The Codonas

From Circopedia

Flying Trapeze

By Dominique Jando

The Codonas (and Alfredo Codona in particular) were conceivably, in terms of international fame, the greatest circus stars of the first half of the twentieth century. They owe their distinctive place in circus history to the exceptional talent of Alfredo Codona, but also to the dramatic ending of his career, and subsequently, the tragic conclusion of his life. Not only was The Codonas’ act recorded on film (in E.A. Dupont’s Varieté in 1925), but they were also the subjects of an Academy Award-nominated documentary, Jack Cummings’s Swing High (1932), a romanticized biopic, A.M. Rabenalt’s Die drei Codonas (1940)—a very rare occurrence for circus artists—and two romanticized biographies.

Eduardo Codona

Alfredo (1893-1937) and Abelardo ("Lalo," 1895-1951) Codona were born into a circus family. Their grandfather, Henry, came from a long line of Scottish showmen of Swiss-Italian descent. Francesco (Frank) Codoni (1765-1849), the dynasty's founder, settled in Scotland in the nineteenth century; he was a fairground showman, and illiterate—which led the family's name to be registered under a great variety of spellings over the years: Cardoni, Cardownie, Cardone, Codone, Candone, and Codona, which eventually stuck in the 1870s. Henry Codona married a French woman, Victorine Régnier (1841-1924), with whom he had two children, Enrique and Eduardo, who was born in Mexico on September 21, 1859. (Enrique and Eduardo also had a half-brother, William). When and for which purpose Henry and Victorine immigrated to Mexico is not known.

In any event, Eduardo Codona (1859-1934) became a Mexican circus performer and entrepreneur. In 1883, he married the fourteen-year-old Hortense (Hortensia) Buislay (1869-1931), a trapezist who hailed from an old French circus family of "acrobats, pantomimists, and gymnasts" (i.e., aerialists). The enterprising Buislays had come to Mexico where, in 1869 (the year of Hortense’s birth), they created with Ricardo Bell the Circo Océano, and rented Giuseppe Chiarini’s circus building in Mexico City before touring the country for some time. Like Chiarini, in whose circus company they had previously traveled around the world, the Buislay family had settled in San Francisco, in the United States.

By 1888, Eduardo Codona had formed his own traveling company. He had with him a Comanche Indian who wrestled a bear named Samson, and Hortense partnered with a girl billed as Matilde in a trapeze act. Eduardo worked as a tumbler and in a flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) act "à la Léotard"—the creator of the genre, who had been the toast of Europe and had even performed in New York in 1868. In essence this means that, like Léotard, Eduardo worked alone, leaping from trapeze to trapeze. Flying trapeze, in whatever form, proved to be a specialty to which Eduardo was particularly attracted.The Codonas’ children were born on the road, wherever their parents’ travels took them: Alfredo on September 7, 1893 in Hermosillo, in the state of Sonora, and Lalo on October 20, 1895 in Zitácuaro, Michoacán. They had an elder sister, Victoria (1890-1983), and three younger siblings, Joe, Hortense (1900-1987), and Rosa. Eduardo and Hortensia began training their children at an early age in a wide range of circus specialties, notably aerial acts and icarism(French: Jeux Icariens) Act performed by Icarists, in which one acrobat, lying on his back, juggles another acrobat with his feet. (Also: Risley Act)—which had been one of the Buislays’ areas of expertise. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Codonas, father and sons, had added to their large repertoire a Risley actAct performed by Icarists, in which one acrobat, lying on his back, juggles another acrobat with his feet. (Named after Richard Risley Carlisle, who developed this type of act.), as well as a triple horizontal bar act—the best possible introduction to the practice of flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze).

From the 1890s through 1905, the ever growing Codona family worked for various Mexican circuses. Then, in 1906, Eduardo, whose children had matured enough to provide him with talent and support, revived his own circus. It toured Northern Mexico until 1909 and ventured sometimes across the border in the neighboring southeastern American states—where a talent scout might have spotted it: Alfredo was hired to perform his single trapeze act with the Barnum & Bailey Circus for two seasons (1910-1911), while Victoria did her slack wireA Tight Wire, or Low Wire, kept slack, and generally used for juggling or balancing tricks. act in the same program.

