Circus Sarrasani

From Circopedia

By Raffaele De Ritis

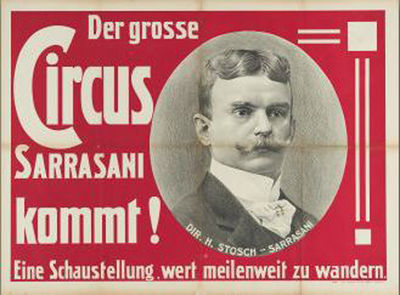

The legendary Circus Sarrasani was created in Germany in 1901 by a visionary clown and animal trainer, Hans Stosch (1873-1934). Sarrasani remains one of the most celebrated circus names in both Europe and South America. The title was alive throughout the entire twentieth century, under a succession of owners of more or less legitimate lineage. In circus lore, Sarrasani is still a fabled name that evokes a history of epic proportions with sociopolitical undertones, dominated (and occasionally brought close to bankruptcy) by the larger-than-life personality and extravagant vision of its famous founder, Hans Stosch-Sarrasani.

Contents

- 1 HANS STOSCH’S CIRCUS SARRASANI

- 1.1 From Hans Stosch To Giovanni Sarrasani

- 1.2 Zirkus Sarrasani

- 1.3 A Visionary Director

- 1.4 Sarrasani’s Zirkusbau: Circus-Theater der 5000

- 1.5 The Maharajah

- 1.6 Sarrasani in South America (1924-1925)

- 1.7 The Rise and Fall of The New Sarrasani (1926-1934)

- 1.8 Junior's Reformation Years (1934-1941)

- 1.9 Trude’s Reign: “Europe's Youngest Circus Director” (1941-1946)

- 1.10 South American Rebirth (1948-1972)

- 1.11 Epilogue

- 2 FRITZ MEY'S CIRCUS SARRASANI

- 3 Suggested Reading

- 4 See Also

- 5 Image Gallery

HANS STOSCH’S CIRCUS SARRASANI

Hans Stosch's vision, which came to full fruition in the late 1920's during the Republic of Weimar, shaped his circus as a paradigm of modernity and exoticism, which went far beyond the traditional approach of the major traveling circus families of the period. Stosch had a matchless ability to mix together industry, stagecraft, propaganda, literature, foreign politics, a specific style of circus management and circus aesthetics—as well as innovative techniques that stand today as milestones in the history of modern circus. His achievements influenced rivals such as Carl Krone, colleagues and admirers such as Jérôme Medrano and John Ringling North, and even, four generations later, Bernhard Paul.

From Hans Stosch To Giovanni Sarrasani

Hans Erdmann Franz Theodor Stosch was born April 2, 1873 in Lomnitz, a village in the Province of Posen, in Prussia (today part of Poland). He was the son of Albrecht Friedrich Stosch, a chemist and glass factory owner, and Hedwig Charlotte Catharina Stosch, née Ernst. Hans had five siblings: Marie Louise Albertine Walpurgis, known as Wally, born in 1868; two twin brothers, of whom little is known, born in 1869; Therese Edwig, born in 1971, who died soon after birth; and Elizabeth Friederike Erdmuthe, born in 1876. Hans’s mother died in 1884, when Hans was only eleven years old. Since at the funeral of their mother, only Wally, Hans, and Friedrike were present, one can surmise that the twins died in infancy.Hans was destined to succeed his father at the helm of the family glass business; it was not really his calling, and he proved to be a reluctant and rebellious student. Nonetheless, he was sent to study chemistry in Berlin, where he began to frequent assiduously the famous Circus Renz. There and then, Hans Stosch discovered that he was much more attracted to the circus than to chemistry or glassware. At Circus Renz, he had met the clowns Didic and Eugen Veldeman, and he decided to follow them as an apprentice.

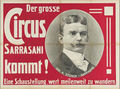

In 1888, we find Hans Stosch in the traveling circus managed by Helene Kolzer, the widow of Oscar Kolzer, a Bavarian equestrian and circus owner. There he performed as a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.-trainer—in white face in the manner popular at the time—working with small animals. In 1892, he adopted the exotic stage name of "Giovanni Sarrasani", for which he had found his inspiration in a novel by Honoré de Balzac, Sarrasine (1830): Its hero, Ernest-Jean Sarrasine, the son of a rich lawyer, leaves his bourgeois life to follow an artistic career against his father’s will. It is more than likely that Albrecht Friedrich Stosch didn’t approve of Hans’s choice to become a performer—let alone a clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team.!

In the following years, trade papers often showed ads for "Clown Sarrasani’s Happy Family": We learn that his act included monkeys, dogs, a goat, and a pig. Sarrasani appears to have had steady employment, and worked in leading circuses and variety theaters, from Saint Petersburg’s Circus Ciniselli to Madrid’s Circo Parish. In 1893 Hans Stosch married twenty-year-old Anna Albertina Augusta Maria Ballhorn (1873-1933), the daughter of a policeman. Together they would have two children, Hedwig (1896-1957) and Hans, Jr. (1897-1941), of whom later. Then, Hans Stosch had an epiphany that would change the course of his career.

