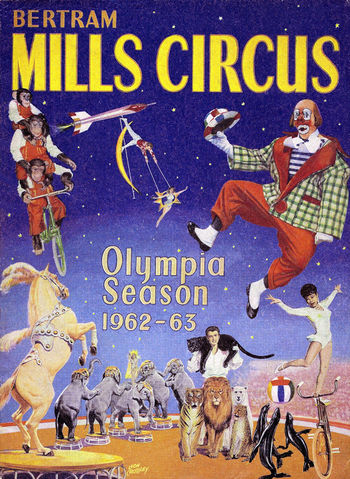

Thus, with a contract with Olympia’s management to honour, Bertram Mills became almost a reluctant showman and set about finding acts and producing his first show, The Great International Circus, organised by Bertram W. Mills, which was to take place from December 17, 1920 to January 24, 1921.This first production was a huge success, lauded by the press as "the best show in London for many years" and the "Great Circus Revival," and it even made a small profit. Eventually, Mr. Mills never had to sit down for a meal off his shiny top hat, and the show that became known as Bertram Mills Circus became the toast of London until it finally closed in 1967.

Mills brought the circus industry out of a slough period and placed it on a high pinnacle again. He did this by attracting the great and the good and famous to his shows. He introduced grand opening day luncheons attended by hundreds of leading figures of the country—people who, up to that time, had maybe thought the circus beneath their dignity. He sent invitations to the luncheons to those he thought were "the right people."

A close friend, the Earl of Lonsdale, became honorary president of the circus in 1922, presiding at the luncheons, which were also duly attended by the Lord Mayor of London and by title folks and members of the Parliament, making these events an annual function of considerable importance. One year, the total number of guests who sat down to the lunch preceding the opening performance was 1,493. The leaders of industry, the arts and the press joined the peerage, bishops, baronets and knights in vying for invitations.

In this way, and by the quality of the circuses he staged at Olympia and in the provinces, Bertram Mills raised the status of the circus to heights hitherto undreamed of. Booking the cream of talent available from Europe and America, and cutting acts ruthlessly to show just their best routines, Mills gained a reputation equal to none in Europe. His circus became known as "The Blue Ribbon Circus," "The Quality Show," and the one in which artistes aspired to appear.

Bertram Mills Circus Hits The Road

Bertram W. Mills was fortunate to have two well-educated sons, Cyril and Bernard Mills, who were able and willing to join him in his circus enterprise, and who carried it on in his style after his death—until rising costs signalled the end in 1967.

There was not enough to do in promoting the short Christmas season in London to occupy three full-time directors, so in 1930, Bertram Mills launched a tenting circus, which was run on a day-to-day basis by his sons. It was also run along the rules laid down by the father—namely that the show on the road would be of a standard and quality equal to that of the Olympia show, and run in a strictly business-like fashion.

The tenting show operated from 1930 to 1964, barring the years of the Second World War. After the death of their father in 1938, Cyril and Bernard Mills continued to run the company to the template he had established, retaining the tenets of "The Quality Show." Bertram Mills told his sons, "Just because we’re going cut as a travelling circus, I will not have you living like gypsies. The same must be true of every act with which we travel. The Mills Circus will perform like professionals and live like gentlemen."Prior to launching the Bertram Mills Circus as a tenting show, Bertram Mills and his sons entered into a one-season cooperation with the showman and illusionist Harry Cameron, better known as The Great Carmo, from which they learned much about the pitfalls of operating a tenting circus. When they launched their own show in 1930 under the Mills title, they used the tried and tested elements of the best German shows, like Circus Sarrasani.

Their first big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), seating 3,000, came from the German firm of Stromeyer, which for many years dominated the tent-making market. The seating system also came from Germany—the country that had developed at the time the most advanced and innovative systems for tenting shows. Starting in 1933, like most German circuses, the Bertram Mills Circus would also move by rail, the only British circus to do so.

