Difference between revisions of "Yury Nikulin"

From Circopedia

(→Image Gallery) |

|||

| (188 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[File:Yury_Nikulin_clown.jpg|right|300px]] | ||

==Clown, Actor, Circus Director== | ==Clown, Actor, Circus Director== | ||

| − | + | ''By Dominique Jando'' | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Yury Nikulin (1921-1997) was the Soviet Union’s (and later, Russia’s) greatest and most beloved clown, as well as a remarkable and equally beloved screen actor; his performing career covered more than three decades, from 1948 to 1981. Upon his retirement from the ring, he became Director of Moscow's "[[Circus Nikulin|Old Circus]]" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, which he had entirely rebuilt (from 1985-1989) into a modern facility by a Finnish company, thus bringing that cherished Moscow institution into the modern age, and restoring its prominence on the Russian and European circus scenes at a critical moment in Russian history. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Early Years=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yury Vladimirovich Nikulin (Юрий Владимирович Никулин) was born in a theatrical family on December 18, 1921, in Demidov, a small town in the province of Smolensk, in northwest Russia, near the Belarussian border. His father was Moscow-born Vladimir Andreyevich Nikulin (1898-1964); his mother, Lidiya Ivanovna Nikulina (1902-1979), was born Lidia Germanova in Lievenhof (today's Līvāni) in Latvia, which was then part of the of the Russian Empire; she had moved to Demidov with relatives during the First World War to stay away from the combat zone. There, she met and married Vladimir Andreyevich. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Yury_Nikulin_on_Front.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Yury Nikulin (seated, 2nd from left) and his war comrades (1943)]]When Yury was born, Vladimir Nikulin had just been discharged from the Red Army and got a job at the Drama Theater in Demidov, where Lidia also worked as an actress. Then, he organized a traveling propaganda-theater group that promoted the brand-new Soviet regime through "revolutionary humor," and acted in plays which he also directed. In 1925, the Nikulin family moved to Moscow, where Vladimir wrote sketches for circus and variety shows—which were still intensely politicized then. He also organized the theater group at the school his son, Yury, attended. Later, he became a journalist. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On November 18, 1939, after graduating from high school, young Yury Nikulin was drafted into the Red Army for his three-year mandatory military service. This would have a long-lasting impact on Yury Nikulin as a man: In June 1941, the USSR declared war on Germany and the Axis powers, and what will be known in Russia as "The Great Patriotic War" started. Yury Nikulin was then serving in the 115th anti-aircraft artillery regiment. During the Soviet-Finnish war (1939-1940), his anti-aircraft battery had guarded the air approaches to Leningrad. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The siege of Leningrad (St. Petersburg) started in 1941, and Yury and his regiment fought to save the old imperial capital. The siege of Leningrad by the Germans was particularly brutal. In 1943, Yury was hospitalized for shock-shell treatment (today known as PTSD), and was subsequently transferred to another anti-aircraft battalion, where he oversaw an intelligence department. He was in Courland, Latvia (which had been annexed to the USSR) when the war ended on May 9, 1945; he remained in the Red Army for another year and was demobilized, a decorated soldier, on May 18, 1946, with the rank of Senior Sergeant. For the rest of his life, Yury Nikulin never forgot his war companions; even at the height of his fame, he always remained "one of them." | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Apprenticeship=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yury ambitioned to continue the family tradition and become an actor—and more specifically, a movie actor. Since there was a pre-determined official path to everything in Soviet Russia, he applied to the All-Union State Institute of Cinema, where the powers that be decided that he had no acting abilities. Undeterred, he then turned to the Russian Institute of Theatre Arts (GITIS) where the selection committee also decided that Yury didn't show the necessary abilities to become an actor. Reasons for these decisions are everybody's guess but, in retrospect, they certainly showed a remarkable lack of perception. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Karandash.jpeg|thumb|right|300px|Karandash (c.1955)]]Finally, Yury's father, who had connections with the circus world, suggested that he tried the Clown Studio that was operating at the [[Circus Nikulin|Old Circus]] on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. Either the Studio instructors had a different concept of what defined acting abilities, or they were attracted by the comedic possibilities of Yury's lanky silhouette, but in any case, Yury Nikulin was accepted and began his apprenticeship under the watchful eye of the Soviet Union's greatest clown, [[Karandash]] (Mikhail Rumyantsev, 1901-1983). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Karandash (which means "Pencil" in Russian) was one of the first graduates of Moscow's [[State College for Circus and Variety Arts]] (better known in the West as the Moscow Circus School), which had been created in 1927 to produce a new generation of Soviet circus performers. (The circus had been nationalized, along with the other performing arts, in 1919.) A very talented auguste who had taken his inspiration from Charlie Chaplin, Karandash had become extremely popular, even more so during "The Great Patriotic War," when his sarcastic parodies of Hitler and the German army offered comic relief (and revenge) to a population caught in the nightmare of a German military invasion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yury Nikulin made his clown debut in the ring of Tsvetnoy Boulevard on October 25, 1948, in a reprise that he performed with a fellow clown student at the Studio, [[Boris Romanov]] (who later became a successful circus director and dramaturgist). Karandash, who had a keen eye for talent, asked Nikulin to work with him as his assistant and occasional partner. He saw that Yury was what one calls "a natural;" he nurtured him and helped him develop his clown persona, that of a gangly, naïve and lazy character, whose hapless scheming put him in an interminable string of awkward situations—which he eventually overcame. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Scheming to circumvent the Soviet bureaucracy's endless regulations was a trait common to a large majority of Soviet citizens, and Soviet audiences quickly identified with Nikulin's character; his humor touched the right chord, and his clown persona had warmth and great humanity. He had, from the start, a minimal makeup, and his facial expressions were immediately readable and felt genuine. His little jacket and his pants, which were too small for his long-limbed figure, and his porkpie hat completed the image. Which is more, Yury Nikulin didn't need to overplay—or worse, to "play" a clown—to provoke laughter: He was indeed "a natural," as truly great clowns always are. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Enter Mikhail Shuydin=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Yury_and_Tatiyana_Nikulin.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Tanya & Yury Nikulin (c.1950)]]In 1949, Karandash needed a small horse for a comedy part in one of his shows. He found a small pony which was brought in by a young girl named Tatiyana (Tanya) Nikolaevna Pokrovskaya (1929-2014). Karandash introduced the pretty Tanya to Nikulin, who had to do a comic ride on a horse in the act. Yury invited her to watch the performance, intent as he was to show off and impress her. Unfortunately, he got his foot caught in a stirrup while he was performing a comic Cossack turn-around on his galloping mount and was trampled by his horse; he ended in hospital with a broken collarbone, scrapes on his leg and his head, and a black eye. Tanya visited him regularly in the hospital, bringing him fruits and little gifts. They fell in love and got married on May 23, 1950. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During these years, Nikulin met another Clown Studio apprentice, [[Mikhail Shuydin]] (1922-1983). Before joining the Studio, Shuydin had graduated from Moscow's State College for Circus and Variety Arts. In 1950, like Nikulin, he became an assistant, pupil, and occasional partner to Karandash. Yury and Mikhail were practically the same age, and they shared a military experience; Mikhail had been demobilized in 1944 with the rank of Senior Lieutenant after one of his several sojourns in hospital for injuries, and had been awarded the Order of the Red Banner, one of the USSR's highest military honors. Mikhail Shuydin was a man to Yury's liking. They struck a friendship and decided to work together. | ||