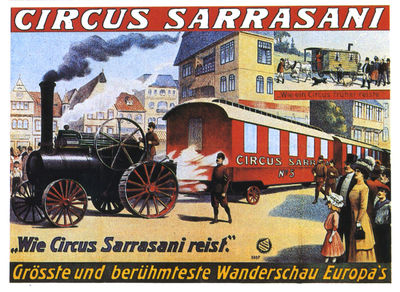

Zirkus Sarrasani

Up to the turn of the twentieth century, European circus directors and their companies rented the local circus building (unless they owned it) when they visited big cities, or they erected temporary wooden constructions in smaller towns that didn’t have a circus building. Circus companies traveling under canvas were few, small, and generally limited themselves to rural areas. Typically, you went to the circus; the circus rarely came to you.Then in 1897, the giant Barnum & Bailey Circus left the United States and began an extensive European tour that lasted until 1902. The immense assemblage of canvas tents, the swiftness of their setup and tear-down, the technical efficiency of the circus’s operations, the special trains on which it moved, the enormous big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) where hundreds of artists and animals performed on three rings simultaneously, the huge traveling menagerie filled with an extensive collection of exotic animals, all that made indeed a strong impression on the European public. It also impressed Hans Stosch.

Stosch decided to invest his savings (and his wife’s capital of 90,000 Marks) in a traveling circus under canvas. He found a partner in his old friend and fellow performer Robert Milde-Milton, and in 1901, they settled in Radebeul (a town in the suburbs of Dresden, in Saxony) to build their show. Hans Stosch was familiar with the area: His parents had lived in Dresden until the birth of Hans’s elder sister, Walpurgis, in 1868. In December, Stosch gave a foretaste of his show at the Apollo Theater in Brandenburg an der Havel, in the neighboring province of Brandenburg. The program consisted principally of acrobatic acts.

Zirkus Sarrasani hit the road in 1902, and made its debut in Meissen (of Meissen Porcelain fame), a few miles northwest of Dresden. The new circus was initially a modest affair, whose second-hand equipment had been bought from a couple of small French circuses and from the Dutch Circus Carré. The two-pole canvas tent was masked by an imposing façade, ornate with painted woodcarvings in the new and fashionable Jugenstil, the German Art Nouveau—a harbinger of things to come. Initially the only animals were horses, but a first elephant bought from Hagenbeck was soon added, and seven more would follow in 1906, purchased from the Leipzig Zoo. From the bankruptcy of Berlin’s Circus Renz (in 1897) came a full stock of spectacular costumes and uniforms.

A Visionary Director

Around 1905, Germany witnessed the rapid transformation of a few major traveling menageries into Europe’s largest tenting circuses: Charles (Krone), Barum (Kreiser), and Hagenbeck. Their owners had all been influenced by the European triumphs of Barnum & Bailey, which was the first circus to have traveled on the Old Continent with a vast, bona-fide menagerie. (To that German list can be added the Czech Kludsky, who also had its roots in the menagerie business.)Hans Stosch-Sarrasani (as he was now known) was the only one of this new breed of circus directors who had not been involved in the menagerie business (although he was indeed an animal trainer); yet he had been like them impressed by Barnum & Bailey’s combination of traveling circus and menagerie. He was also the first of them to grow, and his middle-class background and upbringing—wholly different from the traveling-entertainer milieu and education of most of his competition—informed his particular choices and aesthetics.

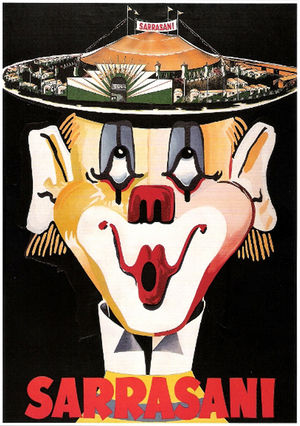

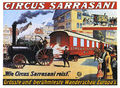

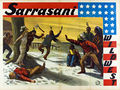

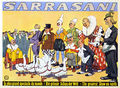

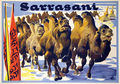

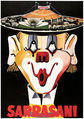

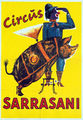

At the outset, Sarrasani gave special attention to the modernization of the traveling circus itself, following in that the technical and industrial progresses of his times: Already in 1903 he used a mobile power plant, announcing in his advertising: "The first circus ever with electric light". Another of his historical firsts was the use of steam-engine tractors to pull the circus’s rolling stock from the railway station to the circus lot. With his friend Max Friedländer (1880–1953), the son of the legendary Hamburg-based publisher and lithographer, Adolph Friedländer (1851-1904), Sarrasani developed beautifully designed American-style posters, establishing a new standard in the European advertising business; these posters were replicated in postcards and stickers that flooded the cities visited by the circus.

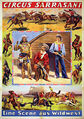

In time some extravagant features were added, such as the Circus’s own fire brigade, replete with a fire engine—and less extravagant ones, but quite novel and helpful in the traveling circus industry, such as a full press department, with its offices on wheels accompanying the circus. The high quality of Sarrasani’s programs and productions topped it all. National recognition came in Berlin, the capital of the German Empire, where Sarrasani erected a wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." on Schönhauser Allee for the 1906 Holiday Season.Proudly emphasizing his European identity, Sarrasani avoided the three-ring American format eventually adopted by some of his competitors. Yet, following the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West’s fifth European tour in 1906, Sarrasani’s show offered a "Wild West" spectacle that was widely publicized, Hans Stosch himself appearing in a cowboy outfit at press events. This theme, which would eventually become a Sarrasani fixture, had a German cultural relevance too: Wild West stories had been popularized in Germany by the prolific and extremely successful Saxon novelist Karl May (1842-1912), a Radebeul resident and friend of Sarrasani.