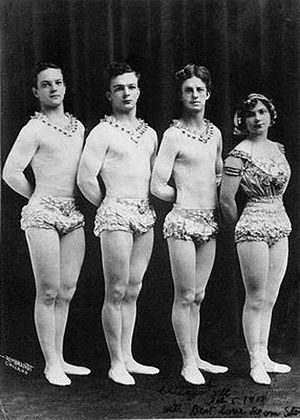

The Flying Codonas

When Alfredo returned to the family fold, Eduardo began to build a flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) act for him, working as his catcherIn an acrobatic or a flying act, the person whose role is to catch acrobats that have been propelled in the air. before training Lalo in that capacity. Alfredo quickly showed a taste and a natural ability for flying. He had also an innate grace: Another flying legend, Art Concello, once remarked that "If Alfredo had been run over by a truck, he’d have done it so gracefully that your first instinct might have been to applaud." The Flying Codonas made their first notable appearance in Australia, performing for three seasons (1913-1915) with the Wirth Circus, in an act that was composed of Alfredo and Lalo, and Ruth Farris and Steve Outch, two young Australian flyers. (Outch was already an experienced flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard)., and had worked before with the Flying Jordans, but Farris was probably there to provide the required "feminine element" to the act.)

At the end of 1915, the Codonas returned home with Steve Outch in tow. Alfredo and Lalo had gained by then a good flying experience, and the trio secured a contract for the 1916 season with the fourteen-person strong Siegrist-Silbon Troupe—whom Alfredo had met in 1910, when he was working on the Barnum & Bailey show. The Siegrist-Silbons, one of the best flying acts in the business at the time, had created a spectacular act that was performed with two flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) frames placed in a cross. It is in the Sigriest-Silbon Troupe that Alfredo met a young brunette who was, like him, a newcomer to the act, Cincinnati-born Clara Groves, née Curtin (1894-1972).Alfredo and Clara fell in love. Alfredo also realized that with Alfredo, Outch, and Clara as "the feminine element," he could rebuild his own act. Clara divorced her husband, Indian Groves (who was part of a casting act, The Valentinos), and the quatuor left the Siegrist-Silbons in the winter of 1917 to debut their brand new flying actAny aerial act in which an acrobat is propelled in the air from one point to another. at the popular Circo Pubillones in Havana, Cuba—where Alfredo and Clara also got married. The Codonas remained with Circo Pubillones until 1918. (They shared the bill with Alfred Court, who was still an acrobat then, and performed a perch pole act.) But the ambitious Alfredo was not satisfied just to have his own flying actAny aerial act in which an acrobat is propelled in the air from one point to another.; his new goal was to replicate Ernie Clarke’s exploit, the elusive triple somersault on the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze).

The British flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard). Ernest Clarke (1876-1941), with his brother Charles (1878-1951) as his catcherIn an acrobatic or a flying act, the person whose role is to catch acrobats that have been propelled in the air., was the star of The Clarkonians. The Clarkonians’ act was quite extraordinary in that it was just a two-person flying actAny aerial act in which an acrobat is propelled in the air from one point to another., with nobody on the return platform to help the flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard).. But Ernie Clarke was an outstanding flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard).: He did, among other tricks, a remarkable double somersault followed by a full twist to the catcherIn an acrobatic or a flying act, the person whose role is to catch acrobats that have been propelled in the air.! Ernie and Charles Clarke had secured the triple in 1910, while working with the Ringling Bros. Circus; but although they attempted it regularly in performance, they were not always successful. In time, the physical strain the trickAny specific exercise in a circus act. put on both flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard). and catcherIn an acrobatic or a flying act, the person whose role is to catch acrobats that have been propelled in the air. led Ernie Clarke to drop the triple from his repertoire. (It must be noted that he was already thirty-six years old when he first mastered the trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.!)

