Difference between revisions of "Valentin Gneushev"

From Circopedia

(→Final Bow: The Gneushev Studio) |

(→Final Bow: The Gneushev Studio) |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

During the early 1990s, while Valentin’s acts were beginning to invade the best circuses and variety theaters of the planet, his base remained the Circus Studio in Moscow. But in spite of his numerous international awards and his obvious success, his artistic vision still contrasted with the politics of SoyuzGosTsirk (which, after the fall of the Soviet regime would be renamed RosGosTsirk). Still reveling on memories of its past glory, the old central circus organization seemed unable to truly appreciate the changes that their own Valentin Gneushev was bringing to the international circus scene. | During the early 1990s, while Valentin’s acts were beginning to invade the best circuses and variety theaters of the planet, his base remained the Circus Studio in Moscow. But in spite of his numerous international awards and his obvious success, his artistic vision still contrasted with the politics of SoyuzGosTsirk (which, after the fall of the Soviet regime would be renamed RosGosTsirk). Still reveling on memories of its past glory, the old central circus organization seemed unable to truly appreciate the changes that their own Valentin Gneushev was bringing to the international circus scene. | ||

| − | [[File:Borodina.jpg|thumb|left| | + | [[File:Borodina.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Elena Borodina]]Not surprisingly, in 1993, Gneushev decided to become an independent producer and began to attract young performers away from the State circus company, and to create acts for them that could be offered individually to the western market. [[Maxim Nikulin]], son of the legendary clown and actor [[Yury Nikulin]] (1921-1997), who had succeeded his father at the helm of the "Old Circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in Moscow (today [[Circus Nikulin]]) and had become one of the first Russian independent circus directors, offered Valentin a space in his circus to house the new Gneushev Studio. |

Not only did the Gneushev Studio become the main crucible of the post-Soviet circus experimentation, but Maxim Nikulin also expanded his association with Valentin, and asked him to stage two of his Circus’s productions, ''Sweet Love'' (1996) and ''Carnival'' (1997)—highly innovative and creative shows, as could be expected, which gave to the "Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard" a definitely new look. | Not only did the Gneushev Studio become the main crucible of the post-Soviet circus experimentation, but Maxim Nikulin also expanded his association with Valentin, and asked him to stage two of his Circus’s productions, ''Sweet Love'' (1996) and ''Carnival'' (1997)—highly innovative and creative shows, as could be expected, which gave to the "Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard" a definitely new look. | ||

Revision as of 18:05, 3 October 2011

Director, Act Designer

By Raffaele De Ritis

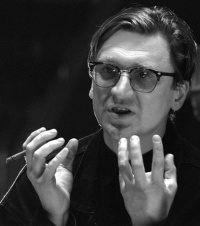

Born in Nizhny Tagil, Russia on December 20, 1951, Valentin Aleksandrovich Gneushev is one of the most influential circus directors-choreographers of the second half of the twentieth century, and the creator of some of the most innovative and celebrated circus acts of the 1990s.

As the “new circus” movement was drastically changing the traditional imagery of the circus (roughly between 1975 and 1995), Gneushev became the ultimate trendsetter, completely renewing the language of the ring. A master at discovering untapped talents in the disintegrating Soviet circus world, then creating and designing original acts for them, he eventually influenced the style of many young circus artists and companies, including Cirque du Soleil.

From Clowning To Directing

Valentin Gneushev fell in love with the circus as a teenager. He was fourteen when he began to perform in 1965 in a local Amateur Circus (the Russian equivalent of our Youth Circuses, albeit at a much higher artistic and technical level then in the West). He eventually decided to leave the Sverdlovsk Province and the industrial fumes of Nizhny Tagil (birthplace of the first Russian steam locomotive) and headed for Moscow, where he was accepted in the State College for Circus and Variety Arts (the “legendary Moscow Circus School”). There, he specialized as a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team..In Moscow, Gneushev studied under Roman Viktiuk, Firs Zemtsev, and especially Serguei Kashtelian, who had a lasting influence on his work. He graduated in 1978 and formed a short-lived clown trio with two partners, in which he revealed a special aptitude for pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., as well as a need to distance himself from the conventional circus clowning of the period.