In 1907, Sarrasani was expanding his territory, conquering Prague, Brussels, Basel, and spending the Holiday Season in the old Circus Busch building at Vienna’s Prater. He also pioneered in Germany winter shows given in vast exhibition halls, as in Frankfurt in 1912, where he could accommodate 13,000 spectators per show. Zirkus Sarrasani was flourishing indeed and had become a force to reckon with. By 1910, Hans Stosch-Sarrasani felt financially strong enough to achieve his ambition: To have his own, state-of-the-art circus building. He first set his views on Berlin, where Circus Busch (Circus Renz’s successor) already reigned supreme, but met with too strong a resistance from the city—undoubtedly fueled by Paul Busch.

The easiest way was to build his circus in Dresden. The old Cirkus Schumann constructed toward the end of the nineteenth century in Löbtau, a suburb of Dresden, had been demolished in 1903 for safety reasons when Löbtau was incorporated into the city. Thus the road was free, and not only the City Fathers welcomed Sarrasani’s project, they were also willing to support it.

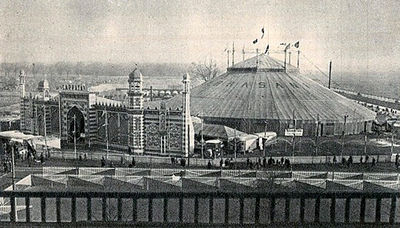

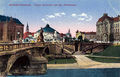

Sarrasani’s Zirkusbau: Circus-Theater der 5000

Already based in Radebeul, Sarrasani was well known in Dresden, where he was becoming a household name. The circus had often played Saxony’s capital in the past: The first time was in 1903, on Münchner Platz; then Sarrasani played on the Vogelwiese fairgrounds, and later on a piece of vacant land at Königin Carola Platz. It is this empty lot at Königin Carola Platz that the municipality of Dresden offered Hans Stosch-Sarrasani in 1910 to build on it a permanent circus.

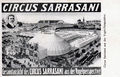

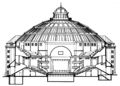

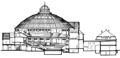

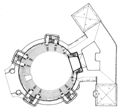

The 5,632 m2 space—a full city block—was located in Dresden Neustadt between Albertstrasse, Villierstrasse, and Briestrasse (between what are today Carolaplatz, Albertstrasse, and Sarrasanistrasse). It was sold to Sarrasani for the purpose of building a large circus that would correspond to the technical requirements of modern times and to the typical architecture of the city, and could be used also for large gatherings, musical performances, and other events. The price was set at eighty Marks per square meter (thus a total of 450,560 Marks, or about 5,700,000 Euros today). The deal was closed on May 27, 1910.The Dresden-educated and Munich-based architect Max Littmann (1862-1931), of the Heilmann & Littmann firm, who was at the time Germany’s most prominent theater architect, was hired to design the new circus. Heilmann & Littmann were put in charge of the construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.", along with more than twenty specialized firms; the work, which began immediately after the land purchase, came to completion on September 19, 1912. Advertised as "Europe’s most beautiful, largest, and most modern circus building", it was indeed a spectacular structure.

Towering at 36 meters (approximately 120 feet) above the ground, its huge cupola, 46.5 meters in diameter (approx. 151.5 feet), was free-standing, so that no supporting column impaired the audience’s vision—which was a significant architectural feat. The circus was equipped with a traditional circus ring, 13.5 meters in diameter, which could sink to reveal a water basin, on the model of Paris’s Nouveau Cirque. There was also a fully equipped stage behind the ring, approximately 10 x 10 meters with a height under grid of 17.5 meters and fronted by an orchestra pit. The height of the circus auditorium under cupola was 28.95 meters (approximately 90 feet).

The building prided itself on its advanced fire-safety features and numerous technical refinements—among which a steel cage for cat acts that could be pulled up under the cupola (a system that would be adopted after WWII by Paris’s Cirque Medrano). In addition to the dressing rooms, offices, and various rental spaces, the building housed a restaurant for the performers, an "American Bar" and another restaurant in the basement for the public, as well as three buffets-bars used at intermission. Behind the circus itself, a vast connected annex housed the menagerie and stables (which could accommodate 130 horses).

