Cirkus Kludsky

From Circopedia

By Pavel Vaculík

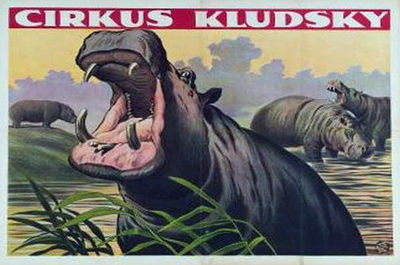

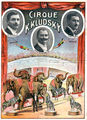

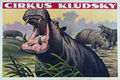

Cirkus Kludský, the most famous Czech circus and one of Europe’s largest ever, was at its peak a colossal enterprise traveling with an 86 x 54 meters (approximately 280 x 178 feet) three-ring, four-pole big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) that could seat 10,000 spectators. Its menagerie included a herd of 25 elephants, 160 horses, 74 wild animals (lions, tigers, leopards, etc.), and a vast assortment of exotic animals, among which three giraffes and a hippopotamus—an ensemble advertised at some 700 heads. Cirkus Kludský boasted two hundred performers from thirty-five nations, including two large bands, and two hundred wagons traveling by train were used to transport the circus equipment and house the personnel.

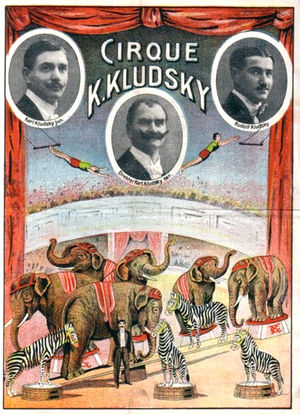

In 1929, when Cirkus Kludsky was invited to perform in Rome, Italy, for a run of fifty-two days, more than 600,000 spectators attended its performances. This gigantic organization belonged to the Czech Kludský family, and had been created before WWI by Karel Kludský (Carl Kludsky, as he became known in the West-European circus business). From humble beginnings, Karel Kludský had managed to build one of the biggest traveling circuses in Europe, which was subsequently continued and improved by his sons.

The Kludský Dynasty

According to family lore, the founder of the Kludský Dynasty was an adjutant to Jan Sobiesky (1629-1696), the Polish King who saved Vienna from the Turkish invasion in 1683. (The Czech Kingdom—or Kingdom of Bohemia—was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.) Whether the legend is true or not, the Kludskýs eventually became a family of traveling entertainers.

The Ottoman Empire had remained at odds with the Austro-Hungarian Empire and other Western European countries until its defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, and its ensuing rapid decline. Therefore, traveling entertainers from the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and the Holy Roman Empire in general) were not authorized to perform farther than Constantinople (today’s Istanbul). The first member of the Kludský dynasty who demonstrably obtained this authorization was Josef Kludský, from the village of Strážovice in South Bohemia, in 1789.

He was followed in 1820 by another Josef Kludský—this one from Mačice, near Bukovník, in the Sušice Region—who ran a mechanical theater and organized firework displays. A third Josef Kludský, from Bavorov, in the Strakonice District, tagged on; since 1846, he had traveled with his ropewalking troupe and a carousel. These three Josef Kludskýs were related, and all lived in the South Bohemian region of the Czech Kingdom. The Kludský family was large and widespread; over the years other members of the family ran traveling menageries, carousels, cinematographs, acrobatic troupes, and various traveling entertainments.The founder of the circus dynasty itself is considered to be Antonín Václav Kludský (1826-1895) of Bukovník, a traveling puppeteer and, later, the owner of carousels and a menagerie. He and his wife Maria (1832-1909) had twenty children, all boys—several of whom eventually became circus owners. Antonín had been granted a puppeteer license in 1852; he later bought a carousel and, in 1874, he acquired the famous Kreutsberg Menagerie of Leipzig, after the death of its owner, Gottlieb Kreutzberg, who had been killed by his tigers. The so-formed Kludský menagerie became the Czech Kingdom’s largest (as reflected by contemporary posters).

The menagerie was very successful, and in time, Antonín passed its actual management onto his elder son, Antonín Junior (1855?-1891), who became the principal shareholder of a combine whose ownership was divided between the Kludský brothers. Now a thriving entrepreneur, Antonín Senior had sent his other sons to school or encouraged them to find other lines of employment. One of them, Karel, was destined to become a priest and went to study theology in Hradec Králové.

There was much infighting between the brothers over financial matters however, and in 1886, his father withdrew Karel from the seminary to take part in the leadership of the business. Karel was only twenty-two. Sadly in 1891, Antonín Junior was killed on his wedding day by a lion called Menelik. Old Antonín was devastated, and closed his menagerie temporarily. He died four years later, in 1895. (He and his wife, Maria, are buried in Pilsen.) Karel decided to take over the menagerie, and sold the carrousels and other business assets in order to pay off his brothers. He was now sole in charge of the Kludský menagerie.

