Circus Nikulin

From Circopedia

The Circus On Tsvetnoy Boulevard

By Dominique Jando

Circus buildings with a long history have something magical. They seem haunted by the protective ghosts of the great star performers who, over the years, have graced their ring. The world’s oldest extant circus building, Paris’s Cirque d’Hiver, where Jules Léotard originated the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) in 1859, is one of them. The glorious Circus Ciniselli in St. Petersburg, Russia’s oldest circus, is another one. And in Moscow, there is Circus Nikulin—"the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard."

The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard: Three distinct circus buildings, actually, have been known under that name. The three buildings have occupied the exact same place, 13 Tsvetnoy Boulevard, with no longer interruption than the time needed for their reconstruction. Yet, for the Muscovites, they have been one and the same—their circus, just wearing different coats.

Before the Soviet revolution, Russian circus history was principally written in St. Petersburg, the Russian Empire’s capital, and began when the French equestrian Jacques Tourniaire built the Cirque Olympique, Russia’s first circus, in 1827 near the Fontanka canal, on the spot where Circus Ciniselli (which is extant) would be erected half a century later. Tourniaire had performed in Moscow in 1826, but this was in the private manège of the Pashkov House, which today houses the Russian State Library—with its magnificent manège refurbished as the main reading roon.

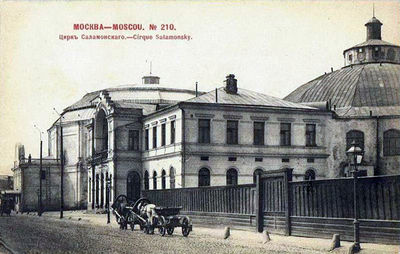

Moscow’s first circus was a wooden structure erected in the Niskuchnye Gardens in 1830, which lasted three summer seasons. The second circus, Laura Bassin’s, was built in 1853 and lasted only two seasons. The third was the circus the Austrian-Hungarian equestrian Carl Magnus Hinné had built in 1869 as the Moscow branch of his St. Petersburg flagship circus; it would remain active, under various managements, until 1896. Then, in 1880, Albert Salamonsky (1839-1913), a brilliant German equestrian and director, built a brand new circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard.

Circus Salamonsky

Hinné had hired Salamonsky in 1869 to perform with his horses and his company in the Austrian-Hungarian director’s new building in Moscow. Salamonsky, who was an accomplished high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) rider, and an outstanding trainer of "liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip." acts, had obtained a considerable success with Hinné, and he began afterward to tour regularly in Russia. In 1879, he built a circus in Odessa, but a shrewd businessman, he knew that the place to make real money was Moscow—the Empire’s wealthy merchant center—where Hinné’s circus, which was mostly harboring foreign touring companies, had no true identity of its own.Albert Salamonsky found a perfect location on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (literally, the "colorful boulevard," so called because of its large dividing promenade adorned with gardens). Tsvetnoy Boulevard led to the Ring, the first circular boulevard that defines downtown Moscow today, but which was at the time marking the city limits. Tsvetnoy Boulevard was a favorite destination for Muscovites, who found there many cafés and distractions, including fairground attractions such as traveling menageries and theaters, to which the boulevard offered ample space to install their balagans(Russian) Fairground booths or theaters..

In May 1880, Moscow’s newspapers announced that Albert Salamonsky had begun the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of a new circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, near the Panorama—a circular building where a 360º landcape trompe l’œil painting was exhibited, a popular urban attraction(Russian) A circus act that can occupy up to the entire second half of a circus performance. in the nineteenth century. The circus, designed by the architect August Weber and financed by Aleksandr Danilov, a gold mining entrepreneur and circus enthusiast, was completed on October 12, and opened to the public eight days later.

An imposing stone structure, it was said to accommodate 4,000 spectators, a largely inflated number since most of them would have had to stand in a vast promenade located at the periphery of the house, behind the last row of seats. It was a circular circus (or, more precisely, a twelve-sided polygon), on the model popularized by Paris’s Cirque des Champs-Elysées: it didn’t have, added to the ring, the classical theater stage that had been the norm since the original circuses of Philip Astley and Charles Hughes had appeared in the eighteenth century.