Although it was heralded as the "Circus-Theater der 5000", Sarrasani’s circus could actually accommodate 3,860 spectators—short of the number advertised, but impressive nonetheless. It was not, either, "Europe’s largest": Open in 1906, Paris’s Cirque Metropole, with its capacity of 6,000 spectators (a good portion of which stood in a promenade gallery) had indeed a claim to the title. However, the Cirque Metropole, too big and badly designed, was neither profitable nor successful, and was eventually demolished in 1930. Circus Sarrasani, on the other hand, was truly the world’s most modern circus building, and would be Europe’s (and the World’s) largest circus building after the Parisian circus’s demise; it would remain successfully so until the carpet bombing of Dresden by the British and American Forces in 1945.Dresden’s Circus Sarrasani was inaugurated on December 22, 1912 with a sumptuous show given in presence of the German Royal Family. A special souvenir program was printed for the occasion on white silk framed in green—the colors of Saxony’s flag, which would soon become Sarrasani’s colors for its fleet of vehicles. (At the time of the building's inauguration, Circus Sarrasani’s vehicles were still painted in red, an unusual circus color at the time in Europe, which became known in the circus community as Sarrasani red.)

In the Spring of 1913, the program was crowned by the presence of a group of authentic American Indians from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, headed by the old chief Two-Two (Edward Two-Two, 1851-1914). It just followed the first European "import" of American Indians by Hagenbeck in 1910. For the appearances of Two-Two’s tribe in the show, short Western movies were shot, and were projected on a screen on the stage between the acts. Sarrasani’s inspired press agents also created a national sensation by having the Indians making a pilgrimage to the grave of Karl May (1842-1912), the novelist who had popularized the American West stories in Germany and who had just passed away the previous year.

The Maharajah

In 1914 the touring unit, heading to Holland before trying his fortune in England, was stopped in its tracks by the storm of WWI. Performers from "enemy countries" were forced to leave, if not simply deported. Sarrasani, whose programs always contained vast contingents of Japanese, Russians and other "exotic" groups, tried to reach neutral Belgium, but found itself stranded in Essen, where its huge company had been reduced to 40 performers. Arranging a quick return to Dresden, Stosch saved his company's image with a typically opportunistic circus move.He called in circus librettist and director Adolf Steinmann, the creative mind behind Berlin’s Circus Busch’s legendary pantomimes, to stage patriotic spectaculars in Dresden’s circus building. The first one was Europe in Flames (1914), followed each year by pantomimes of a similar vein up to 1918. (Some of Sarrasani's pantomimes, such as Torpedo... Los! in 1918, were also presented at Circus Busch.) The traveling unit, with its important menagerie, tried to survive in neutral countries—such as Denmark where, in 1915, an event was to inform Sarrasani’s future aesthetics: A collaboration with the celebrated Nordisk Film company, famed for its cinematic theatrical storytelling: "...an aesthetic system, based on the idea of the shot as a rich totality… " (David Bordwell).

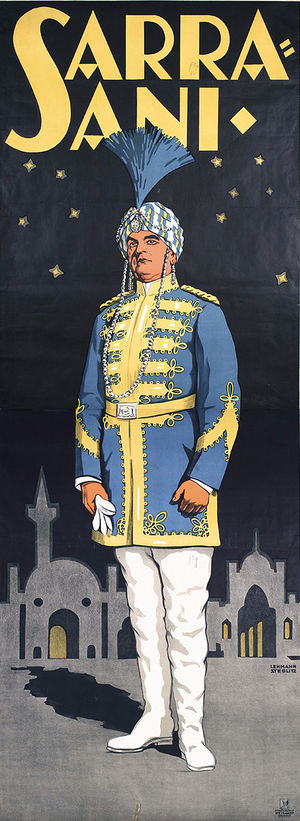

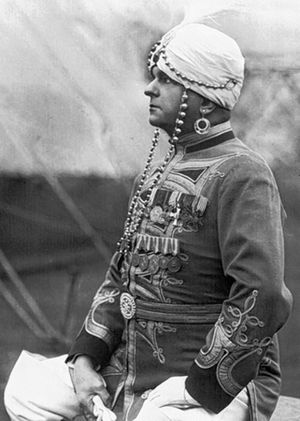

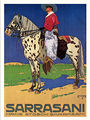

Nordisk Film employed the circus's elephants, zebras, and camels in a few shots for Robert Dinsen’s oriental melodrama The Maharajah’s Favorite Wife (Maharadjahens Yndlingshustru, 1917). The Maharajah’s outfit worn by its leading actor, Gunnar Tolnaer, apparently left such strong an impression on Hans Stosch-Sarrasani’s imagination that, in the ring, he would switch after the War his trademark cowboy outfit for the elaborate costume of a Marharajah—certainly more attuned to his newly reached status of "Zirkus-König" (Circus King).

Thereafter, and until his death, Hans-Stosch Sarrasani would be known in the circus world as The Maharajah. It is in a Maharajah costume, replete with elaborate turban and jewelry, that Hans Stosch-Sarrasani would henceforth present his huge elephant act, and appear on advertising photographs and posters. (In 1921, Sarrasani's vast menagerie was used again for an exotic German film classic, Das indische Grabmal (The Indian Tomb, 1922), featuring Conrad Veidt as a Maharajah.

Back in Dresden in late 1915, while the circus survived with its patriotic pantomimes, war shortages almost destroyed its menagerie: elephants and exotic animals were used by the army for transport, and most of the wild animals in the circus’s vast zoological collection died or had to be killed. And then, after the war was lost in 1918, Germany was hit by a galloping inflation; by the early 1920s, it made it impossible for the giant circus to sustain a tour with its big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) and all the necessary equipment. Sarrasani, with a large contingent of performers who had escaped the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, barely survived by performing either outdoors, on theatre stages, or in large halls (like in Frankfurt in 1921, where Alfred Schneider and his famous group of 70 lions topped the bill).