| + | |||

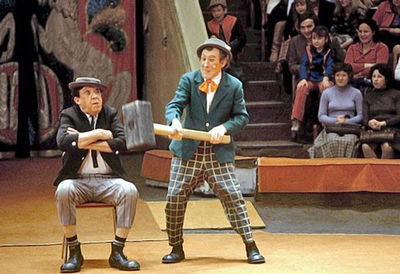

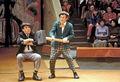

| + | [[File:Nikulin_and_Shuydin.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Nikulin & Shuydin (c.1960)]]Their clown characters were different, and thus complementary: Whereas Nikulin was tall, shy, and gangly, Shuydin was short, neat, self-important, a daring (and hapless) go-getter. It was a perfect comedic balance. The year 1950 saw other changes: Yury was now married, and he and Shuydin had a disagreement with Karandash over work. They decided to leave him and go their own way. Nikulin and Shuydin, along with Tanya who now participated in some of their entrées, went on to tour the Soviet circus circuit and honed their skills in front of increasingly appreciative audiences. Nikulin and Shuydin association would last, unabated, their entire clown career, until Nikulin retirement form the ring in 1981 (at age sixty)—which was sadly followed by Shuydin's passing the following year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Their growing success led them to become staples of Mosow's Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, the Soviet Union's premier circus, which served as a showcase for the USSR's major circus stars—of which, by the late 1950s, there were many. To a large extent, they had supplanted Karandash as Russia's favorite clowns: They had now a large repertoire of entrées and reprises; their humor was similar in many respects, but Karandash was aging and Nikulin and Shuydin were better attuned to the times. Their fame was to get a significant boost when, in 1958, Nikulin saw his dream of being a movie actor come true. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1958, he was cast as an inept fireworks worker by film director Aleksandr Fayntsimmer in his movie ''The Girl with a Guitar.'' It was a semi-propaganda film produced to celebrate the 6th World Youth Festival (1957), a major Soviet international event, and it was banking on the enormous popularity of a young Russian pop singer, Lyudmila Gurchenko (1935-2011). It premiered on September 1, 1958, and was a huge success, notably among the Russian youth. Nikulin's performance, in which his movie character reflected his clown persona, was indeed noteworthy. The film was seen by thirty-two million spectators (according to Soviet sources), and Yury Nikulin became instantly a national celebrity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His new-found glory didn't go to his head, and he didn't give up clowning: On the contrary, his popularity as a circus clown grew exponentially, since in time, audiences wanted more and more to see Nikulin live—and they were not disappointed: The Nikulin they saw in the circus ring was the same as the Nikulin they saw on the screen. Although he certainly became one, Nikulin never pretended to be a star. In the ring, it was always "Nikulin and Shuydin:" Yury and Mikhail shared the bill evenly and partook together in the fruits Yury's acting fame brought to the duo. It will remain so until the end of their joint clown career. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Nikulin's Movie Career=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nikulin,_Vitsin,_Morgunov.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Yury Nikulin, Georgiy Vitsin & Yevgeniy Morgunov (1966)]]Nikulin had a strong presence on screen; as in the ring, he didn't overplay and remained natural and completely believable—and most importantly, likeable. He played an everyday Russian guy caught in laughable situations, and as they did at the circus, audiences related to Nikulin's true-to-life character on the screen. Unlike the All-Union State Institute of Cinema's selection committee, movie directors were quick to notice that Yury Nikulin had a huge potential as a comic actor. For his directorial debut in 1959, Yury Chulyukin gave Nikulin a relatively small but significant part in his award-winning movie ''Неподдающиеся'' ("Stubborn"), starring Nadezhda Rumyantseva and Yury Belov (no relation with the clowning teacher of the same name). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Afterwards, Yury Nikulin got small parts in three other films in 1960-1961. Then, in 1961, his big break came with a short film directed by Leonid Gaïdaï (1923-1993), who was to become one of the Soviet Union's brightest and most successful directors of comedies. The film was part of a compilation of comedy shorts by various directors titled ''Absolutely Seriously''. Gaïdaï's film, ''The Dog Barbos and The Unusual Cross'' ("Пёс Барбос и необычный кросс") involved a trio of hapless characters played by Yury Nikulin, Georgiy Vitsin (1917-2001), and Yevgeniy Morgunov (1927-1999)—defined respectively as "The Fool," "The Coward," and "The Pro." The trio's chemistry worked wonders and the film was an unmitigated success. Together, Nikulin, Vitsin and Morgunov were on their way to write a chapter of Soviet cinema history. | ||

| + | |||

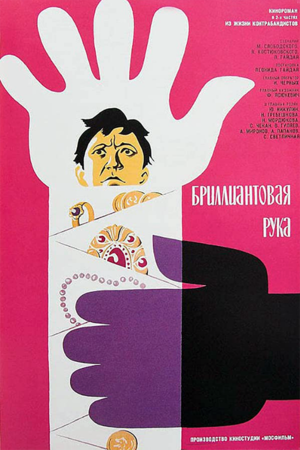

| + | [[File:Nikulin_Diamond_Arm.png|thumb|right|300px|Poster for ''The Diamond Arm'' (1969)]]Nikulin went on to make a long string of movies with other directors, but its most successful and long-lasting films were directed by Leonid Gaïdaï. After their success in ''The Dog Barbos'', Gaïdaï immediately reunited the trio in another comedy, ''Bootleggers'' ("Самогонщики", 1961), which was another hit. In terms of popularity, the trio became the Soviet equivalent of a mixture of the Marx Brothers, Laurel and Hardy and the Three Stooges, all wrapped in one bag. They would appear together in three other extremely successful comedies directed by Gaïdaï, ''Strictly Business'' ("Деловые люди", 1962), based on a series of short stories by American writer O. Henry, ''Operation "Y" and Shurik's Other Adventures'' ("Операция «Ы» и другие приключения Шурика", 1965), and ''Kidnapping Caucasian Style, or Shurik's New Adventures'' ("Кавказская пленница, или Новые приключения Шурика", 1966). The two latter films set Soviet cinema's box office records. Unfortunately, due to disagreements between Leonid Gaïdaï and Yevgeniy Mordunov, the trio was dissolved after ''Kidnapping Caucasian Style'', but their films remain to this day among the most popular and celebrated comedies of the Soviet era. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Yet, Gaïdaï was not done with Yury Nikulin and, in 1969, he gave him star billing in his most successful film, ''The Diamond Arm'' ("Бриллиантовая рука", 1969). This hilarious comedy, which consecrated Yury Nikulin as one of Russia's greatest screen comedians and has become a Russian cult classic, is the third highest grossing film in the history of Soviet cinema—not to mention that it did also good business abroad. ''A Song About Hares'' ("Песня про зайцев"), which was sung by Nikulin in the film, became yet another tremendous hit: It entered the Russian songbook, and remained associated with Nikulin until the end of his life. Nikulin worked a last time with Leonid Gaïdaï in 1971, in his very successful film adaptation of Ilf and Petrov's 1928 novel, ''The Twelve Chairs'' ("Двенадцать стульев"). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Additionally, Yury Nikulin appeared with considerable success in dramatic parts in which he proved a remarkable actor, notably in Lev Kulidzhanov's psychological drama ''Kogda derevya byli bolshimi'' ("When the Trees Were Tall", 1961), and in Semyon Tumanov's ''Come to Me, Mukhtar!'' ("Ко мне, Мухтар!", 1964), adapted from Izrail Metter’s book. Nikulin played in a total of twenty-four films between 1959 and 1991, as well in a series of short films for children television in 1983 and a voice over for a cartoon, ''Бобик в гостях у Барбоса'' ("Bobik Visits Barbos"), in 1976. His last screen appearance was as himself in a children film by Vladimir Onishchenko, ''Captain Crocus'' ("Капитан Крокус"), adapted from a novel by Fyodor Knorre and whose action was set in a circus. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Tsvetnoy Boulevard=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nikulin_Tsvetnoy.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Nikulin statue in front of Circus Nikulin (2012)]]During all that time, Yury Nikulin continued to perform on Tsvetnoy Boulevard and elsewhere with Mikhail Shuydin, sometimes shooting a movie at Mosfilm Studio in the afternoon and rushing to the circus in his small roadster for his evening performance. More than once he arrived just in the nick of time, leaving his car improperly parked in the front of the circus, and rushed inside; cops were used to seeing that very recognizable car there in the evening and, knowing it was Nikulin's, just let it be. Today, Alexandr Rukavishnikov's bronze sculpture of Yury Nikulin in front of the circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard shows the familiar sight of the great clown rushing out of his badly parked roadster… | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1973, Yury Nikulin had been made "People's Artist of the USSR," the highest distinction given to an artist in the Soviet Union. (He would also receive later the medal of Hero of Russia, the Russian Federation's highest award.) Meanwhile, on November 15, 1956, Tatiyana Nikulina had given Yury a son, [[Maksim Nikulin|Maksim Yuryevich]], who was to become a journalist and later, succeed his father at the helm of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. The "Old Circus," as it was known, was to take a very important place in the lives of Yury Nikulin and his son. To the people of Moscow, the "Old Circus" was part of the city's social fabric and of their own cultural heritage and DNA—and by the 1970s, Yury Nikulin, whose popularity was immense, had become closely associated with it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The circus had been inaugurated in 1880 by the brilliant German equestrian and circus director [[Albert Salamonsky]] (1839-1913). It had been taken over by the Soviet State in 1919, when circus was nationalized along with other performing arts. In 1932, Salamonsky's majestic and elegant building had been demolished and replaced by a new building, more "democratic"—and quite uninspiring—in appearance; it remained nonetheless very popular, and its house, which retained a classic elegance, had warmth and charm. Unfortunately, like many other public buildings of the Soviet era, it had been badly built, and not well maintained by the bureaucrats who oversaw it.[[File:Tsvetnoy_Blvd_(c.1970).jpg|thumb|right|400px|The Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1980)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, in the 1980s, things began to change in the Soviet Union. In 1979, Leonid Brezhnev (who would die three years later) started the new "Perestroika" policy, aimed at reforming the political and economic systems of the USSR. The circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard was then in a dire state of disrepair, and [[Oleg Popov]] and Yury Nikulin, the most renowned and respected figures of the Soviet circus, jumped on the new opportunity and joined forces to meet Pyotr Demichev, the minister of Culture, to convince him that the circus had to be rebuilt. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The circus was kept in high consideration in the USSR then (in no small part because its very successful foreign tours brought in much needed foreign currency to the cash-strapped Soviet Union), and Popov and Nikulin succeeded in their request. It is quite conceivable that, in the eyes of Soviet leaders, rebuilding this iconic place of entertainment in the capital could be seen as a potent symbol of a new era of changes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1981, Yury Nikulin and Mikhail Shuydin, retired from the ring; they were sixty and sixty-one years old, respectively. Mikhail Shuydin, who was in poor health, died soon after, in August 1983. It is also in 1981 that Nikulin was given the direction of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, with the task of organizing and overseeing its reconstruction. Oleg Popov, who had a high opinion of his own importance, resented the fact that Nikulin had been chosen over him; however, if Popov was indeed famous all over the world and was the unofficial Soviet Union's "Goodwill Ambassador," Yury Nikulin (who was his senior, anyway) was much more popular than him at home—and, furthermore, he had better personal connections, who kept him in higher regard than they did with the demanding Popov.[[File:Nikulin_and_Shuydin_-_hammer.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Nikulin & Shuydin at the Old Circus (c.1980)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nikulin didn't see his new position as a sinecure: He was genuinely attached to the circus that had seen his triumphs and, a fundamentally generous man, he had always been attentive to his fellow performers' needs—which had made him truly beloved in the profession. He was intent on building a modern and practical facility adapted to the needs of the future—and on building it swiftly and efficiently, without Soviet bureaucrats' interfering. To do that, he turned to a private company named "Polar," in neighboring Finland. Nikolai Ryzhkov, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, helped him raise the money. Thus, on August 13, 1985, the "Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard" gave an emotional last performance, before being torn down to make way for the new building. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The construction didn't go without problems—although they were not related to the physical aspect of the work. The choice of a foreign company had been resented by Soviet "businessmen" and high-level bureaucrats, since it hampered their age-long practice of bribes, favoritism and kickbacks which had been the rule in the Communist regime and had provided them with an additional source of income; in fact, this had been one of the reasons for the implementation of "Perestroika"—as well as for Nikulin's choice of a non-Russian company. Nevertheless, and despite threats and meddling attempts, the work continued unabated. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Circus Nikulin=== | ||