Karel Kludský I (1864-1927)

Born December 17, 1864 in the small village of Bukovník, near Sušice in the Šumava region, Karel Kludský is the true founder of Cirkus Kludský. It is he who transformed the menagerie into a circus, and led it to European prominence. The key to his success was a fearless entrepreneurial spirit and his will to try innovations in his approaches to performance and animal training.One of his most specific and long-lasting legacies, however, was his hiring circus workers in his native Šumava region (the Bohemian Forest, located at the border of the Czech Kingdom with Bavaria and Austria). They were hard-working people, lumberjacks for the most part, who proved particularly apt at tent rigging, and often doubled as excellent circus musicians. These qualities soon attracted other major European circuses such as Krone, Sarrasani, Gleich, Hagenbeck and others, which followed Kludský’s model. It was these Bohemian workers who originated the term tcheco(Europe) A tent crew or circus worker. Before WWII, the best of them usually came from the Bohemia region in Czechoslovakia. (Somtimes spelled "Tcheko") which, in European circus lingo, means "circus worker."

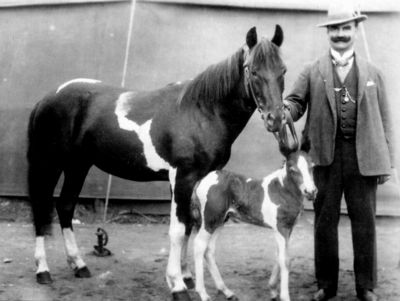

In 1902, Karel acquired the horses of Circus Wulff, whose owner, Eduard Wulff, had filed for bankruptcy, and he added a full-fledged circus to his traveling menagerie with the additional purchase of the German circus Enders’s equipment. Like many traveling menagerie owners who converted to circus around the same period (Carl Krone and Hans Stosch-Sarrasani among them), Karel’s inspiration was the giant American circus Barnum & Bailey, which visited Prague in 1901, with its colossal menagerie in tow, during its five-year European tour of 1897-1902. Karel Kludský also became a remarkable animal trainer, working indifferently with tigers, lions, hyenas, bears, elephants, and all sorts of exotic animals. For decades, Cirkus Kludský provided animal acts for some of Europe’s major animal trainers and circuses.

Despite its increasing success, Cirkus Kludský (whose title was often Grand Cirque Kludsky, in French—after the fashion of the time) had its share of problems. Traveling circuses’ worst enemies are bad weather, war, and in the case of Cirkus Kludský, the poisoning of its animals. Its big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) was destroyed several times, notably twice in 1906, in storms in Rijeka, in Croatia, and in Trieste (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), and later in a snowstorm in Trento (Italy) in 1911. But that was nothing compared to the string of poisoning that occurred in the menagerie in 1902, and continued unsolved for ten years until Karel finally decided to lay off all his employees and hire a new staff!

The First World War also hurt the circus considerably: Its performers and staff enlisted, the Army took the circus’s horses away, and there was a food shortage that made it difficult to feed the people, let alone the animals. The star elephant Baby, who weighed 6,600 pounds (metric) in 1914, weighed less than three tons (metric) at the end of the war. Of 400 animals in the Kludský menagerie, just sixteen survived the war.It was not enough to discourage Karel however and, the war over, he and his sons patiently rebuilt their circus step-by-step, until it finally reached its pre-war level in 1922.In the mid-1920s, Karel Kludský bought a property in the city of Jirkov (Görkau in German), in the Ústí nad Labem Region—in the northeast of what had become the Republic of Czechoslovakia, near the German border. It was a large house located at Vinařická 363, with attenant land and buildings where he established his circus‘s winterquarters and his family’s residence. The Kludskýs became involved in local life, organizing notably circus parades for the carnival season—spectacular events involving up to 19 elephants, 25 camels, 50 horses, etc.—which locals remembered fondly for many years.

Baby (1847-1932), the oldest elephant of the Kludský menagerie, who had become an iconic and much cherished figure of the circus, assisted the railway station staff occasionally in loading merchandise on the trains—indeed a good publicity stunt. The city of Jirkov is still proud of its past association with the Kludský family; their house, the Villa Kludský, which was transformed into a military office after the communist revolution and had known various uses afterwards, has been restored in 2007. It is home today to a library, where visitors can see many mementos of the Kludský family and of Jirkov’s participation in Czech circus history.