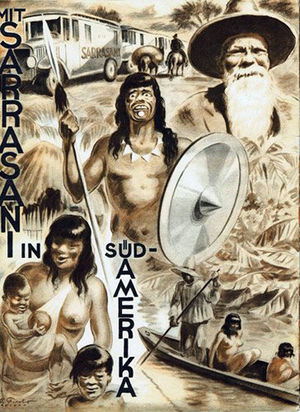

Sarrasani in South America (1924-1925)

In spite of these efforts, Sarrasani was facing bankruptcy. Hans Stosch had previously met one of Germany’s most powerful men, the industrialist Hugo Stinnes (1870-1924). A member of the Reichstag, who went down in German history as "The Inflation King" for his war and post-war profiteering, Stinnes had large interests in several key areas of the German economy (as well as significant international investments); he would eventually control some 4,500 companies, ranging from mines and energy to mass media, and had developed an important transatlantic shipping company (which still exists today) during the war years. Stosch made a deal with Stinnes, who accepted to fund a South-Amercian tour of Circus Sarrasani.Shipping a full German circus to the New World, and sponsoring its tour, was to Stinnes a good strategic move in several ways: It was good advertising indeed for his shipping company, and a good opportunity for German propaganda in South America; his press empire could easily transform the tour into a major national event. Not fortuitously, Sarrasani converted his circus vehicles for road transportation (the circus originally moved by rail), a change that would promote the innovative German automobile industry at home and abroad. Not to be forgotten in this scheme was Stinnes’s ownership of large tracks of land in South America, and his control of Argentina’s largest oil concession: South America was undeniably important to his, and Germany’s, business interests.

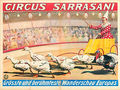

On November 4, 1923 in Hamburg, three of Stinnes’s steamships, Danzig, Ludendorff, and Tirpitz, loaded with "120 vehicles, 200 animals and 300 persons" (according to press releases), set sail for Brazil. After one month at sea, Circus Sarrasani landed in Rio de Janeiro, where the circus, set up in the very center of city, began what was to be a triumphal journey. It continued through São Paulo and a few major Brazilian cities, then to Montevideo (Uruguay), and eventually visited Argentina, where it opened in Buenos Aires in April of 1924.The circus Hans Stosch had taken to South America was not as important as the pre-war Circus Sarrasani, and its show was neither as big nor elaborate, but it was very respectable by any European standards, with many group acts and large "exotic" troupes filling the ring. It was crowned by Hans Stosch-Sarrasani’s big elephant act, which was undoubtedly the largest ever seen in South America. The Reinsch Troupe of jockeys, the clowns Babusio, the Lorch Family’s famous risley act, the Rikoku Japanese family (a Sarrasani fixture for many years), and The Artonis on the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze) topped the bill, as well as Tilly Bebé’s famous lion act that appeared at the beginning of the tour only, before returning to Germany due to personal disagreements with the circus’s management.

There were a few "exotic" tableaus, as was then the fashion in German circuses and especially at Circus Sarrasani; an oriental display featured Sarrasani’s corps de ballet, the Ben Saïd troupe of Moroccan tumblers, and a group of camels, zebras and other exotic animals. During intermission, a swaypoleA high, flexible vertical pole (originally made of a single piece of wood, and today of fiberglass) atop of which an acrobat performs various balancing tricks. act performed outdoors (a good publicity for the passersby), and beside the menagerie, one could visit a sideshow of "female oddities" such as a bearded lady, a fat woman and a "hermaphrodite", which were advertised "For Adults Only"…

It was at any rate a much more lavish and spectacular show than anything that was usually seen in South America at the time, and it met everywhere with tremendous success. In Argentina, local performers acting popular comedies and dramas in the ring were added to the circus fare. Sarrasani’s tour had political undertones: State and local officials greeted the circus and attended the show in their official capacity, and the German's president, Friedrich Eberd, had heralded Circus Sarrasani as a "German Cultural Ambassador".

From Buenos Aires, the circus caravan visited Rosario, Santa Fé, and Cordoba, before finally returning home in 1925. Sarrasani’s remarkable Press Department Director, the well-known journalist and writer A.H. Kober, had followed the South American tour, feeding continuously the German press with stories and pictures of the circus’s exotic adventures—and he would continue to exploit the subject in the circus’s own magazine for years afterwards. At home, Hans Stosch-Sarrasani was not only far from forgotten, he had become a living legend!

The Rise and Fall of The New Sarrasani (1926-1934)

Circus Sarrasani reached its pinnacle, and made its most significant contribution to circus history, in the second half of 1920s. Upon his return to Germany, Stosch reinvested the fortune ha had made in South America into a total revamping of his circus—with a sharpness of vision unique in circus history, which encompassed artistic, technical, and organizational aspects.