| + | |||

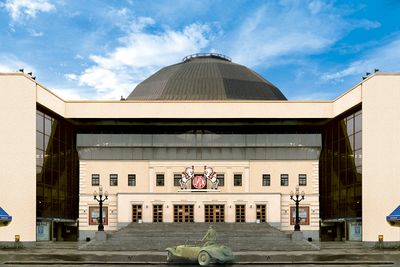

| + | Four years later, on September 29, 1989, a brand-new circus opened its doors on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. With a seating capacity of 2,000, it was a much larger building than its predecessor, and its cupola has been considerably elevated, allowing the presentation of the new giant flying acts that had been the exclusive domain of the huge [[Bolshoi Circus]] on Vernadsky Avenue (then known as the "New Circus"). Built in 1971, the Bolshoi Circus had become SoyuzGosTsirk's principal vitrine, dethroning the "Old Circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. By 1989, however, the "New Circus" itself was in need of repairs, and for all its technology, it now looked outdated in comparison with Nikulin's new building.[[File:Circus_Nikulin_(façade).jpg|thumb|right|400px|Nikulin's circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1998)]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a circus insider and performer, and unlike most of the Soviet bureaucracy's decision makers, Yury Nikulin had remained attentive to the needs of his colleagues as well as that of their audiences. His new circus was, for its artists and employees, a comfortable, well-appointed building, with nice dressing rooms, offices and workshops, a rehearsal studio with a full ring and enough height to accommodate aerial practice, and spacious rooms for the good keeping of animals. Nikulin had ensured, too, that its audiences would not be disconcerted by a completely different version of a place they had cherished: To everybody’s relief, the house resembled the old one and had retained its warmth, with its characteristic columns and color scheme—and one still could see the old façade, even though it was now encased within a huge, modern glass frontage. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mikhail Gorbachev had become General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1985, and boosted Brezhnev's old Perestroika policy with the introduction of his Glasnost strategy: Seismic changes were imminent in the Soviet Union and in 1987, well aware of it, Yury Nikulin had given the position of General Manager to his very capable son, Maksim, keeping the title of Artistic Director for himself—and thus securing a tight control on his circus during these uncertain times. Then, Maksim Nikulin negotiated the independence of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard from SoyuzGosTsirk, which had become a new entity known as RosGosTsirk. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nikulin_Lushkov.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Nikulin and Yury Lushkov at Nikulin's 75th Anniversary Gala (1996)]]From 1988 to 1991, the Soviet Union disintegrated, until it ceased to exist in December of 1991. These years marked indeed the beginning of a turbulent era that saw the rise of oligarchs and a powerful Russian mafia (often one and the same) all over the former Soviet Union. Calling themselves "businessmen," they tried to gain control of everything that could yield easy money—by intimidation and violence if necessary. For Yury Nikulin, navigating these murky waters was indeed a wearysome task, and it was not without risks: In August 1993, Mikhail Sedov the deputy director of the circus was shot dead in front of his home, mafia-style. It was a contract killing: Sedov had negotiated a possible take-over of the circus by a joint venture involving an American company, starting with a hold on its concessions business. Apparently, Sedov had not performed his end of the bargain to the Russian partners' liking. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Like most Russians that had been used to the tightly controlled ways of the Soviet era, Yury Nikulin lacked business savvy and was prone to being manipulated by unsavory characters. He was in a difficult and very dangerous situation, from which he was saved by a close friend, the colorful and powerful Yury Luzhkov (1936-2019), Moscow's new mayor, who decreed that the new venture controlled by the American company was unethical and illegal, and the contract had therefore to be annulled. The circus finally regained its independence—which it has kept ever since. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In August 1996, Moscow celebrated Yury Nikulin's seventy-five birthday at the circus, in presence of all the Russian circus, cinema and politics luminaries; Moscow's Mayor, Yury Lushkov, who had broken his leg, was rolled into the ring in a wheelchair, with his cast covered with fake diamonds, in reference to Nikulin's greatest screen success, ''The Diamond Arm''. It was a memorable evening, which was widely related by the Russian medias, including a broadcast on Russian television. As a tribute to the great clown, on December 8, the circus had been officially renamed ''Circus Nikulin''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Epilogue=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nikulin_Tomb.jpg|thumb|right|400px|Nikulin's tomb at Novodevichy Cemetery (2015)]]Sadly, his anniversary celebration was to be last appearance of Yury Nikulin in the ring. He died from complications following heart surgery in a Moscow hospital on August 22, 1997. ''Izvestia'', the Russian newspaper of reference, said in its report that Nikulin "was one of us, very close to each of us." Such was Yury Nikulin's place in the Russian psyche that Russian president Boris Yeltsin appeared on television that very same evening for an emotional address, in which he echoed the comments made by ''Izvetsia'': "Everybody loved him—from the small to the great." During his stay in the hospital, health bulletins had been issued every day, as it would have been done for a head of state. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The doctor who announced publicly Nikulin's passing did so with tears in his eyes. When Russia's Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin had visited him in hospital a week earlier, he had reminded the doctors that Nikulin was "very important to Russia." Reports on his death and reactions to what became a true national tragedy dominated the news for days. Tass, the state news agency, said that "Russia became an orphan after losing its unique and beloved actor." Even the American ''The New York Times'' chimed in, calling him a "Beloved Russian Master Comic," and noted that "he once explained his goal as trying to 'fish love out of people' and preached the power of laughter to help people overcome suffering." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nikulin's body laid in state in the ring of Circus Nikulin for several days; thousands of Muscovites lined the sidewalk to pay a last tribute to their beloved clown, whose body rested in an open casket surrounded by an honor military guard. On August 27, after a last ceremony at the circus, he was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, the place where Soviet and Russian celebrities from politics, science, and the arts are brought to rest. (Next to his is the resting place of Raïsa Gorbacheva.) Eight trucks were necessary to transport all the floral tributes that had been brought to the circus. On his tomb, a statue by the sculptor Aleksandr Rukavishnikov (the author of the monument erected in front of Circus Nikulin) represents the great clown, seated on a ring curb, his favorite dog, a giant schnauzer, lying next to him. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Nikulin_Banknotes.jpg|thumb|left|400px|Russian banknotes celebrating Yury Nikulin (2021)]]Besides his talent as a movie actor and as a clown, Nikulin was known as a great joke teller; Nikulin's jokes ("anecdotes" in Russian) were often quoted, and compilations of them were published in book form. This had led in 1993 to the creation of a very popular television show, ''The White Parrot Club'', which used Yury Nikulin's talent as a joke teller; it ended when Yury Nikulin passed away. Although there were other joke tellers with him on the show, the producers judged that its audience had tuned in principally to see Nikulin telling his jokes, and he couldn't be replaced—so great was his place in the Russian people's heart. | ||