The circus stables, which could accommodate one hundred horses, were open to the public during the intermission, and, adjacent to the majestic entrance to the building, was a café that would become, over the years, Salamonsky’s favorite hangout—to the point when his wife, the famous equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. Lina Schwarz, would have to take over the daily administration of the circus which her husband had gradually become unable to assume.

Despite his devastating weakness for the bottle, Albert Salamonsky was a remarkable artist and a great artistic director, and his new Moscow circus quickly acquired an excellent reputation all over Europe. His horsemanship was greatly admired in the equestrian world, and he trained a host of good equestrians, among whom Eugen Marder-Salamonsky (pupils at the time often adopted their mentor’s name) who, in 1882, presented an equestrian carousel of 32 horses in the ring of Circus Salmonsky.

Circus Salamonsky, which Muscovites began to refer as the "Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard," had no serious competition from what was now known as the "old circus Hinné"—which had passed under the management of Gaetano Ciniselli—whose image was that of a circus house for rent to whoever paid the fee, and the branch of a St. Petersburg institution to boot. Circus Salamonsky had no trouble appearing as the genuine Moscow circus.

The Nikitins’ Competition

In 1886, the first truly Russian circus directors, the Nikitin brothers, bought the Panorama adjacent to Circus Salamonsky, and transformed it into a circus! Needless to say, Albert Salamonsky was not amused: at the end of the season, he bought back the Panorama building at a price (30,000 roubles) that gave a substantial profit to the Nikitin brothers, and he transformed it into a manège where he rehearsed his horses in public and gave riding lessons. The transaction included a promise signed by Dmitri Nikitin that the brothers wouldn’t compete with Salamonsky in Moscow. (Salamonsky later sold the Panorama, whose building is extant—albeit not without many substantial transformations over the years—and houses today the Mir Theater.)The Nikitins returned to Moscow in 1888, and rented this time the old Circus Hinné. Salamonsky went to remind them of their signed promise, but the wily brothers argued that the letter of agreement had been signed by Dmitri Nikitin, who had left by then his brothers to create his own enterprise, and consequently, they (Piotr and Akim Nikitin) were not bound by the agreement. Luckily for Salamonsky, the business at the old circus didn’t prove satisfactory, and the Nikitins decided not to renew their lease at the end of the season.

The Nikitins built several circuses in Russia, and established their seat in Tiflis (today Tbilisi, in Georgia). When their circus at Tiflis burnt down in 1911, Akim Nikitin (1843-1917), now alone at the helm of the family enterprise, decided to build his new flagship circus in Moscow. Moscow’s Circus Nikitin was erected that same year on Triomfalnaya Square and Bolshoi Sadoyava Street. By then, the old Circus Hinné had disappeared, and until 1919 (after the Soviet revolution), Circus Salamonsky would be in direct competition with the new Circus Nikitin.

At first, Circus Salamonsky was still perceived as Moscow’s aristocratic circus, a beacon of style, sophistication, and great equestrian tradition—in opposition to Circus Nikitin’s more populist image, with its weakness for spectacular stunt acts and water pantomimes (like the Nouveau Cirque in Paris, it had a ring that could be transformed into a swimming pool). But Albert Salamonsky died in 1913, and everything changed. According to Mikhail Bulgakov in his satiric novel, Heart of a Dog (1923), set in the early years of the new Soviet regime, Circus Salamonsky and Circus Nikitin eventually reached a comparable level of vulgarity…

The Soviet Era

Akim Nikitin died in April 1917, six months before the Bolshevik revolution began. His son, Nikolai (1887-1963), a talented juggler on horseback, succeeded him. Already in 1914, feeling the early winds of the Revolution, Circus Salamonsky’s artists and personnel had elected their own director, Yury Radunsky. Then, in 1919, all the Russian circuses, including Moscow’s two circuses, were nationalized like everything else.

The nationalization of the circuses resulted in a massive exodus of a vast majority of the foreign artists and directors who had made the success of the Russian circus. Even Nikolai Nikitin, deprived of the circuses his father had built, went to perform his juggling-on-horseback act in Italy. (He would return to Russia, as a simple circus artist, in 1922.)A rather confuse period followed, during which various Revolutionary Committees and groups of intellectuals tried to define a politically-correct circus devoted to the elevation of the proletarian masses. It culminated in the production, at the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, of an experimental, multi-disciplinary spectacle directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky, Political Carousel, which was a complete fiasco.