An eager student of the arts (literature, history, painting, music), Valentin developed a remarkable artistic culture, and an aesthetic vision rooted in classic as well as contemporary art, and widely open to new influences—a far cry from the prevalent rhetoric of the Soviet artistic scene.

This eventually led him to study Movement Theater at the Moscow Theater Academy, and, upon graduation in 1980, to teach pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). and movement at the Moscow Circus School and other performing art institutions. His also embarked into intense theatrical activity, consulting in stage movement for several major theater productions of the period. In 1983, he was named Artistic Director of the Stage Circus group of the "Pravda" plant’s cultural center in Moscow.

Valentin’s work and interests led him to study at the GITIS institute, the theater institute in Moscow that was then developing new guidelines inspired by the “biomechanics” theory of Vsevolod Meyerhold—a sophisticated principle of body aesthetics spreading across mime, gymnastics and dance. Gneushev graduated as a director in 1986.

Although other director-choreographers applied with remarkable success Meyerhold’s principles to the circus (among them, Tereza Durova and Piotr Maistrenko), it fell upon Gneushev to transform them into a new mode of expression for the circus arts. Connecting the circus to a fundamentally different imagery, he developed new, groundbreaking circus aesthetics.

The Gneushev Era

By the mid-1980s, Gneushev’s activity became completely devoted to the circus. One of the very first acts he had created was, in 1983, The Moscow Builders, an extravagant, semi-ironic staging for Yury Odintsov’s perch pole act (an impressive but often boring Russian specialty), in which props and athletes evoked a tongue-in-cheek picture of proletarian street workers.

This act was perceived as somehow iconoclastic by the bureaucrats of SoyuzGosTsirk (the Soviet State Circus organization)—and their perception was indeed correct. But Valentin’s work was truly revealed to the world in 1987, when he introduced at Paris’ Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain the juggler Vladimir Tsarkov as The Red Harlequin, an act he had created in 1985.Inspired by Picasso’s "Arlequin" paintings, the act shattered the traditional juggler image and reconstructed the artist’s movements into a true choreographic piece, with its own vision and imagery. It became immediately clear that Valentin’s talent as an act choreographer was his ability to fully develop the hidden potential of a performer’s personality and combine it with his or her technical achievements.

Tsarkov’s success in Paris (he won a Gold Medal) didn’t truly please the Russian circus authorities, which were still promoting a more conservative and politically correct image of the Soviet circus. That same year, Valentin helped with the choreography of one of the greatest circus acts of all times, Vilen Golovko’s The Cranes, the superb aerial piece created by Piotr Maistrenko.

After his first success in Paris, Valentin returned regularly to the Festival, each time with new and always surprising acts, most of which became milestones of a new circus language. In 1986, he created to Nino Rota’s music the chair-balancing pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). of Vassily Demenchuk (performed since 2006 by Maxim Popazov). In 1989, it was the aerial strapsPair of fabric or leather straps used as an apparatus for an aerial strap act. act of Vladimir Kehkaial, the long-manned flying Hercules (whose style would inspire many subsequent strap acts), who became, with the clown David Shiner, the main feature of Cirque du Soleil’s Nouvelle Experience (1990)—the show that ultimately defined Cirque du Soleil’s artistic path. (Demenchuk was also featured in Nouvelle Experience).

That same year (1989), Valentin revamped the extraordinary tiger act of Nikolai Pavlenko, bringing the concept of acting and character to the big cage, and working on the trainer’s movements as if he were a symphony orchestra conductor, replete with baton, white tie, and tails. The result was astounding—a true ballet featuring seventeen tigers and their conductor performing to a piece of classical music. (Pavlenko has been awarded a Gold Clown at the International Circus Festival of Monte-Carlo in 1990.) 1989 also saw the superb juggling act on a rolling globe of Yury Borzykin.

Then came in 1990 the controversial Angel, with Aleksandr Streltsov—a near-naked child performing a sensual aerial strapsPair of fabric or leather straps used as an apparatus for an aerial strap act. act to Nina Hagen’s rendition of Schubert’s Ave Maria—and Rattango, the unconventional hand-balancing act of Genady Chijov, who partnered with a trained white rat. (Chijov eventually became the central character of Cirque du Soleil’s original production of Saltimbanco in 1993).