| + | |||

| + | December 18, 2021 marked the one-hundredth anniversary of Yury Nikulin's birth. Once again, tributes, special documentaries and reminiscences of all sorts inundated the Russian medias. On the occasion, a commemorative medal was issued, as well as a commemorative 100 rubles banknote bearing his image. Twenty-four years after his death, the beloved Yury Nikulin had remained, for the Russian people, their favorite clown and comic actor, and more importantly, "one of us." | ||

==Suggested Reading== | ==Suggested Reading== | ||

| − | * Aleksandr Drigo, | + | * Aleksandr Drigo, Sofiya Rives, Elena Dukelskaya, ''Мир Цирка — Клоуны'' ("The Circus World — Clowns") (Moscow, Kladez Publishing, 1995) |

* Yury Dmitriev, ''Мой старый Цирк, бульвар Цветной'' ("My old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard") (Moscow, Lazur, 2000) | * Yury Dmitriev, ''Мой старый Цирк, бульвар Цветной'' ("My old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard") (Moscow, Lazur, 2000) | ||

* Yury Nikulin, ''Почти Серьезно'' ("Almost Serious") (Moscow, ACT Publishing, 2008) — ISBN 978-5-17-055586-4 | * Yury Nikulin, ''Почти Серьезно'' ("Almost Serious") (Moscow, ACT Publishing, 2008) — ISBN 978-5-17-055586-4 | ||

| − | ==See Also== | + | ==See Also== |

| + | * Biography: [[Mikhail Shuydin]] | ||

* History: [[Circus Nikulin]] | * History: [[Circus Nikulin]] | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Weight_Lifting_Video_(c.1965)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''The Weight Lifter'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1965) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Vodka_Bottle_Video_(c.1965)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''The Vodka Bottle'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1967) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Horses_Video_(1967)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''Hig School'' reprise]], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in Moscow (1967) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Bureaucrat_Video_(c.1968)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''Death of a Bureaucrat'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1968) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Log_Entree_Video_(c.1970)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''The Log'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1970) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Snake_Video_(c.1970)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''The Snake'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1970) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_-_Bet_Video_(1981)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''The Bet'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1981) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Shuydin_Video_1981|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''The Upsizing Machine'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard(1981) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Shuydin_TV_Video_(1981)|Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, ''The Television Set'']], at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1981) | ||

| + | * Video: [[Nikulin_Funeral_Video_(1997)|Yury Nikulin's Funeral (video clips)]], at Circus Nikulin in Moscow (1997) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Filmography== | ||

| + | |||

| + | * ''Девушка с гитарой'' (“The Girl with a Guitar”) (1958) | ||

| + | * ''Неподдающиеся'' (“Stubborn”) (1959) | ||

| + | * ''Мёртвые души'' (“Dead Souls”) (1960) | ||

| + | * ''Пёс Барбос и необычный кросс'' (“The Dog Barbos and The Unusual Cross”) '''(✻)''' – movie short, part of ''Совершенно серьезно'' ("Absolutely Seriously") (1961) | ||

| + | * ''Самогонщики'' (“The Bootleggers”) '''(✻)''' (1961) | ||

| + | * ''Когда деревья были большими'' (“When the Trees Were Tall”) (1961) | ||

| + | * ''Друг мой, Колька!'' (“My Friend, Kolka!”) (1961) | ||

| + | * ''Человек ниоткуда'' (“The Man from Nowhere”) (1961) | ||

| + | * ''Деловые люди'' (“Strictly Business”) '''(✻)''' (1962) | ||

| + | * ''Большой фитиль'' (“The Big Wick”) (1963) | ||

| + | * ''Ко мне, Мухтар!'' (“Come To Me, Mukhtar!”) (1964) | ||

| + | * ''Операция «Ы» и другие приключения Шурика'' (“Operation 'Y' and Other Shurik’s Adventures”) '''(✻)''' (1965) | ||

| + | * ''Дайте жалобную книгу'' (“Give Me the Complaint Book”) (1965) | ||

| + | * ''Кавказская пленница, или Новые приключения Шурика'' (“Kidnapping, Caucasian Style") '''(✻)''' (1966) | ||

| + | * ''Андрей Рублёв'' (“Andrei Rublev”) (1966) | ||

| + | * ''Семь стариков и одна девушка'' (“Seven Old Men and A Girl”) (1968) | ||

| + | * ''Бриллиантовая рука'' (“The Diamond Arm”) '''(✻)''' (1969) | ||

| + | * ''Старики-разбойники'' (“The Old Thieves”) (1971) | ||

| + | * ''12 стульев'' (“The Twelve Chairs”) '''(✻)''' (1971) | ||

| + | * ''Точка, точка, запятая…'' (“Dot, Dot, Comma…”) (1972) | ||

| + | * ''Они сражались за Родину'' (“They fought For Their Homeland”) (1975) | ||

| + | * ''Двадцать дней без войны'' (“Twenty Days Without War”) (1976) | ||

| + | * ''Бобик в гостях у Барбоса'' (“Bobik visits Barbos” — Cartoon, voice over) (1976) | ||

| + | * ''Чучело'' (“The Scarecrow”) (1983) | ||

| + | * ''Ералаш'' (“Short Comedies” — Children's TV Show) (1983) | ||

| + | * ''Капитан Крокус'' (“Captain Crocus”) (1991) | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''(✻)''': Films directed by Leonid Gaïdaï | ||