The Mills Circus, which had for a decade appeared with huge success each winter in London, was now to appear throughout the provinces, dividing the country into a three-year cycle—and thus being able to retain acts under contract for three years. Artistes of the highest calibre, who had delighted London audiences, were engaged for the touring version, and for the first time, it was thought necessary to establish the show’s own stud of horses and ponies, which were trained by the Polish maestro Czeslaw Mroczkowsky.

In subsequent years, "House trainers" were engaged to present Mills’ own elephants, wild animals and other acts—and by this evolved a pattern by which Mills could feature its own animal resources on tour, at Olympia, and in the circuses of other promoters at home and abroad.

Insisting on a top level of presentation and cleanliness for his tenting circus, Mills introduced to provincial audiences the cream of world circus talent, including the wild animal acts of the Cossmy family; The Great Wallendas’ high wireA tight, heavy metallic cable placed high above the ground, on which wire walkers do crossings and various acrobatic exercises. Not to be confused with a tight wire. act; Leinert, the Human Cannonball; Rudolf Matthies and his tigers; Power’s Wonder Elephants; Kannan Bombayo’s bounding rope act; the female fakir Koringa and the American clown Emmett Kelly—whilst also nurturing native talent like Priscilla Kayes and the outstanding jockeyClassic equestrian act in which the participants ride standing in various attitudes on a galoping horse, perform various jumps while on the horse, and from the ground to the horse, and perform classic horse-vaulting exercises. troupe of the Baker family.

Bertram Mills’ Legacy

Mills’ sons, Cyril and Bernard, were stunned by the death of their father on April 16, 1938, but as he would have wished, the circus had its premiere that day in Luton. Many circus folks attended Bertram Mills’ funeral on April 19, while 200 members of the Mills Circus staff attended a memorial service the same afternoon, held under the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) at Luton, with the circus band accompanying the hymns. No performances were given on the day of the funeral, but they were resumed the following day.

Thereupon, Cyril and Bernard Mills took over their father’s enterprise and, in July 1938, set up a new company, Cyril and Bernard Mills Ltd. (of which their mother was also a director), to run the tenting show and the annual winter circus at Olympia. Bertram W. Mills bequeathed all his property to his widow. He left £146,528 (£100,528 net), a considerable sum for that time, with death duties of £20,957. His sons continued to operate the touring circus and the circus at Olympia until the advent of the Second World War. They closed for the duration, reopening in 1946.During the nearly twenty years in which he operated at Olympia in London, Bertram Mills brought circus fans many of the era’s greatest attractions. Among many others, one might select such circus luminaries as the Siegrist-Silbon Troupe of aerialists; juggling legend Enrico Rastelli; the Flying Codonas; the illustrious aerial transvestite Barbette; Con Colleano, "The Wizard of the Wire;" the Flying Concellos; Katie Sandwina, "The World’s Strongest Woman;" Schaeffer’s thirty Midgets; and the contortionist on trapeze Albert Powell.

On the animal side, there were the high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) riders Baptista Schreiber, Roberto de Vasconcellos, Jean and Marcelle Houcke, and Fredy Knie; the equestrians May Wirth and the Wirth family; Mabel Stark with her "parachute horse," Jupiter; The Hanneford Family; Alphonse Rancy’s horses; the Cirkus Orlando’s horses; and the huge stud of horses and ponies of Cirkus Schumann. There were also Captain Alfred Schneider’s seventy lions, Koringa and her crocodiles, and Tuffy the wire-walking lion.

The clowns were also very well represented with, notably, Pimpo, the star clown of Sanger’s Circus; Charlie Rivel; the Bronetts, Swedish clowns who were the Northern European rivals of the Fratellinis; and clowns who became associated with Bertram Mills Circus, like Doodles, Whimsical Walker, and Coco (Nikolai Polakovs). These are just a handful of the top-class attractions he brought to England.