Cirk Valentin and Other Experiments

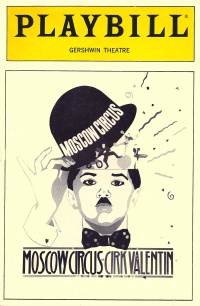

Finally, SoyuzGosTsirk began to include some of Gneushev’s acts in the foreign tours of the Moscow Circus companies, which attracted the curiosity of journalists and producers. One of these producers was Steve Lieber, who had organized very successful tours of the Moscow Circus in the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In 1991, Lieber launched a revolutionary concept: Cirk Valentin, a stage production displaying the best of Valentin’s acts, with Bobby Previte as music composer.

The show premiered in New York at the Gershwin Theatre, a major Broadway house, on November 6, 1991. It was choreographed by Pavel Brun, who had been for years Gneushev’s assistant and choreographer. Brun was to work later with Franco Dragone for Cirque du Soleil, and became the associate director of Celine Dion's show, A New Day, at Caesar's Palace in Las Vegas (2002-2007).Although it was not a commercial success and closed after a poorly attended two-month run, and its format was slightly controversial at the time—mostly because its production values were rather cheap for a Broadway show, which gave critics a misled reading of its concept—Cirk Valentin actually pioneered the subsequent trend of stage circuses, established the notion of authorship (or cirque d’auteur) in contemporary circus, and helped to definitely ascertain Valentin Gneushev as a name to contend with on the international circus scene.

The most spectacular feature of Cirk Valentin was a groundbreaking aerial bars act, Perezvony (Chimes), an impressively dark aerial piece performed to a symphonic piece by Valery Gavrilin, in which the performers evoked swinging bells. (Perezvony obtained a Silver Clown at the International Circus Festival of Monte-Carlo in 1993.) This act was later reproduced in Cirque du Soleil’s Alegria and Mystère productions, after Cirque du Soleil had hired Gneushev’s longtime associate, Pavel Brun.

Cirk Valentin also featured the balancing act of Yelena Fedotova and Anatoly Stykan, The Russian Barre act of The Zemskovi in its original version, as well as their perch-poleLong perch held vertically on a performer's shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. act, and an act especially created for the occasion, Charlie, a rola-bolaA board balancing on one or more cylinders piled on each other, and on which an acrobat stands performing juggling or acrobatic tricks. act inspired by Chaplin's The Tramp and performed by Serguei Loskutov and his son, Serguei, Jr. Other Valentine's creations were Gennady Chijov's Rattango,; Aleksandr Streltsov's Angel; the juggler on rolling globe Yury Borzykin.

For a few years, Gneushev continued to create acts for SoyuzGosTsirk, working in the organization’s illustrious Circus Studio in Moscow—where Piotr Maestrenko had built The Cranes and many other amazing aerial acts. But Paris’s Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain proved to be the platform on which Gneushev built his reputation and success. And after the fall of the Soviet Union, when individual Russian acts became available to the western market, many variety theaters and circuses, familiar with them though the Festival, began asking for “Valentin’s acts.”

In 1992, Gneushev worked with a new clown duo, Jigalov and Alekseenko. He reached the peak of his career in 1993-1995, probably his most prolific years, intensifying at this time his collaboration with music composer Lev Zemlinski. Valentin completely revamped the hula-hoop act of one of his protégées, Yelena Larkina, to the tune of Fata Morgana, with an Arabian theme; he created the wonderfully decadent “expressionist” juggling act, Votre Pierrot, for Evgeny Pimonenko; the very original slack wireA Tight Wire, or Low Wire, kept slack, and generally used for juggling or balancing tricks. act of Andreï Ivakhnenko; and The Little Devil for Anton and Leonid Beliakov.

Valentin also changed the staging of The Zemskovi's Russian Barre act with a Zemlinski’s score inspired by the imagery of Adam’s classic ballet, Le Corsaire—which would inspire a quantity of new Russian Barre acts. Likewise, the risley act he conceived for the Kurbanov Troupe in 1994, in which the performers, dressed as American bikers, used their motorcycles as trinkas, became one of the most copied acts of the contemporary circus. That same year, he choreographed the juggling duo Bondarenko as a true piece of sensual, contemporary dance. Finally, in 1995, Valentin and a selection of his acts went to Japan, as the centerpiece of Bunichiro Matsumoto’s short-lived Musical Circus, directed by Tandy Beal.