==Image Gallery== | ==Image Gallery== | ||

<Gallery> | <Gallery> | ||

| − | File:Nikulin_at_Tsvetnoy_Blvd_(c.1960).jpg|Yury Nikulin at the Old Moscow Circus (c.1960) | + | File:Nikulin_and_Mother.png|Yury Nikulin and his mother, Lidiya (c.1935) |

| + | File:Young_Nikulin.jpg|Young Yury Nikulin (c.1935) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Red_Army.jpg|Nikulin joins the Red Army (1939) | ||

| + | File:Yury_Nikulin_on_Front.jpg|Nikulin and his War Comrades (1943) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Army.jpg|Nikulin at the end of the war (c.1945) | ||

| + | File:Yury_and_Tatiyana_Nikulin.jpg|Yury and Tatiyana Nikulin (c.1950) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_at_Tsvetnoy_Blvd_(c.1960).jpg|Yury Nikulin at the Old Moscow Circus (c.1950) | ||

| + | File:Karandash.jpeg|Karandash (c.1955) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Shuydin_Kids.png|Yury Nikulin and Mikhail Shuydin and their sons (c.1960) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_and_Shuydin.jpg|Nikulin & Shuydin (c.1960) | ||

| + | File:Yury_Nikulin.jpg|Yury Nikulin (c.1965) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_and_Shuydin_-_Horses.jpg|Nikulin & Shuydin (c.1965) | ||

| + | File:Shuydin_and_Nikulin.jpg|Nikulin & Shuydin (c.1965) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Operation_Y.png|Poster for ''Operation Y'' (1965) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin,_Vitsin,_Morgunov.jpg|Nikulin, Morgunov and Vistsin (1966) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Gaidai_Kidnapping.jpg|Poster for ''Kidnapping Caucasian Style'' (1966) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Diamond_Arm_Poster.jpg|Poster for ''The Diamond Arm'' (1969) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Diamond_Arm.png|Poster for ''The Diamond Arm'' (1969) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_and_Shuydin_-_Camera.jpg|Nikulin & Shuydin (c.1970) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_and_Shuydin_Flyer.jpg|Nikulin & Shuydin Flyer (c.1970) | ||

| + | File:Yury_Nikulin_clown.jpg|Yury Nikulin (c.1970) | ||

File:Yury_Nikulin_(c.1970).jpg|Yury Nikulin (c.1970) | File:Yury_Nikulin_(c.1970).jpg|Yury Nikulin (c.1970) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_High-School.jpg|Nikulin & Shuydin (c.1970) | ||

| + | File:Yury_Nikulin_Moscow.jpg|Yury Nikulin (c.1975) | ||

| + | File:Tsvetnoy_Blvd_(c.1970).jpg|The Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1980) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_and_Shuydin_-_hammer.jpg|Nikulin & Shuydin (c.1980) | ||

File:Yury_Nikulin_(1989).jpg|Yury Nikulin in front of his circus (1989) | File:Yury_Nikulin_(1989).jpg|Yury Nikulin in front of his circus (1989) | ||

| + | File:Maxim_Nikulin.jpg|Maksim Nikulin (c.1990) | ||

| + | File:Yury_Nikulin_Old_Age.jpg|Yury Nikulin (c.1990) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Lushkov.jpg|Nikulin and Yury Lushkov (1996) | ||

File:Circus_Nikulin_(façade).jpg|Circus Nikulin with Yury Nikulin's statue (1998) | File:Circus_Nikulin_(façade).jpg|Circus Nikulin with Yury Nikulin's statue (1998) | ||

| − | File:Yury_Nikulin_Monument_(2012).JPG|Nikulin's | + | File:Yury_Nikulin_office.jpg|Yury Nikulin's office at the circus (c.2000) |

| + | File:Stamp_Nikulin_2001.jpg|Russian Postage Stamp honoring Yury Nikulin (2001) | ||

| + | File:Maksim_Nikulin.jpg|Maksim Nikulin (c.2010) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_-_Demidov.jpg|Nikulin monument in Demidov (2011) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Shuydin_Kursk.jpg|Monument to Nikulin & Shuydin in Kursk (2011) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Tyumen.jpg|Nikulin statue in Tyumen (2011) | ||

| + | File:Yury_Nikulin_Monument_(2012).JPG|Nikulin's monument on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (2012) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Tsvetnoy.jpg|Nikulin's monument on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (2012) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin-Vitsin-Morgunov_Perm.jpg|Monument to Nikulin, Morgunov and Vistsin in Irkutsk (2012) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Circus_Empty.jpg|Circus Nikulin's house (c.2015) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Tomb.jpg|Yury Nikulin's tomb (c.2015) | ||

| + | File:Russian_Anniversary_Postage_Stamp.png|Stamp issued for the 100th anniversary of the Russian State Circus (2019) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Monaco_Stamp.jpg|Monaco Postage Stamp celebrating Yury Nikulin's 100th anniversary (2021) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Zaika_Stamp.jpg|Kyrgyzstan Postage Stamp celebrating Yury Nikulin's 100th anniversary (2021) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Poster_Petersburg.jpg|Poster celebrating Nikulin at Circus Ciniselli in St. Petersburg (2021) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Banknotes.jpg|Russian banknote in tribute to Nikulin (2021) | ||

| + | File:Nikulin_Medal.jpg|Nikulin commemorative medal (2021) | ||

| + | File:Circus_Nikulin_Poster_2022.jpg|Poster for Circus Nikulin's show celebrating Yury Nikulin (2022) | ||

</Gallery> | </Gallery> | ||

[[Category:Artists and Acts|Nikulin, Yury]][[Category:Clowns|Nikulin, Yury]][[Category:Circus Owners and Directors|Nikulin, Yury]] | [[Category:Artists and Acts|Nikulin, Yury]][[Category:Clowns|Nikulin, Yury]][[Category:Circus Owners and Directors|Nikulin, Yury]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:31, 22 August 2022

Clown, Actor, Circus Director

By Dominique Jando

Yury Nikulin (1921-1997) was the Soviet Union’s (and later, Russia’s) greatest and most beloved clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., as well as a remarkable and equally beloved screen actor; his performing career covered more than three decades, from 1948 to 1981. Upon his retirement from the ring, he became Director of Moscow's "Old Circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, which he had entirely rebuilt (from 1985-1989) into a modern facility by a Finnish company, thus bringing that cherished Moscow institution into the modern age, and restoring its prominence on the Russian and European circus scenes at a critical moment in Russian history.

Early Years

Yury Vladimirovich Nikulin (Юрий Владимирович Никулин) was born in a theatrical family on December 18, 1921, in Demidov, a small town in the province of Smolensk, in northwest Russia, near the Belarussian border. His father was Moscow-born Vladimir Andreyevich Nikulin (1898-1964); his mother, Lidiya Ivanovna Nikulina (1902-1979), was born Lidia Germanova in Lievenhof (today's Līvāni) in Latvia, which was then part of the of the Russian Empire; she had moved to Demidov with relatives during the First World War to stay away from the combat zone. There, she met and married Vladimir Andreyevich.

When Yury was born, Vladimir Nikulin had just been discharged from the Red Army and got a job at the Drama Theater in Demidov, where Lidia also worked as an actress. Then, he organized a traveling propaganda-theater group that promoted the brand-new Soviet regime through "revolutionary humor," and acted in plays which he also directed. In 1925, the Nikulin family moved to Moscow, where Vladimir wrote sketches for circus and variety shows—which were still intensely politicized then. He also organized the theater group at the school his son, Yury, attended. Later, he became a journalist.On November 18, 1939, after graduating from high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école), young Yury Nikulin was drafted into the Red Army for his three-year mandatory military service. This would have a long-lasting impact on Yury Nikulin as a man: In June 1941, the USSR declared war on Germany and the Axis powers, and what will be known in Russia as "The Great Patriotic War" started. Yury Nikulin was then serving in the 115th anti-aircraft artillery regiment. During the Soviet-Finnish war (1939-1940), his anti-aircraft battery had guarded the air approaches to Leningrad.

The siege of Leningrad (St. Petersburg) started in 1941, and Yury and his regiment fought to save the old imperial capital. The siege of Leningrad by the Germans was particularly brutal. In 1943, Yury was hospitalized for shock-shell treatment (today known as PTSD), and was subsequently transferred to another anti-aircraft battalion, where he oversaw an intelligence department. He was in Courland, Latvia (which had been annexed to the USSR) when the war ended on May 9, 1945; he remained in the Red Army for another year and was demobilized, a decorated soldier, on May 18, 1946, with the rank of Senior Sergeant. For the rest of his life, Yury Nikulin never forgot his war companions; even at the height of his fame, he always remained "one of them."