At Olympia, the circus was also organised around a huge funfair, or carnival, with attractions that have included the Plate-Lipped Women from the Congo and the Giraffe-Necked Women from Upper Burma—who were also exhibited with enormous success by Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in the United States—and Ringling’s famous gorilla, Gargantua. Ringling’s sideshow manager, Clyde Ingalls, ran the funfair for several winters. In the first London seasons, too, Ringling’s legendary musical director, Merle Evans, directed the Mills’ band.

In her autobiography, Life’s A Circus (1930), Lady Eleanor Smith noted that Bertram Mills "was the first person to cut numbers to their bare essential. That is to say he would book an act accustomed to work for twenty minutes and cut it down to five. Nothing dragged, and nothing was allowed to become boring, but it may well be imagined with what fury certain artistes greeted this innovation. The Guv’nor was indifferent. He pared every moment down to its ultimate moment of thrill, surprise, grace or comedy. The padding didn’t interest him."

Bertram Mills’ Five Principles

Nearly a century following the conception of Bertram W. Mills’ original circus, it may be hard to readers to comprehend the enormous social and entertainment impact this show brought to Great Britain. In creating this great show from what appears to have been a simple and naïve wager, Bertram Mills brought five major principles, which he applied ruthlessly to his enterprise.

The first was to strive for quality in whatever he did, to seek out the most polished and perfect acts in every category, and to present only the best aspects of those acts—this being his second principle. Then, at all costs, he sought to attract, host and convert the most influential people to the cause of the circus, having starting his show at a time with this industry was at a particularly low ebb in Great Britain. Fourthly, he didn’t hesitate to promote individual acts or performers as stars of the show, and fifthly, he used and developed the emerging energy of public relations and targeted advertising.

By creating a demand in "the great and the good" of the nation to see his circus, Bertram Mills raised the social status of the circus in general. Undoubtedly, the most significant development in his success was the patronage of Royalty to Bertram Mills Circus. This began in 1926, when the Prince of Wales (the future Duke of Windsor) quietly attended a performance at Olympia, unannounced.

The Prince’s interest in the circus was further developed by visiting the show’s winter quarters at Ascot, near Windsor Castle, to observe the animal training sessions. A private box was installed for this purpose, since the Prince’s companion for these visits was his lover and future wife, Mrs. Wallis Simpson.

This led to an association with the Royal Family that, in hindsight, might appear simply breathtaking. There would be a further fifty-nine high profile visits by members of the Royal Family in subsequent years. The Queen went as a child, became a firm fan of the circus, and later graced Olympia with a series of well-publicised Royal Performances for her favourite charities.

Bertram Mills was buried in the St. Giles churchyard at Chalfont St. Giles; his grave is a simple one, and doesn't mention anything of his extraordinary life—beside the fact that he was "beloved." Perhaps Bertram Mills' true epitaph was written by the Duchess of Kent, who with the Duke brought their young son, Prince George, to the last Olympia season in 1967. She said to Cyril Mills: "He really is too young, but this is your last circus and I didn’t want him to grow up without having seen it."

Bertram W. Mills’ circus was a truly remarkable institution, more than just a circus. As a chronicler summed it up, "In the days of the shoddy and the pseudo, it restated the values of human ability, true artistry and high endeavour." For this reason alone, the name of Bertram W. Mills is still revered in Great Britain.

See Also

- Circuses: Bertram Mills Circus

- Biography: Cyril Mills

Suggested Reading

- A. Stanley Williamson, On The Road With Bertram Mills (London, Chatto & Windus, 1937)

- Robert Aylwin, The Bertram Mills Book Of The Circus (London, Naldrett, 1954)

- Cyril Bertram Mills, Bertram Mills Circus — Its Story (London, Hutchinson, 1967; paperback reprint published by Ashgrove Press, Bath, in 1983) — ISBN 0-906798-22-1

- David Jamieson, Bertram Mills — The Circus That Travelled By Train (Little Hormead, Aardvark Publishing, 1998) — ISBN 1-872904-11-4