Yet, in 1925, the Carnevale of Turin, in Italy, finally got the best of Karel Kludský: The shouting of the crowd and the noise of the fireworks frightened his elephants, which resulted in a stampede that caused considerable damage. Karel, who was sixty-one years old, had a nervous breakdown and finally retired in Jirkov. The following year (1926), his sons Karel, Jr. and Rudolf took over the management of Cirkus Kludský. On August 8, 1927, Karel Kludský passed away in his home. He was put to rest in the Kludský family crypt in Jirkov’s cemetery.

Karel II and Rudolf Kludský

Karel, Sr. and his wife Theresia (1869-1930—née Kneisel, and a former cat trainer(English/American) An trainer or presenter of wild cats such as tigers, lions, leopards, etc.) had three sons: Karel II (1891-1967), born June 3, 1891 in Timișoara, in Romania; Jindřich (1892-1914), who was killed in action at the outbreak of WWI; and Rudolf (1893-1960), born August 12, 1893 in Judenburg, in Austria. When he was thirteen, in 1904, Karel was sent by his father to Vienna, to learn horsemanship under Gustav Hüttemann, a circus equestrian who had opened there a highly respected riding school—made even more famous by the fact that Empress Elizabeth of Austria, better known as Sisi, had been one of Hüttemann’s students. Karel also learnt acrobatics under various teachers.

Back to the family circus, Karel proved himself an excellent equestrian, but he was also a good all-around animal trainer and his true passion was elephants. In 1906, his father had presented him with the elephant Baby, who became the symbol of Circus Kludský, and the star of a herd of elephants that reached 25 heads at its peak—including an African elephant, Bubi, a rare occurrence at that time in any circus. Karel’s elephant act soon became legendary in the circus business.Karel, in effect, succeeded his father at the artistic helm of Cirkus Kludský. Rudolf, himself an excellent animal trainer who presented a large group of lions and tigers, took care of the circus’s administration, logistics, and marketing. The brothers continued to develop the circus, which had become a giant three-ring circus at the beginning of the 1925 season. (They had already experimented with a two-ring circus.) By 1929, Cirkus Kludský traveled with Europe’s largest menagerie, and only Circus Krone, in Germany, could compete with Cirkus Kludský for the title of "Europe’s largest circus." Then, in October 1929, Wall Street crashed in New York and the Great Depression soon followed. By 1931, it had hit Europe: Inflation was galloping, attendance plummeted, and it became increasingly difficult for the Kludskýs to feed their vast zoological collection.

To make matters worse, in the winter of 1931, two hundreds animals died of pneumonia. The following year, Baby, the circus’s iconic elephant, died in Timișoara, Karel’s birthplace in Romania. Karel was heartbroken by what proved to be a very bad omen. In February 1934, the circus was playing in Vienna when the Austrian Civil War erupted (on February 12). The giant circus was stranded in a country that was paralyzed by a general strike, and couldn't go anywhere; understandably, the artists were concerned for their safety and deserted. That was the end of the glorious Cirkus Kludský: Karel and Rudolf had no choice but to declare bankruptcy on February 22, 1934.

The End of the Road

The Kludskýs had to dispose of what was left of their vast menagerie, including the herd of 24 elephants, which they had been trying to sell since 1932. The German animal dealer Alfred Ruhe was contacted to find buyers; he made a deal with the brothers Amar, owners of France’s largest circus at the time, who acquired sixteen elephants, a group of tigers, and many horses; other elephants were sold to Circus Barley in Germany. Rudolf’s son-in-law, Borislav Milojković (1921-1998, who was to become the legendary pickpocket Borra), inherited three of them which he contracted with other circuses for a few seasons. Other animals were either sold or given to zoos.The Anschluss (the union of Germany and Austria) was declared in 1938, and the Nazis annexed Chechoslovakia the following year. In effect, WWII had started. Rudolf, who is said to have cried like a child when he had to part with his animals, was a broken man; since he was Austrian by birth, he left Jirkov and Czechoslovakia in 1943 and re-settled with his wife, Inge, in Vienna—where a large part of the family archive was lost in the Allied bombings. In 1950, he published a book of memoirs, Könige der Manege. Rudolf Kludský passed away on December 4, 1960.

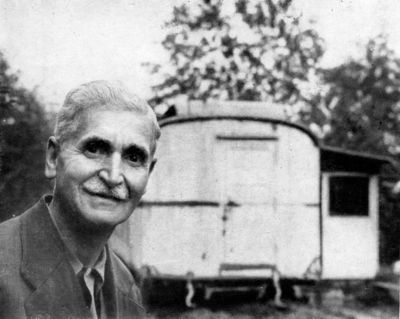

Karel tried to perform for a while as a horse trainer in another Circus Kludský that belonged to his cousins, but unfortunately the experience was not successful. After the War, in 1948, Czechoslovakia began a long, forty-year period of communist regime. The Villa Kludský in Jirkov was confiscated and used as headquarters for the local military garrison, and Karel and his wife Elsa (they were childless) were forced to leave their home of more than twenty years.