Apprenticeship

Yury ambitioned to continue the family tradition and become an actor—and more specifically, a movie actor. Since there was a pre-determined official path to everything in Soviet Russia, he applied to the All-Union State Institute of Cinema, where the powers that be decided that he had no acting abilities. Undeterred, he then turned to the Russian Institute of Theatre Arts (GITIS) where the selection committee also decided that Yury didn't show the necessary abilities to become an actor. Reasons for these decisions are everybody's guess but, in retrospect, they certainly showed a remarkable lack of perception.

Finally, Yury's father, who had connections with the circus world, suggested that he tried the Clown Studio that was operating at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. Either the Studio instructors had a different concept of what defined acting abilities, or they were attracted by the comedic possibilities of Yury's lanky silhouette, but in any case, Yury Nikulin was accepted and began his apprenticeship under the watchful eye of the Soviet Union's greatest clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., Karandash (Mikhail Rumyantsev, 1901-1983).Karandash (which means "Pencil" in Russian) was one of the first graduates of Moscow's State College for Circus and Variety Arts (better known in the West as the Moscow Circus School), which had been created in 1927 to produce a new generation of Soviet circus performers. (The circus had been nationalized, along with the other performing arts, in 1919.) A very talented augusteIn a classic European clown team, the comic, red-nosed character, as opposed to the elegant, whiteface Clown. who had taken his inspiration from Charlie Chaplin, Karandash had become extremely popular, even more so during "The Great Patriotic War," when his sarcastic parodies of Hitler and the German army offered comic relief (and revenge) to a population caught in the nightmare of a German military invasion.

Yury Nikulin made his clown debut in the ring of Tsvetnoy Boulevard on October 25, 1948, in a reprise(French) Short piece performed by clowns between acts during prop changes or equipment rigging. (See also: Carpet Clown) that he performed with a fellow clown student at the Studio, Boris Romanov (who later became a successful circus director and dramaturgist). Karandash, who had a keen eye for talent, asked Nikulin to work with him as his assistant and occasional partner. He saw that Yury was what one calls "a natural;" he nurtured him and helped him develop his clown persona, that of a gangly, naïve and lazy character, whose hapless scheming put him in an interminable string of awkward situations—which he eventually overcame.

Scheming to circumvent the Soviet bureaucracy's endless regulations was a trait common to a large majority of Soviet citizens, and Soviet audiences quickly identified with Nikulin's character; his humor touched the right chord, and his clown persona had warmth and great humanity. He had, from the start, a minimal makeup, and his facial expressions were immediately readable and felt genuine. His little jacket and his pants, which were too small for his long-limbed figure, and his porkpie hat completed the image. Which is more, Yury Nikulin didn't need to overplay—or worse, to "play" a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.—to provoke laughter: He was indeed "a natural," as truly great clowns always are.

Enter Mikhail Shuydin

In 1949, Karandash needed a small horse for a comedy part in one of his shows. He found a small pony which was brought in by a young girl named Tatiyana (Tanya) Nikolaevna Pokrovskaya (1929-2014). Karandash introduced the pretty Tanya to Nikulin, who had to do a comic ride on a horse in the act. Yury invited her to watch the performance, intent as he was to show off and impress her. Unfortunately, he got his foot caught in a stirrup while he was performing a comic Cossack turn-around on his galloping mount and was trampled by his horse; he ended in hospital with a broken collarbone, scrapes on his leg and his head, and a black eye. Tanya visited him regularly in the hospital, bringing him fruits and little gifts. They fell in love and got married on May 23, 1950.During these years, Nikulin met another Clown Studio apprentice, Mikhail Shuydin (1922-1983). Before joining the Studio, Shuydin had graduated from Moscow's State College for Circus and Variety Arts. In 1950, like Nikulin, he became an assistant, pupil, and occasional partner to Karandash. Yury and Mikhail were practically the same age, and they shared a military experience; Mikhail had been demobilized in 1944 with the rank of Senior Lieutenant after one of his several sojourns in hospital for injuries, and had been awarded the Order of the Red Banner, one of the USSR's highest military honors. Mikhail Shuydin was a man to Yury's liking. They struck a friendship and decided to work together.

Their clown characters were different, and thus complementary: Whereas Nikulin was tall, shy, and gangly, Shuydin was short, neat, self-important, a daring (and hapless) go-getter. It was a perfect comedic balance. The year 1950 saw other changes: Yury was now married, and he and Shuydin had a disagreement with Karandash over work. They decided to leave him and go their own way. Nikulin and Shuydin, along with Tanya who now participated in some of their entrées, went on to tour the Soviet circus circuit and honed their skills in front of increasingly appreciative audiences. Nikulin and Shuydin association would last, unabated, their entire clown career, until Nikulin retirement form the ring in 1981 (at age sixty)—which was sadly followed by Shuydin's passing the following year.Their growing success led them to become staples of Mosow's Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, the Soviet Union's premier circus, which served as a showcase for the USSR's major circus stars—of which, by the late 1950s, there were many. To a large extent, they had supplanted Karandash as Russia's favorite clowns: They had now a large repertoire of entrées and reprises; their humor was similar in many respects, but Karandash was aging and Nikulin and Shuydin were better attuned to the times. Their fame was to get a significant boost when, in 1958, Nikulin saw his dream of being a movie actor come true.

In 1958, he was cast as an inept fireworks worker by film director Aleksandr Fayntsimmer in his movie The Girl with a Guitar. It was a semi-propaganda film produced to celebrate the 6th World Youth Festival (1957), a major Soviet international event, and it was banking on the enormous popularity of a young Russian pop singer, Lyudmila Gurchenko (1935-2011). It premiered on September 1, 1958, and was a huge success, notably among the Russian youth. Nikulin's performance, in which his movie character reflected his clown persona, was indeed noteworthy. The film was seen by thirty-two million spectators (according to Soviet sources), and Yury Nikulin became instantly a national celebrity.

His new-found glory didn't go to his head, and he didn't give up clowning: On the contrary, his popularity as a circus clown grew exponentially, since in time, audiences wanted more and more to see Nikulin live—and they were not disappointed: The Nikulin they saw in the circus ring was the same as the Nikulin they saw on the screen. Although he certainly became one, Nikulin never pretended to be a star. In the ring, it was always "Nikulin and Shuydin:" Yury and Mikhail shared the bill evenly and partook together in the fruits Yury's acting fame brought to the duo. It will remain so until the end of their joint clown career.

Nikulin's Movie Career

Nikulin had a strong presence on screen; as in the ring, he didn't overplay and remained natural and completely believable—and most importantly, likeable. He played an everyday Russian guy caught in laughable situations, and as they did at the circus, audiences related to Nikulin's true-to-life character on the screen. Unlike the All-Union State Institute of Cinema's selection committee, movie directors were quick to notice that Yury Nikulin had a huge potential as a comic actor. For his directorial debut in 1959, Yury Chulyukin gave Nikulin a relatively small but significant part in his award-winning movie Неподдающиеся ("Stubborn"), starring Nadezhda Rumyantseva and Yury Belov (no relation with the clowning teacher of the same name).Afterwards, Yury Nikulin got small parts in three other films in 1960-1961. Then, in 1961, his big break came with a short film directed by Leonid Gaïdaï (1923-1993), who was to become one of the Soviet Union's brightest and most successful directors of comedies. The film was part of a compilation of comedy shorts by various directors titled Absolutely Seriously. Gaïdaï's film, The Dog Barbos and The Unusual Cross ("Пёс Барбос и необычный кросс") involved a trio of hapless characters played by Yury Nikulin, Georgiy Vitsin (1917-2001), and Yevgeniy Morgunov (1927-1999)—defined respectively as "The Fool," "The Coward," and "The Pro." The trio's chemistry worked wonders and the film was an unmitigated success. Together, Nikulin, Vitsin and Morgunov were on their way to write a chapter of Soviet cinema history.