The circus was partially motorized (the horses and large animals still traveled by train), and was advertised as an “Automobile-Zirkus”—whereas all German major circuses traveled exclusively by rail. About 200 transport and habitation wagons, pulled by Mercedes-Benz trucks, were elegantly painted in white and green (the Saxon flag colors), with the two colors parted diagonally—a very unusual color scheme and design that would become intimately associated with all things "Sarrasani". The name SARRASANI was displayed on the flanks of every vehicle in embossed brass letters.

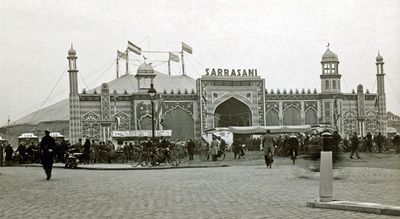

Reflecting the new "oriental" character of its legendary owner, the giant big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) was fronted by an extravagant oriental façade (soon copied by Sarrasani’s major competitors): Designed by the architect Alfred Pape, it extended over 60 meters (198 feet), and was 15 meters high (49½ feet); its width could be reduced if needed by suppressing various panels or turrets. By night the monumental façade, looking like the fabled palace of the Maharajah of Mysore on a celebration day, was illuminated by thousands of light bulbs. Like the green and white color scheme of its rolling stock, this façade became an iconic feature of Circus Sarrasani.

This aesthetic revamping affected the show too. Still avoiding the three-ring, post-Barnum format adopted by his major competitors, Sarrasani had nonetheless a huge cast of performers, including many troupes, not to mention his own group of elephants that had reached 22 heads. According to a 1927 press release, the ring had been enlarged to a diameter of 17 meters, although such a ring never existed: It was in fact the total diameter of the circle that comprised the ring and the empty space surrounding it, which was used for parades and large displays of performers, either two- or four-legged.

Beside the traditional circus acts, the show included troupes of American Indians, Argentinean gauchos, Moroccan tumblers, Chinese acrobats, Japanese jugglers, Singhalese dancers, a corps-de-ballet, two orchestras, a cornucopia of exotic animals and horses, which all contributed to the one-ring, Wagnerian utopia of a "total experience" Stosch described as "not a circus, but a new World Theatre". Part of Sarrasani's circus revolution was to stay away from the American-style three-ring circus, which was still popular in Germany, and to put the emphasis on the traditional circus format in its own magnitude.In 1927, Sarrasani inaugurated in Chemnitz a huge winter-circus construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.", named Winterbau Irigoyen in tribute to Hipólito Irigoyen (1852-1933), the Argentinean president who had remained neutral during WW1. It was another marvel of engineering: 8 steel poles, 25-meter high, supported a 20-ton octagonal wooden cupola to which the wooden frame was attached, extending to a first circle of 25 connected wooden-poles and then to the wooden side poles at the perimeter; the ensemble formed a huge structure with a diameter of 78 meters (277 feet)—certainly the largest circus construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." ever built. The cupola, the frame, and the sidewalls were covered with canvas. The frame was built in such a way that it had neither nails, nor screws: It was holding together with mortises, grooves, and tenons. The construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction.", which took two weeks to erect, replaced the tent for the winter dates, and was heated with hot air blown under the seating system. It could accommodate 10,000 spectators, and elaborate interior decorations transformed the house into yet another lavish oriental palace.

Unfortunately, Circus Sarrasani’s Golden Years didn’t last long. Sarrasani had faced a serious problem when he returned to Germany: During his absence, he had lost his grasp on the home market. His principal rival, the giant Circus Krone, had become in the interval Europe’s largest circus, and was now a household name in the country and a power to reckon with. The two giant circuses were fighting fiercely for territory. It was costly, and Carl Krone and Hans Stosch-Sarrasani eventually met and agreed to coordinate their tours. But things didn't go so easily with more hungry and aggressive rivals such as Strassburger, Barum-Kreiser, and Gleich.

Eventually, the economic crisis of 1929 brought Circus Sarrasani to the verge of collapse. Stosch pleaded his cause with the Saxon government, asking for subventions or tax relief on account of his circus being a "national heritage". This didn’t work, so he tried to find success out of Germany: In 1930 a French tour attempt was cut short in Strasbourg, where the circus faced anti-German propaganda; a foray in Switzerland was interrupted by a mortal street accident involving some of the circus’s vehicles. Sarrasani didn’t fare better in Holland and Belgium: In Liège, anti-German protesters became violent and shows had to be cancelled. Finally in January 1932 in Antwerp, the circus was partially destroyed by a suspicious fire.

Sarrasani attempted a new tour in Holland in the spring of 1932, and then decided to settle in the Dresden building for the 1933 season. The rising National Socialist party had not found a collaborative friend in Hans Stosch-Sarrasani: he had steadfastly refused to rent his building for Nazi political rallies. Adolf Hitler’s accession to power in 1933 didn’t make things easier, and Circus Sarrasani was soon labeled as a Jüdenzirkus ("Jews’ circus") for the presence of Jewish employees and artists on its roster. To make matters worse, Stosch’s wife, Maria, passed away that same year.Circus Sarrasani was now a shadow of the powerhouse it had been just a few years earlier. Finally, Stosch decided to return to South America. His trip to Rotterdam, where the circus was scheduled to embark in the spring, was transformed into yet another dispiriting visit to Holland: In Amsterdam Sarrasani, a Jüdenzirkus in Germany, was labeled a "Nazi circus"! All the same, the circus reached Rotterdam and Sarrasani set sail again for Brazil on April 13, 1934 (a Friday)—helping in the process many Jewish performers and workers and their families to leave an increasingly inhospitable Europe.