Final Bow: The Gneushev Studio

During the early 1990s, while Valentin’s acts were beginning to invade the best circuses and variety theaters of the planet, his base remained the Circus Studio in Moscow. But in spite of his numerous international awards and his obvious success, his artistic vision still contrasted with the politics of SoyuzGosTsirk (which, after the fall of the Soviet regime would be renamed RosGosTsirk). Still reveling on memories of its past glory, the old central circus organization seemed unable to truly appreciate the changes that their own Valentin Gneushev was bringing to the international circus scene.

Not surprisingly, in 1993, Gneushev decided to become an independent producer and began to attract young performers away from the State circus company, and to create acts for them that could be offered individually to the western market. Maxim Nikulin, son of the legendary clown and actor Yury Nikulin (1921-1997), who had succeeded his father at the helm of the "Old Circus" on Tsvetnoy Boulevard in Moscow (today Circus Nikulin) and had become one of the first Russian independent circus directors, offered Valentin a space in his circus to house the new Gneushev Studio.Not only did the Gneushev Studio become the main crucible of the post-Soviet circus experimentation, but Maxim Nikulin also expanded his association with Valentin, and asked him to stage two of his Circus’s productions, Sweet Love (1996) and Carnival (1997)—highly innovative and creative shows, as could be expected, which gave to the "Old Circus on Tsvetnoy Boulevard" a definitely new look.

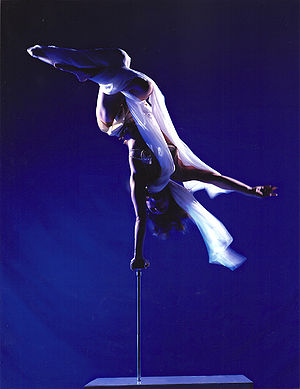

The Gneushev Studio continued to produce original acts, each completely different from the other, always investigating new artistic paths. The Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain again revealed the wonderful unicycle adagioAcrobatic act, generally involving a man and a woman, presented in a slow or romantic mood. of Diana Aleschenko and Yury Shavro (1996); the angular, neo-cubist hand-balancer, Aleksandr Veligosha (1997); and Valentin’s last creation, the superb hand-balancing act of Elena Borodina, inspired by Isadora Duncan. This last act was presented in Paris in 2001; by then the Gneushev Studio had already ceased to exist.

Valentin Gneushev had never been an easy collaborator. Fiercely individualistic, perfectionist, weary of all forms of authority, he didn’t fit within the old Russian circus community. He had little patience for the lack of culture of many of those who criticized him. His armor was the public persona he created for himself, a haughty cigar-smoking cultural snob, dismissing anyone who didn’t agree with him. Although his friends knew better, his attitude didn’t endear him to many around him, and he made indeed more enemies than he needed.

As the twentieth century ended, Valentin slowly took his interests away from the circus, turning to theater, movies, and television. Just as the new Russian government had finally recognized his exceptional contribution to the circus arts, making him "Art Worker Emeritus of the Russian Federation", he was burning bridges with the circus world. Sadly, his departing was of course the circus world’s loss.

Yet, ten years into the twenty-first century, many of Valentin’s best acts can still be seen in the best circuses and variety theaters of the world. They still impress by their amazing originality, their artistic perfection, and their unmatched creativity. Valentin’s influence spawned a plethora of new circus choreographers, who tried—a few successfully, many more, much less so—to shake up conventions and participate in the creation of a new circus language.

But Gneushev had a rule that some of his later successors often forgot: He used only highly skilled performers, who mastered their specialty. They were all superb technicians. Valentin never tried to compensate technical weakness with unconventional, eye-catching staging; on the contrary, he used the superior skills of his students to create a work of art that was unquestionably a true circus act—and therefore, unquestionably not a piece of dance or movement theater. He took remarkable circus performers and turned them into extraordinary circus artists. This was his true genius and will be the true legacy of Valentin Gneushev.

See Also

- Video: Vladimir Tsarkov: The Red Harlequin

- Video: Hommage à Léotard, Flying Act

- Video: Andreï Ivakhnenko

- Video: Johnny Gasser & Yury Kreer

- Video: Yelena Larkina

- Video: Yury Shavro and Diana Aleshchenko

- Video: Elena Borodina

- Video: Perezvony