Hired for the 1919 season by the Sells-Floto Circus, Alfredo began to work in earnest on his triple somersault. Like Clarke, and like many triple somersaulters after himself, Alfredo went for it by trial and error, without the help of a longe(French, Russian) Safety line connected to a performer by a belt, going through a pulley, and held on the other end by an assistant, or a teacher. Also know as a ''mécanique'' (see this word)., collecting along the way an impressive number of falls to the net. It was not a very scientific approach, but it worked: It finally took Alfredo and Lalo Codona a few winter months to truly master the trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.. They presented it for the first time on April 3, 1920, for the opening of the new Sells-Floto season at the Chicago Coliseum. Alfredo’s early percentage of successful catches was nine out of ten—a remarkable consistency, especially if one considers that, beside his father, no one with a relevant experience had been there to coach him! But Alfredo was a natural flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard). who showed an amazing ease and grace in everything he did in the air—even though his style, always praised by his contemporaries, seems a little loose by today’s standards.

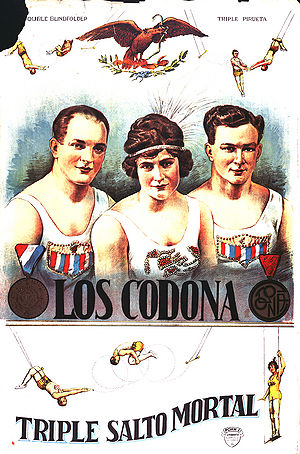

International Stars

The Codonas quickly became the talk of Circusdom. They moved up the following year (1920) to The Greatest Show On Earth—the newly combined Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey show. They were now a trio, Alfredo having a repertoire spectacular enough to do without a hired extra flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard).. They presented their triple for the first time at the show’s opening at the Chicago Coliseum. Good looking, charismatic, and extremely pleasant to watch (not to mention spectacular), Alfredo Codona became a true circus star, and The Codonas a much sought-after flying actAny aerial act in which an acrobat is propelled in the air from one point to another.. Star acts of the Ringling shows were often in demand in Europe during their winter break, and The Codonas were no exception indeed; they would work regularly on the Old Continent in major circuses and variety theaters.

Their first winter contract abroad was in 1922, at the Coliseu dos Recreios in Lisbon, Portugal—then one of Europe’s most prestigious resident circuses. The following winter (1923), they were in Barcelona, Spain, with the French circus Palisse—a luxurious traveling construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." that belonged to the clown Palisse, and which made prolonged stands in the cities it visited. (A little more than a decade later, Palisse’s construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." became the traveling unit of Paris’s Cirque Medrano.)They spent the year 1925 in Europe, first appearing at Circus Hagenbeck in Stellingen (near Hamburg). At Berlin’s famous Wintergarten, their act was filmed to be integrated in Ewald André Dupont’s silent movie, Varieté (1925), starring Emil Jannings (doubled in the air by Lalo), Lya de Putti (doubled by Clara), and Warwick Ward (doubled by Alfredo). The film, which was released in Great Britain as Variety, in France as Varietés, and in the United States as Vaudeville, was a huge international success. It told a tragic love story involving a trio of flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) stars, but although the Codonas had given the characters their credibility in the air, they were not given any on-screen credit.

Then the Codonas spent the summer at Circus Schumann in Copenhagen, Denmark. They ended the year starring in the Holiday Season (1925-1926) production of Europe’s most prestigious winter circus, Bertram Mills Circus, at the Olympia of Kensington in London—where they shared the bill with another Ringling star act, the incomparable equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback. May Wirth (whom Alfredo and Lalo had known in Australia), as well as with the great clown Charlie Rivel, and Alfred Schneider who presided over his 70 lions: Quite a program! At the end of the Mills engagement in January 1926, the Codonas set sail for Paris.

Gaston Desprez, the Director of Paris’s legendary Cirque d’Hiver, had offered them a contract to appear in the French capital from January 29 through February 11, 1926. At the Cirque d’Hiver, the birthplace of the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze), like everywhere else, The Codonas were a sensation; the savvy Parisian press loved them and the critics were not only impressed by Alfredo’s triple somersault, but also by his "elegance, precision and beauty." The Parisian audiences, who were very knowledgeable in matters of circus (there were still five circus buildings active at that time in the French capital, each presenting a new program every other week) agreed with the critics. Alfredo’s triple was now totally consistent; it was also unique, and Alfredo Codona was becoming a living legend.