Karel Kludský was persecuted by the new regime, and went on to work as porter in a sawmill. He and Elsa moved into a small house in the nearby village of Vinařice, in the courtyard of which they parked their old, luxurious caravan. This caravan, which had been a spectacular symbol of their circus status, had been custom-built in Hanover by a German company called Buschbaum. It is in this caravan that they actually took residence, remembering the lost glory of another era. The great animal trainer had now just a few dogs, but he couldn't resist training them for fun.Although he received a job offer from the Prague Zoo, he rejected it because he didn't want to live anywhere else than in his caravan. His small pension was not enough to survive properly however. Karel and Elsa were not gardeners and thus were not able to improve their situation as other villagers did; yet from time to time someone stopped by, bringing them produce, or some cooked dishes, or a piece of cake—even some clothing. And whenever a circus came around, the performers raised money for the old circus king who still had the respect of the profession.

In the 1960s, Karel finally received the title of Honored Artist of the Republic of Czechoslovakia, a long-overdue official recognition of his past career. Around the same time, the journalist Václav Cibula wrote with him an autobiography, Zivot v manezi ("Life in the ring"). Until the end of his life, Karel could remember the names of each and everyone of his elephants, when they came to the circus, and the exact order in which they entered the ring. Karel Kludský died on November 29, 1967, in his caravan. On his last trip to the Jirkov cemetery, he was accompanied by hundreds of people—in large part former artists and employees who had never forgotten the glory of the great Cirkus Kludský. (Elsa, his wife, passed away in 1974.)

Epilogue

In 1951, the Czech circuses were nationalized and set up into a State Circus, Variety and Fairground Organization. The new State company possessed itself of the name of Cirkus Kludský, among many other former circus titles, and seized the equipment of existing circuses. Privately owned circuses disappeared, and the circus industry fell into the hands of indifferent bureaucrats. Many artists went to seek employment in West-European countries.

Nonetheless, the vast Kludský family provided artists who performed with success at home in the State circuses, as well as abroad. Among them, the 6 Kludskýs and their unicycle act, and the sisters Alice, Edith, and Dagmar Kludský, who worked with their mother, Božena, in a dancing act, presented trained pigeons, and had a Cowgirl act which they performed in variety theaters and nightclubs. After the Velvet Revolution of 1989, Bohumil Kludský (b.1944), tried to launch a new Circus Kludský, but unfortunately the experiment was short-lived.Other projects such as a "Kludský Amusement Park" or a Hall of Fame called Kludskea in the National Museum failed to take shape, but there are still members of the Kludský family in the circus today—such as the equestrian David Kludský, and the chimpanzee and elephant trainer Georg Kludský (the twin brother of Bohumil), who lives in Spain. Dagmar Kludská, a daughter of Josef Kludský (one of Antonín’s many grandsons) is a well-known astrologist, fortuneteller, and author; and the famous Czech pop singer Michal David also comes from the Kludský dynasty.

The Kludský family has a place of honor in the Czech Puppet and Circus Museum in the city of Prachatice, and a bust of Karel Kludský II was unveiled in 2007 in the Library of Jirkov—located in the restored Villa Kludský. It is not surprising that a family with such a dramatic history became the inspiration of the Czech author Eduard Bass (1888-1946) for his best-seller novel, Cirkus Humberto, published in 1941. Likewise the Czech artist Josef Lada (1887-1957) sketched animals at Circus Kludský for his children-book illustrations. In Horni Počernice, a municipal district of Prague, Kludských Street has been named for the great circus dynasty: The glorious name has not died.

Suggested Reading

- Rudolf Kludský, Könige der Manege ("Kings of the Ring") (Vienna, Paul Zsolnay Verlag, 1950)

- Karel Kludský and Václav Cibula, Zivot v manezi ("Life in the ring") (Prague, Orbis, 1966)

- Tonda Hančl, Ejhle, cirkusy a variete: Prvni cesky cirkusovy slovnik ("Lo and Behold, circus and variety: First Czech circus dictionary") (Brno, Rovnost, 1995) — ISBN 978-8085826098

- Dagmar Kludská, Vzpomínky schované v duši: historie rodiny Kludských ("Memories hidden in the soul: the history of the Kludský family") (Prague, Brána, 2005) — ISBN 80-7243-239-7

See Also

- Video: Cirkus Kludsky at Novi Sad, Serbia (1929)

- Video: Cirkus Kludsky, Documentary featuring Karel Kludsky (1967)

- Video: Cirkus Kludsky's images from Christoph Enzinger's Archive

- Video: Georg & Yvonne Kludsky, elephant act (2008)