Sarrasani arrived at Rio de Janeiro on April 29. A couple of weeks later, on May 14, 1934, the giant circus opened at the Esplanada do Castelo, in the center of Rio. Circus Sarrasani was back on friendly territory, and success returned at last. During its stay in São Paulo, "Junior", as Hans Stosch, Jr. was known, told his father that he intended to marry a twenty-year old Swiss dancer from the company, sixteen years his junior, Gertrude Helene Kunz (1913-2009), nicknamed Trude; although this decision would have a decisive impact on Circus Sarrasani’s fate in years to come, the Maharajah was not particularly pleased. Hans Stosch-Sarrasani, now sixty-one, suffered from a bad heart condition; he was exhausted and his health began to deteriorate. In late August, while the circus was still in São Paulo, he had to be hospitalized. Then, in the night of September 20, 1934, the legendary circus Maharajah departed for the nirvana.

Junior's Reformation Years (1934-1941)

Hans Stosch never made a will. He was survived by two children. Hedwig, the elder (1896-1957), had left the circus to marry an engineer in Hamburg. The younger, Hans Junior, was born on February 15, 1897 in Sorau, in East Prussia (today’s Zary, in Poland). After volunteering during WWI to serve in Saxony's Hussars, he had studied business and had been gradually integrated into the circus organization. He was therefore the heir apparent. Upon his father's death, Junior inherited a company ridden with debts, and the Nazi government of Dresden was considering an appropriation of Sarrasani’s circus building, in part motivated by Hans Stosch-Sarrasani’s earlier attitude toward the Nazi Party. Under Junior’s reign, significant changes would come that would transform Circus Sarrasani artistically, organizationally, and politically.In late 1934, Junior flied back to Germany to meet the new Reich’s powerful Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels. The Reich was already supporting the circus; it sponsored Hagenbeck’s international tours, which were good for German propaganda, and Circus Busch, considered a Berlin institution. Junior didn't want to miss the opportunity to include Circus Sarrasani into the fold. Gifted with a cunning diplomatic talent, he proposed a restructuration of his circus in two points: (1) Sarrasani should be protected and used as a symbol of national pride; (2) the artistic concept of the circus and its logistics would be readjusted to solve its financial troubles.

A financial help was approved on the condition that a "renewal" (i.e. a racial purification) of the circus’s employees was considered too. Junior agreed. He returned to Brazil with a 150,000-Mark government subsidy and began to deeply alter his father's dream. Circus Sarrasani had entered the realm of legends for its rich artistry, its sheer magnitude, and the perfection it brought to every detail; Junior downsized the circus to a lighter structure, able to play smaller towns where it could stay for shorter periods, and the show was simplified, evolving into a more traditional and less adorned succession of acts.

The change didn’t hurt Sarrasani, which continued its successful Brazilian tour, and then moved in 1935 to Uruguay. There, a succession of railroad accidents and storms damaged the circus, but the German government proved supporting, always ready and willing to help Sarrasani out of its troubles. The circus continued to Argentina where, on April 13, 1935 in Buenos Aires, Hans Stosch-Sarrasani, Jr. finally married Trude Kunz. Things were looking good for Junior.

Argentina was now under a pro-Nazi dictatorship (Argentina’s "Infamous Decade"), and Junior had to pay the price for his coziness with the Nazi regime. On Labor Day, May 1 1935, he was requested to decorate his circus with an assortment of Nazi flags and symbols to celebrate the German-Argentinean alliance. It was to be the first of several propaganda events hosted by Sarrasani in that country. The Argentinean President, Augustín Pedro Justo, cited Circus Sarrasani and the airship Graf Zeppelin as "two examples of the German genius". Meanwhile, business was going well, and Junior invested in some land properties in Argentina.He returned to Germany at the end of 1935 with part of the original circus equipment, leaving in Argentina a fully operational South-American unit under the management of his collaborator, Josef Bamdas. Junior reopened in Dresden in December 1935 with a classic circus program. In the following years, especially during WWII, performers would be principally German or Italian (as in the other German circuses and variety theaters during that period), and the workers were Czech or Polish. In 1936, the government offered Sarrasani to play Berlin during the Olympics: Berlin’s own Circus Busch had been closed and was set to be demolished to leave room for the future development of Albert Speers’ utopian Reich capital.

Then, the Argentinean unit returned to Europe, and Junior found himself at the helm of three circus units: the circus in Dresden for the winter season, the touring unit (with a lighter version for small towns), and another unit for foreign tours sponsored by the Reich, which performed either under the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), in circus buildings, or in theaters. Thus Sarrasani visited Czechoslovakia, Holland, Belgium (including Brussels's Cirque Royal during the winter of 1937-38), and Wien and Austria in 1938.