Royal Wedding

Back to the United States, the Codonas returned to the Ringling show, where they had already been sharing the spotlight with another living legend, the tempestuous Queen of the Roman Rings, the diminutive and demanding Lillian Leitzel (1892-1931). Leitzel was the prima donna assoluta of the Ringling lot, a pampered center-ring star who was allowed to perform without competition from the otherwise ever-present yelling of the candy butchers, who had her own dressing-room tent pitched near the artists’ entrance to the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), and who had obtained her own suite on the Ringling train—a perk up till then reserved for the show’s high managerial brass. (Before Leitzel’s move, all the performers, stars or not, were simply allotted bunk beds in Pullman-style sleeping cars.)After an early solo career on the vaudeville stage, Leitzel had been contracted by the Ringlings in 1915 and featured in their Barnum & Bailey show. As Henry Ringling North later recognized, Lillian Leitzel owed her unique super-star status less to her talent than to her magnetic and domineering personality, both in the ring and out. She was not very pretty, with a large head on a small body (1.50m., or 4’9”), the shoulders of a wrestler and the waist of a wasp, but she compensated largely with her charm and her charismatic presence as a performer—and with a spectacular finale to her act that consisted of one hundred or more rotations of her body hanging by one arm from a hand-loop.

As fate would have it, the two brightest stars of the Ringling show, Alfredo Codona and Lillian Leitzel, fell in love. The story doesn’t tell if Leitzel went after the charismatic, talented, and handsome newly crowned trapeze star, or if Codona sought the Queen Of The Lot’s favors, but these two ambitious and egotistic personalities, both perfectionists consumed by their work, were either destined to attract each other, or to clash. As a matter of fact, they did both, for the ensuing union of the God and the Goddess of the Air would prove quite stormy.

On the other hand, Clara, who participated in the show’s aerial ballet in addition to the Codonas’ act, was injured during a rehearsal of the aerial ensemble at the beginning of the 1927 season. Not only was her aerial career on a hiatus (it actually ended), but also her marriage had fallen apart; she left the show and began a divorce procedure—a move strongly encouraged by Alfredo. (In spite of her divorce, Clara would keep her married name, Clara Codona, until her death in Cincinnati, Ohio on May 1, 1972.)

Enter Vera Bruce

If this new situation cleared the way for Alfredo and Lillian’s hitherto illicit relationship, Clara’s departure was a major problem for the Codonas’ trio, which found itself without a third member. Lillian suggested that they take a young Australian girl named Vera Bruce (1905-1937), who had come to the Ringling show to work with May Wirth’s equestrian troupe. Lillian and Vera had become good friends.A very attractive young girl, Vera Bruce was born in 1905 in Singapore, where her Australian parents worked with the British Clarke’s Circus, which was touring the Far East. Her father was the circus’s bandleader, and her mother, an aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc.. When she was in age to go to school, her parents had sent Vera as a boarder to the Convent of Mercy and Cabra in Adelaide, South Australia, to get an education; she remained with the Dominican nuns until the age of sixteen. Then, she returned to the family fold and to the circus, where she became an equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback., and finally went to America to be part of May Wirth’s act.

Although not an aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc. by trade, Bruce was a well-trained acrobat, and apparently a quick study: She was soon fully integrated into the Codonas’ act. In 1928, The Codonas went to Hollywood to shoot the flying sequences of F.W. Murnau’s movie, Four Devils (1928)—which told an improbable story (as usual in circus movies) involving four flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) artists, and starred Janet Gaynor and Charles Morton. Unfortunately, no copy of Four Devils has survived.

Clara’s divorce was finally granted and, on July 20, 1928, Alfredo Codona married Lillian Leitzel in Chicago, between performances of The Greatest Show On Earth. This was a royal wedding, the equivalent to the American circus world of what the marriage of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks was to Hollywood. Alfredo and Lillian also became an item professionally, and started working together in their winter engagements. As for the summer seasons, they both remained with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey for the rest of their respective careers.

Heartbreak

At some point in 1930, they performed in Monterrey, Mexico, with a Leitzel-Codona Circus that was meant to tour the Mexican Republic. The project was apparently aborted. The Codonas, and Lillian Leitzel, returned to Europe for the winter season of 1930-1931. For two months, in November and December, they were the stars of the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris. This was a long engagement by Cirque d’Hiver standards, but Desprez knew his audiences would flock to his circus to see Codona again, and he put some emphasis on Leitzel in his advertising, who became an extra draw. (Leitzel had already appeared at the Cirque d’Hiver, in December 1928—as “Miss Leitzel”—and although her spectacular finale made a definite impact on the audience, she had not yet reached in Europe the super-star status Alfredo was now giving her.)