Finally, in 1921, the Soviet Committee for the Arts asked Williams Truzzi (1889-1931) to take over the artistic management of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. The Italian Truzzi family had been prominent circus artists and impresarios in Tzarist Russia, and had long settled in Voronezh, where they had built their flagship circus. Born in Russia, Williams was a Soviet citizen, and like most members of his family, he had chosen to stay after the Revolution. A true circus professional, Williams Truzzi was also given the artistic management of the former Circus Ciniselli in Leningrad (the old St. Peterburg), and of the former Circus Nikitin in Moscow.

In 1925, the old apartment of Albert Salamonsky, which was located within the circus building (in order to watch over his horses, there was always an apartment for the Director in the circus buildings of that era), was taken over by the staff of Tsirk (Circus), the first Russian official trade magazine for the circus. (Tsirk would continue its publication until the early 1990s, a few years after the end of the Soviet regime.)

In 1926, Truzzi closed the old Circus Nikitin: The penury of highly skilled circus artists in the new USSR didn’t make possible to run two circuses of equal quality in the new capital. This situation would lead, three years later, to the creation of Moscow’s State College for Circus and Variety Arts (1929), the first modern circus school. (The very first circus school, in fact, was created in St. Petersburg by Tzar Nicholas I in 1847.) Circus Nikitin was transformed into a theater—still extant—the Theatre of Satire. Meanwhile, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became the flagship circus of the Soviet Union, and more than ever, Moscow’s very own circus.

The Committee for the Arts, however, was still overseeing the circus; under Truzzi’s management, which lasted until 1924, and afterwards, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard continued to present a stream of edifying political spectacles, including one written by Vladimir Mayakovsky, Moscow Burns (1930). Like most of the others, Moscow Burns had a rather icy reception. Nonetheless, the use of writers, directors, designers, choreographers, and musicians who were not originally involved with the circus arts, would have a significant and lasting impact on the Soviet circus.

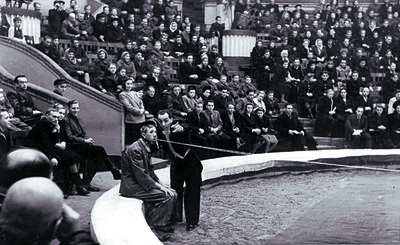

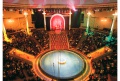

Williams Truzzi died unexpectedly, at age forty-two, in 1931. During his tenure in Moscow and then in St.Petersburg, he had shown that like any other performing art, circus worked better in the hands of professionals. At long last, in 1936, the Soviet circus was placed under the control of a specialized agency, the Circus Central Management (GosTsirk, replaced in 1957 by SoyuzGosTsirk, the Union of State Circuses). The very first action of the Central Management was to demolish most of the old Salamonsky building, and replace it with a circus more adapted to the needs of the times.The new circus, which opened in 1937, was officially named Moscow State Circus of the Order of Lenin, but to its Muscovite audiences, it remained the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. Its façade had lost the aristocratic looks of the old Circus Salamonsky, but its house had retained a classic elegance, and with 1,500 seats (gone were the promenade and the uncomfortable benches of the popular section), it had an atmosphere of warmth and intimacy. Only the best acts of the land were invited to perform at the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard—and to Soviet circus artists, playing there quickly become a badge of artistic achievement.

Toward the end of WWII, in February 1944, the Circus hosted the first All-Union Circus Competition, a festival of the new crop of acts that had graduated from the Circus College in the previous years. This would become an important annual event: The laureates were assured of a contract on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, and starting in 1956, they could also be invited on international tours of the so-called Moscow Circus—indeed a much coveted privilege under the reclusive Soviet regime.

The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard also hosted foreign circus productions, usually coming from countries behind the Iron Curtain, but it also presented two official French circus companies in the winters of 1958-1959 and 1960-1961, and an American Circus program made of star acts from the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus’s roster in 1964. These rare and short windows half open on the West obtained of course a huge success with Russian audiences.