Nikulin went on to make a long string of movies with other directors, but its most successful and long-lasting films were directed by Leonid Gaïdaï. After their success in The Dog Barbos, Gaïdaï immediately reunited the trio in another comedy, Bootleggers ("Самогонщики", 1961), which was another hit. In terms of popularity, the trio became the Soviet equivalent of a mixture of the Marx Brothers, Laurel and Hardy and the Three Stooges, all wrapped in one bag. They would appear together in three other extremely successful comedies directed by Gaïdaï, Strictly Business ("Деловые люди", 1962), based on a series of short stories by American writer O. Henry, Operation "Y" and Shurik's Other Adventures ("Операция «Ы» и другие приключения Шурика", 1965), and Kidnapping Caucasian Style, or Shurik's New Adventures ("Кавказская пленница, или Новые приключения Шурика", 1966). The two latter films set Soviet cinema's box office records. Unfortunately, due to disagreements between Leonid Gaïdaï and Yevgeniy Mordunov, the trio was dissolved after Kidnapping Caucasian Style, but their films remain to this day among the most popular and celebrated comedies of the Soviet era.Yet, Gaïdaï was not done with Yury Nikulin and, in 1969, he gave him star billing in his most successful film, The Diamond Arm ("Бриллиантовая рука", 1969). This hilarious comedy, which consecrated Yury Nikulin as one of Russia's greatest screen comedians and has become a Russian cult classic, is the third highest grossing film in the history of Soviet cinema—not to mention that it did also good business abroad. A Song About Hares ("Песня про зайцев"), which was sung by Nikulin in the film, became yet another tremendous hit: It entered the Russian songbook, and remained associated with Nikulin until the end of his life. Nikulin worked a last time with Leonid Gaïdaï in 1971, in his very successful film adaptation of Ilf and Petrov's 1928 novel, The Twelve Chairs ("Двенадцать стульев").

Additionally, Yury Nikulin appeared with considerable success in dramatic parts in which he proved a remarkable actor, notably in Lev Kulidzhanov's psychological drama Kogda derevya byli bolshimi ("When the Trees Were Tall", 1961), and in Semyon Tumanov's Come to Me, Mukhtar! ("Ко мне, Мухтар!", 1964), adapted from Izrail Metter’s book. Nikulin played in a total of twenty-four films between 1959 and 1991, as well in a series of short films for children television in 1983 and a voice over for a cartoon, Бобик в гостях у Барбоса ("Bobik Visits Barbos"), in 1976. His last screen appearance was as himself in a children film by Vladimir Onishchenko, Captain Crocus ("Капитан Крокус"), adapted from a novel by Fyodor Knorre and whose action was set in a circus.

Tsvetnoy Boulevard

During all that time, Yury Nikulin continued to perform on Tsvetnoy Boulevard and elsewhere with Mikhail Shuydin, sometimes shooting a movie at Mosfilm Studio in the afternoon and rushing to the circus in his small roadster for his evening performance. More than once he arrived just in the nick of time, leaving his car improperly parked in the front of the circus, and rushed inside; cops were used to seeing that very recognizable car there in the evening and, knowing it was Nikulin's, just let it be. Today, Alexandr Rukavishnikov's bronze sculpture of Yury Nikulin in front of the circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard shows the familiar sight of the great clown rushing out of his badly parked roadster…In 1973, Yury Nikulin had been made "People's Artist of the USSR," the highest distinction given to an artist in the Soviet Union. (He would also receive later the medal of Hero of Russia, the Russian Federation's highest award.) Meanwhile, on November 15, 1956, Tatiyana Nikulina had given Yury a son, Maksim Yuryevich, who was to become a journalist and later, succeed his father at the helm of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. The "Old Circus," as it was known, was to take a very important place in the lives of Yury Nikulin and his son. To the people of Moscow, the "Old Circus" was part of the city's social fabric(See: Tissu) and of their own cultural heritage and DNA—and by the 1970s, Yury Nikulin, whose popularity was immense, had become closely associated with it.

The circus had been inaugurated in 1880 by the brilliant German equestrian and circus director Albert Salamonsky (1839-1913). It had been taken over by the Soviet State in 1919, when circus was nationalized along with other performing arts. In 1932, Salamonsky's majestic and elegant building had been demolished and replaced by a new building, more "democratic"—and quite uninspiring—in appearance; it remained nonetheless very popular, and its house, which retained a classic elegance, had warmth and charm. Unfortunately, like many other public buildings of the Soviet era, it had been badly built, and not well maintained by the bureaucrats who oversaw it.Then, in the 1980s, things began to change in the Soviet Union. In 1979, Leonid Brezhnev (who would die three years later) started the new "Perestroika" policy, aimed at reforming the political and economic systems of the USSR. The circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard was then in a dire state of disrepair, and Oleg Popov and Yury Nikulin, the most renowned and respected figures of the Soviet circus, jumped on the new opportunity and joined forces to meet Pyotr Demichev, the minister of Culture, to convince him that the circus had to be rebuilt.

The circus was kept in high consideration in the USSR then (in no small part because its very successful foreign tours brought in much needed foreign currency to the cash-strapped Soviet Union), and Popov and Nikulin succeeded in their request. It is quite conceivable that, in the eyes of Soviet leaders, rebuilding this iconic place of entertainment in the capital could be seen as a potent symbol of a new era of changes.

In 1981, Yury Nikulin and Mikhail Shuydin, retired from the ring; they were sixty and sixty-one years old, respectively. Mikhail Shuydin, who was in poor health, died soon after, in August 1983. It is also in 1981 that Nikulin was given the direction of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard, with the task of organizing and overseeing its reconstruction. Oleg Popov, who had a high opinion of his own importance, resented the fact that Nikulin had been chosen over him; however, if Popov was indeed famous all over the world and was the unofficial Soviet Union's "Goodwill Ambassador," Yury Nikulin (who was his senior, anyway) was much more popular than him at home—and, furthermore, he had better personal connections, who kept him in higher regard than they did with the demanding Popov.Nikulin didn't see his new position as a sinecure: He was genuinely attached to the circus that had seen his triumphs and, a fundamentally generous man, he had always been attentive to his fellow performers' needs—which had made him truly beloved in the profession. He was intent on building a modern and practical facility adapted to the needs of the future—and on building it swiftly and efficiently, without Soviet bureaucrats' interfering. To do that, he turned to a private company named "Polar," in neighboring Finland. Nikolai Ryzhkov, the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, helped him raise the money. Thus, on August 13, 1985, the "Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard" gave an emotional last performance, before being torn down to make way for the new building.

The construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." didn't go without problems—although they were not related to the physical aspect of the work. The choice of a foreign company had been resented by Soviet "businessmen" and high-level bureaucrats, since it hampered their age-long practice of bribes, favoritism and kickbacks which had been the rule in the Communist regime and had provided them with an additional source of income; in fact, this had been one of the reasons for the implementation of "Perestroika"—as well as for Nikulin's choice of a non-Russian company. Nevertheless, and despite threats and meddling attempts, the work continued unabated.

Circus Nikulin

Four years later, on September 29, 1989, a brand-new circus opened its doors on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. With a seating capacity of 2,000, it was a much larger building than its predecessor, and its cupola has been considerably elevated, allowing the presentation of the new giant flying acts that had been the exclusive domain of the huge Bolshoi Circus on Vernadsky Avenue (then known as the "New Circus"). Built in 1971, the Bolshoi Circus had become SoyuzGosTsirk's principal vitrine, dethroning the "Old Circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard. By 1989, however, the "New Circus" itself was in need of repairs, and for all its technology, it now looked outdated in comparison with Nikulin's new building.As a circus insider and performer, and unlike most of the Soviet bureaucracy's decision makers, Yury Nikulin had remained attentive to the needs of his colleagues as well as that of their audiences. His new circus was, for its artists and employees, a comfortable, well-appointed building, with nice dressing rooms, offices and workshops, a rehearsal studio with a full ring and enough height to accommodate aerial practice, and spacious rooms for the good keeping of animals. Nikulin had ensured, too, that its audiences would not be disconcerted by a completely different version of a place they had cherished: To everybody’s relief, the house resembled the old one and had retained its warmth, with its characteristic columns and color scheme—and one still could see the old façade, even though it was now encased within a huge, modern glass frontage.