The next engagement for The Codonas was Berlin’s Wintergarten. This time, Leitzel was not part of the package: instead, she had been signed for the Valencia, a combination of varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s., nightclub and restaurant located on Vesterbrogade in Copenhagen (behind the present Museum of Copenhagen). On Friday, February 13, 1931 tragedy struck: In the middle of her act, the swivel to which Lillian’s climbing rope was attached broke, and she fell nearly fifty feet to the ground. She was badly injured, and a telegram was sent to Alfredo in Berlin, telling him that she had been taken to a nearby hospital.Alfredo left Berlin immediately and rushed to Copenhagen with Nellie Pelikan, Lillian’s mother, who had come to Europe with the Codonas and had stayed in Berlin. When they saw her, Leitzel reassured them that she was going to be all right. Codona returned to the Wintergarten, just to learn that Leitzel, who had sustained spinal and other internal injuries, had passed away. Her mother had remained at her side. The date was February 15, 1931, just two days after her fall; Leitzel was thirty-nine.

Codona was devastated. A funeral service was held in Copenhagen on February 19, and Lillian’s body was cremated. His Berlin engagement over, Alfredo returned to the United States, where the news of Leitzel’s death had shocked the circus community and had been widely reported by the press. Leitzel’s ashes were finally buried at the Inglewood Park Cemetery in the Los Angeles, California, area on December 10, 1931—nearly one year after the tragedy. Codona had ordered a seventeen-foot white marble statue, titled Reunion, to an Italian sculptor. It represents an angel holding a woman in embrace, and was erected over the marker. Alfredo had this dedication engraved on the pedestal: "In everlasting memory of my beloved LEITZEL CODONA – Copenhagen Denmark – Feb. 15, 1931 – erected by her devoted husband ALFREDO CODONA".

According to some contemporaries, Alfredo Codona became reckless after Leitzel’s death, and the consistency of his triple somersault suffered from it. In any event, Alfredo went on to perform aerial stunts for Johnny Weissmuller in W.S. "Woody" Van Dyke’s Tarzan The Ape Man (1932), and for Alfred Santell's Polly of the Circus (1932)—in which Alfredo, in drag, doubles Marion Davies in a beautiful triple somersault filmed in slow motion—and the three Codonas were featured in Jack Cummings’s documentary, Swing High. In April 1932, during the Ringling show's Madison Square Garden engagement in New York, Alfredo missed a catch, fell into the net, and tore a shoulder muscle in the process. This was a minor incident, but the harbinger of things to come.

Meanwhile Alfredo began courting his partner, Vera Bruce—although some have said that it was Bruce who began courting Alfredo, even before Lillian’s death. Whatever the truth, it doesn’t seem illogical that the forlorn and handsome Alfredo and the pretty and strong-willed Vera, who spent most of their lives together, would eventually be attracted to one another. On September 18, 1932, Alfredo Codona and Vera Bruce were married in San Antonio, Texas, in a ceremony held in conjunction with the Circus Fans Association’s 1932 convention: It was indeed a huge affair, celebrated by the circus community as well as the circus aficionados. Yet it would prove more a marriage of convenience than a loving one.

Tragedies

Sadly, the flying career of Alfredo and Vera Codona as a married couple didn’t last long: Alfredo had another bad fall into the net on April 29, 1933 at Madison Square Garden, this time dislocating his shoulder and seriously injuring his arm. For a flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard)., a repeated shoulder injury can easily have tragic repercussions, and indeed such was the case: Alfredo’s flying days were over. He was replaced for the remaining of the season by a flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard). named Bert Doss, whose employment owed more to his availability at the right time than to the strength of his talents. The Flying Codonas left the center ring, which was given to the upcoming Flying Concellos, and they moved to a side ring.