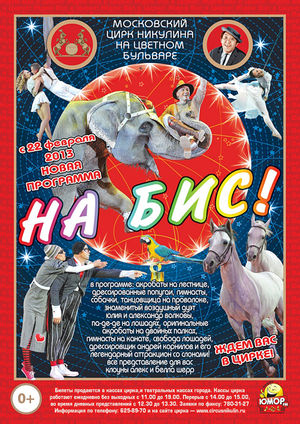

Circus Nikulin on Tsvetnoy Boulevard

After the War, while new circuses were mushrooming all over the Soviet Union, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard was the circus of reference, the place where each of the 5,000 Soviet circus performers dreamed of playing. This was the time, too, when the Soviet circus reached its artistic peak, and for the next forty years would gradually change the image of circus arts the world over. The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard became the epicenter of this renaissance, until its preeminence was contested by the new, state-of-the-art circus that Leonid Brezhnev had had built at Vernadsky Avenue, on Lenin Hill, near Moscow University—and which is known today as Moscow’s Bolshoi Circus.If the new circus’s amenities were indeed impressive, and the artistic possibilities they offered were (and remain) unmatched, it didn’t have, with its 3,500 seats, the same warmth and intimacy as the "old circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard—neither did it have its rich history and tradition. Furthermore, the new circus was located far from the center of Moscow: The "old circus" (as it became known) remained Moscow’s most popular circus, and it never lost its place in the heart of the Muscovite audience.

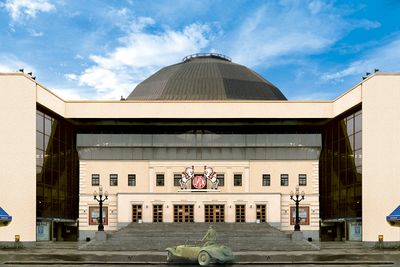

But the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard didn’t stay "old" for long. In 1982, its management was given to the most famous and beloved star of the Russian circus, the great clown (and movie actor) Yury Nikulin (1921-1997). Under his watch, the circus gave an emotional last performance on August 13, 1985, before being torn down. A sign of the changes taking place in the Soviet Union, its reconstruction was entrusted to a Finnish company named "Polar". Nikolai Ryzhkov, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, helped Nikulin raise the money.

Four years later, on September 29, 1989, a brand new circus opened its doors—and to everybody’s relief, one still could see the old façade, even though it was framed within a giant modern glass front. Another sign of continuity was the house, which resembled the old one, with its characteristic columns and color scheme—and had retained its warmth, although it had been significantly enlarged, with a seating capacity of 2,000.

Of course, this was only the visible part of the iceberg: The new circus is in fact a completely different building. To begin with, its cupola has been considerably elevated, allowing the presentation of the new giant flying acts that had been, until then, the exclusive domain of the Bolshoi Circus. The stage, above the artists’ entrance, has been expanded and properly equipped, and a three-part, telescopic luminous staircase can rely it to the ring. The ring curb(American. French: Banquette. Russian: Barrier) The circular barrier that defines the ring, and separates it from the audience. can be lowered into the floor for non-circus events, or can be replaced with a circular lighting ramp.The vast area backstage contains a rehearsal space, with a full circus ring and the possibility to accommodate major flying acts; it can be isolated from the backstage area during rehearsals. It is in this rehearsal space that, in the 1990s, the legendary act director Valentin Gneushev had his Studio. There is also considerable space for animals, dressing rooms, offices, and workshops, all with modern and practical design and construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.". A vast two-level foyer occupies the space behind the glass front on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, and shops, leased to outside businesses, occupy the street level on each side of the building—including a café, which would have been to the taste of the old Albert Salamonsky. The place is a far cry from the heavy, Soviet-style construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." of the Bolshoi Circus, which may now be seen as the "old circus."

In 1987, Yury Nikulin had passed the general management of the new circus on to his son, Maxim, a former journalist who has grown up within the circus world. When the Soviet regime fell apart, Maxim Nikulin negotiated the independence of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard from RosGosTsirk (the former SoyuzGosTsirk), the Russian central circus organization.

After the death of Yury Nikulin in 1997, the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard was renamed Circus Nikulin. The great clown is remembered with a bronze monument, which represents him in his clown costume, getting out of his little roadster badly parked in front of the circus—a familiar image dating back to the time when Nikulin used to rush from the MosFilm studios, where he was shooting films in the afternoon, to the circus to appear in the ring in the evening. On this whimsical sculpture, as well as on a smaller bust of the beloved clown in the foyer, Muscovites visiting the circus often leave a small bouquet of flowers.

Suggested Reading

- Yury Dmitriev, My Old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard (Moscow, Lazur, 2000) — In Russian — ISBN 5-85806-028-5