Mikhail Gorbachev had become General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1985, and boosted Brezhnev's old Perestroika policy with the introduction of his Glasnost strategy: Seismic changes were imminent in the Soviet Union and in 1987, well aware of it, Yury Nikulin had given the position of General Manager to his very capable son, Maksim, keeping the title of Artistic Director for himself—and thus securing a tight control on his circus during these uncertain times. Then, Maksim Nikulin negotiated the independence of the Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard from SoyuzGosTsirk, which had become a new entity known as RosGosTsirk.

From 1988 to 1991, the Soviet Union disintegrated, until it ceased to exist in December of 1991. These years marked indeed the beginning of a turbulent era that saw the rise of oligarchs and a powerful Russian mafia (often one and the same) all over the former Soviet Union. Calling themselves "businessmen," they tried to gain control of everything that could yield easy money—by intimidation and violence if necessary. For Yury Nikulin, navigating these murky waters was indeed a wearysome task, and it was not without risks: In August 1993, Mikhail Sedov the deputy director of the circus was shot dead in front of his home, mafia-style. It was a contract killing: Sedov had negotiated a possible take-over of the circus by a joint venture involving an American company, starting with a hold on its concessions business. Apparently, Sedov had not performed his end of the bargain to the Russian partners' liking.Like most Russians that had been used to the tightly controlled ways of the Soviet era, Yury Nikulin lacked business savvy and was prone to being manipulated by unsavory characters. He was in a difficult and very dangerous situation, from which he was saved by a close friend, the colorful and powerful Yury Luzhkov (1936-2019), Moscow's new mayor, who decreed that the new venture controlled by the American company was unethical and illegal, and the contract had therefore to be annulled. The circus finally regained its independence—which it has kept ever since.

In August 1996, Moscow celebrated Yury Nikulin's seventy-five birthday at the circus, in presence of all the Russian circus, cinema and politics luminaries; Moscow's Mayor, Yury Lushkov, who had broken his leg, was rolled into the ring in a wheelchair, with his cast covered with fake diamonds, in reference to Nikulin's greatest screen success, The Diamond Arm. It was a memorable evening, which was widely related by the Russian medias, including a broadcast on Russian television. As a tribute to the great clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., on December 8, the circus had been officially renamed Circus Nikulin.

Epilogue

Sadly, his anniversary celebration was to be last appearance of Yury Nikulin in the ring. He died from complications following heart surgery in a Moscow hospital on August 22, 1997. Izvestia, the Russian newspaper of reference, said in its report that Nikulin "was one of us, very close to each of us." Such was Yury Nikulin's place in the Russian psyche that Russian president Boris Yeltsin appeared on television that very same evening for an emotional address, in which he echoed the comments made by Izvetsia: "Everybody loved him—from the small to the great." During his stay in the hospital, health bulletins had been issued every day, as it would have been done for a head of state.The doctor who announced publicly Nikulin's passing did so with tears in his eyes. When Russia's Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin had visited him in hospital a week earlier, he had reminded the doctors that Nikulin was "very important to Russia." Reports on his death and reactions to what became a true national tragedy dominated the news for days. Tass, the state news agency, said that "Russia became an orphan after losing its unique and beloved actor." Even the American The New York Times chimed in, calling him a "Beloved Russian Master Comic," and noted that "he once explained his goal as trying to 'fish love out of people' and preached the power of laughter to help people overcome suffering."

Nikulin's body laid in state in the ring of Circus Nikulin for several days; thousands of Muscovites lined the sidewalk to pay a last tribute to their beloved clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., whose body rested in an open casket surrounded by an honor military guard. On August 27, after a last ceremony at the circus, he was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, the place where Soviet and Russian celebrities from politics, science, and the arts are brought to rest. (Next to his is the resting place of Raïsa Gorbacheva.) Eight trucks were necessary to transport all the floral tributes that had been brought to the circus. On his tomb, a statue by the sculptor Aleksandr Rukavishnikov (the author of the monument erected in front of Circus Nikulin) represents the great clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., seated on a ring curb(American. French: Banquette. Russian: Barrier) The circular barrier that defines the ring, and separates it from the audience., his favorite dog, a giant schnauzer, lying next to him.

Besides his talent as a movie actor and as a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., Nikulin was known as a great joke teller; Nikulin's jokes ("anecdotes" in Russian) were often quoted, and compilations of them were published in book form. This had led in 1993 to the creation of a very popular television show, The White Parrot Club, which used Yury Nikulin's talent as a joke teller; it ended when Yury Nikulin passed away. Although there were other joke tellers with him on the show, the producers judged that its audience had tuned in principally to see Nikulin telling his jokes, and he couldn't be replaced—so great was his place in the Russian people's heart.December 18, 2021 marked the one-hundredth anniversary of Yury Nikulin's birth. Once again, tributes, special documentaries and reminiscences of all sorts inundated the Russian medias. On the occasion, a commemorative medal was issued, as well as a commemorative 100 rubles banknote bearing his image. Twenty-four years after his death, the beloved Yury Nikulin had remained, for the Russian people, their favorite clown and comic actor, and more importantly, "one of us."

Suggested Reading

- Aleksandr Drigo, Sofiya Rives, Elena Dukelskaya, Мир Цирка — Клоуны ("The Circus World — Clowns") (Moscow, Kladez Publishing, 1995)

- Yury Dmitriev, Мой старый Цирк, бульвар Цветной ("My old Circus, Tsvetnoy Boulevard") (Moscow, Lazur, 2000)

- Yury Nikulin, Почти Серьезно ("Almost Serious") (Moscow, ACT Publishing, 2008) — ISBN 978-5-17-055586-4

See Also

- Biography: Mikhail Shuydin

- History: Circus Nikulin

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, The Weight Lifter, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1965)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, The Vodka Bottle, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1967)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, Hig School reprise, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in Moscow (1967)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, Death of a Bureaucrat, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1968)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, The Log, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1970)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, The Snake, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (c.1970)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, The Bet, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1981)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, The Upsizing Machine, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard(1981)

- Video: Yury Nikulin & Mikhail Shuydin, The Television Set, at the Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard (1981)

- Video: Yury Nikulin's Funeral (video clips), at Circus Nikulin in Moscow (1997)

Filmography

- Девушка с гитарой (“The Girl with a Guitar”) (1958)

- Неподдающиеся (“Stubborn”) (1959)

- Мёртвые души (“Dead Souls”) (1960)

- Пёс Барбос и необычный кросс (“The Dog Barbos and The Unusual Cross”) (✻) – movie short, part of Совершенно серьезно ("Absolutely Seriously") (1961)

- Самогонщики (“The Bootleggers”) (✻) (1961)

- Когда деревья были большими (“When the Trees Were Tall”) (1961)

- Друг мой, Колька! (“My Friend, Kolka!”) (1961)

- Человек ниоткуда (“The Man from Nowhere”) (1961)

- Деловые люди (“Strictly Business”) (✻) (1962)

- Большой фитиль (“The Big Wick”) (1963)

- Ко мне, Мухтар! (“Come To Me, Mukhtar!”) (1964)

- Операция «Ы» и другие приключения Шурика (“Operation 'Y' and Other Shurik’s Adventures”) (✻) (1965)

- Дайте жалобную книгу (“Give Me the Complaint Book”) (1965)

- Кавказская пленница, или Новые приключения Шурика (“Kidnapping, Caucasian Style") (✻) (1966)

- Андрей Рублёв (“Andrei Rublev”) (1966)

- Семь стариков и одна девушка (“Seven Old Men and A Girl”) (1968)

- Бриллиантовая рука (“The Diamond Arm”) (✻) (1969)

- Старики-разбойники (“The Old Thieves”) (1971)

- 12 стульев (“The Twelve Chairs”) (✻) (1971)

- Точка, точка, запятая… (“Dot, Dot, Comma…”) (1972)

- Они сражались за Родину (“They fought For Their Homeland”) (1975)

- Двадцать дней без войны (“Twenty Days Without War”) (1976)

- Бобик в гостях у Барбоса (“Bobik visits Barbos” — Cartoon, voice over) (1976)

- Чучело (“The Scarecrow”) (1983)

- Ералаш (“Short Comedies” — Children's TV Show) (1983)

- Капитан Крокус (“Captain Crocus”) (1991)

(✻): Films directed by Leonid Gaïdaï