For the 1934 and 1935 seasons, Alfredo was given a job as Performance Director on the Ringling-owned Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus. The Flying Codonas were also on the show, with a talented new flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard). named Clayton Behee (1912-1976), whom Alfredo was coaching for the triple. Yet Alfredo Codona, who had always craved the spotlight and had been used to being the center of attention, had a hard time watching his young protégé reap the applause in his place—even though Behee couldn’t (and didn’t) pretend to equal him. Codona became increasingly moody, and as a result, his marriage, which had not been built on a strong footing in the first place, took a turn for the worse.By the time Alfredo became Equestrian Director of the short-lived Tom Mix Circus and Wild West for the 1936 season, Vera had resumed her career as an equestrienneA female equestrian, or horse trainer, horse presenter, or acrobat on horseback., and had gone to work with her brother, Clarence Bruce, who had married one of the Riffenach Sisters. Vera was replaced in The Codonas' act by a young flyerAn acrobat that is propelled in the air, either in a flying act, or in an acrobatic act (i.e. teeterboard). named Rose Sullivan, who debuted with Lalo and Behee at Blackpool’s Tower Circus, in England. Clayton Behee was now turning the triple—but he would never have Alfredo’s amazing consistency, not to mention his exceptional grace.

Alfredo Codona didn’t return to the circus for the 1937 season; instead, he went to work in a garage owned by his sister Hortense’s husband, Charles Ferrante, in Long Beach, California, where the Codonas had settled. On June 28, Vera filed for divorce, on the grounds of cruelty. Codona pleaded no contest; the divorce was granted on July 1. On July 30, 1937, Alfredo Codona met Vera Bruce in the office of her attorney, James E. Pawson, in Long Beach to finalize details of the settlement. It was an amicable meeting. At some point, Alfredo told the lawyer that he wanted to be alone with his ex-wife. After Pawson had left the room, Codona draw a gun and shot Vera five times before turning the gun onto himself. Alfredo Codona died instantly; Vera died at Seaside Hospital in Long Beach the following day.

The tragedy, which was widely reported by the press with the inevitable dose of horrid flourish, didn’t make the front pages however: Alfredo Codona had been demoted by then to the rank of "former trapeze star." Sic gloria transit! According to his wishes, he was buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery on August 3, next to his second wife and greatest love, Lillian Leitzel. The funeral attracted a large crowd of circus colleagues and fans: In the circus world, Alfredo Codona was still royalty, the undisputed King of The Air. Vera Bruce-Codona was laid to rest at the Calvary Cemetery in East Los Angeles; the epitaph on her gravestone reads: "Peace at Last".

Epilogue

Needless to say, Lalo Codona was quite shaken by the events, and he considered retiring from performing altogether. But he had still some European contracts to fulfill, notably with Paris’s famed Cirque Medrano, where The Codonas were scheduled to appear in November for Medrano’s Jubilee program. During a practice session, Lalo hurt his shoulder and on opening night, November 12, his injury resulted in his missing his catch of Behee’s double somersault, and in more damage to his shoulder. When Lalo unlocked his legs to sit back on his trapeze, he lost his grip and fell into the net. He had dislocated his shoulder; Georges Loyal, Medrano’s ringmaster(American, English) The name given today to the old position of Equestrian Director, and by extension, to the presenter of the show., had to use a ladder to go up to the net and help Lalo down.

Lalo’s injuries actually ended his career, and with it, the legendary Flying Codonas act disappeared forever. Clayton Behee married Rose Sullivan, and went on with his own act, The Flying Behees. Lalo retired to California, where he went to work as a mechanic in his brother-in-law’s garage in Long Beach, and continued to do sporadic stunt work in Hollywood. He passed away on October 12, 1951, and was buried near Alfredo at Inglewood Park Cemetery.

Suggested Reading

- Joachim Brenner, Die drei Codonas (Berlin, A. Limbach, 1940)

- Alfons Zech, Die ganz grosse Nummer: Die 3 Codonas, Artistenschicksale (Heidenau bei Dresden, Vertagshaus Freya, 1940)

- Dean Jensen, Queen of the Air — A True Story of Love & Tragedy at the Circus (New York, Crown Publishers, 2013) — ISBN 978-0-307-98656-6

See Also

- Video: The Codonas at the Wintergarten, Berlin, 1925.

- Video: Swing High, featuring The Codonas, MGM documentary (1932)