With the advent of WWII, the building in Dresden began to stage several circus pantomimes on propagandist themes, such as a celebration of the Spanish Civil War, or the famous Nena Sahib (1941), which celebrated India’s autonomist fight against England, co-produced with Paula Busch. If those were relatively profitable years, things were not always easy for Junior, and it intensified with the War: He not only still had to deal with the debts left by his father, but also with intense government oversight and its permanent suspicion, its many demands, and the incertitude that surrounded the organization of his circus tours, as well as an increasing shortage of performers.

In 1941, after the cancellation of a planned tour in Hungary due to the Hungarian attack on the Soviet Union in Ukraine, the circus was allowed to play Berlin again for a long engagement. Junior organized that engagement in the greatest possible style, reminiscent to some extent of Sarrasani’s past grandeur. But on July 9, 1941, a few days before the opening, he died suddenly of a cardiac arrest in his room at Berlin's Hotel Excelsior. He was only forty-four, but he was in poor health due in good part to a serious problem with alcoholism. His body was cremated and his ashes buried next to his father's at the Urnenhain Tolkewitz Municipal Cementary in Dresden-Tolkewitz.

Trude’s Reign: “Europe's Youngest Circus Director” (1941-1946)

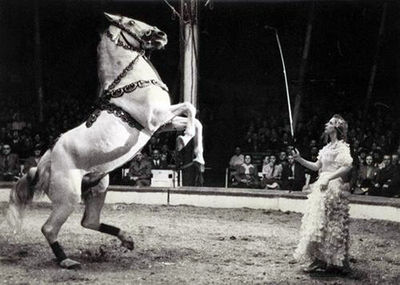

Once again the circus was suddenly left without a director, and Trude Stosch-Sarrasani, Junior’s young widow, took over. Born in Vevey, Switzerland, on January 18, 1913, she had joined the circus for its 1934 South American tour as a dancer with the Alois Escamillo Ballet. In the last few years, she had proved her abilities as a manager and a shrewd diplomat. She had organized the return of the Argentinean unit to Germany, and she had led many negotiations with Goebbels and the Propaganda Ministry for the organization of the circus’s tours, or to solve various problems of political nature, filling in for her increasingly unreliable alcoholic husband.At twenty-eight, Trude was now the youngest circus director in Europe, a fact that was duly advertised. She successfully completed the Berlin engagement, and then took the circus on its previously planned Hungarian tour. A performer at heart, and probably following the example of her illustrious father-in-law, Trude quickly built a circus promotion based on her personality, her portrait appearing on posters, program covers and magazines, and she established her presence in the ring with a liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. horse act prepared by Sarrasani’s famous Master Equestrian, Carl Petoletti. She also proved a compassionate director, caring for her employees whose conditions were rather tough during the disastrous final years of the War.

As touring with the circus in war-torn Germany became increasingly difficult, Trude gave a new impulse to the Dresden building, transforming it into a circus-varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s., Sarrasani-Haus. In that she built upon the vogue of German "varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s." shows, which mixed bona-fide circus acts (including large animal acts) with traditional vaudeville fare, exemplified notably by Berlin’s famous Wintergarten and Plaza theaters. Sarrasani’s programs were renewed every two weeks, with some of the best acts of the period on the German circuit: Charlie Rivel, Maria Valente and many other stars of the variety circuit appeared at Circus Sarrasani.

Trude also produced revues such as Gloria Express and Alles fürs Herz (All for the Heart). For the winter season, the building reverted to classic circus fare. In 1944 she was still able to produce an ambitious circus musical based on her own life: Durch die Welt im Zirkuszelt (Around the world under a big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau)), for which she invested liberally in talent, music, choreography, costume design, and scenic innovations. Meanwhile, Trude had acquired a close collaborator and a new partner in her life, the Hungarian aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc. Gabor Nemedi, whom she had met when he worked at Circus Sarrasani with his flying casting act, The 3 Turuls.

At the threshold of 1945, Germany had all but lost the war; the country was in a desperate situation, encircled by the advancing Allies’ troupes, and trying to survive under incessant bombings. Trude took most of the circus equipment away from Dresden, to the village of Prossen on the Elbe River, and booked her horses, elephants and trained hippo with Circus Knie, in neutral Switzerland. Amazingly, the all-powerful Nazi administration was still functioning and working zealously; they sued Trude for "protecting strangers" and other "crimes against the Reich", while the Gestapo arrested Nemedi. Then, on the evening February 13, 1945, Dresden was practically destroyed in one of the most terrifying and senseless aerial raids in war history. The magnificent Sarrasani-bau, the world's largest circus building, was hit during a performance and collapsed in flames. Many lives, human and animal, were lost in the catastrophe.Trude and Nemedi (who had escaped the Gestapo in the ensuing panic), quickly headed for Czechoslovakia, where they found refuge in Circus Kludsky's winter quarters; then to escape the imminent Soviet invasion, they fled to southern Germany. At the end, Trude lost everything: the equipment stored in Prossen disappeared, including the legendary circus façade. Some of the equipment left in Dresden that had survived the destruction was used for a temporary unit of Leipzig's Circus Aeros; the old big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) went to Berlin to Paula Busch.

The Soviet occupants considered the animals Trude had placed in Switzerland as "patrimony of the German State". Four of the elephants and the hippo were given to the Knie family as indemnity for their upkeep expenses. (Under Rolf Knie, Sarrasani’s elephants set in motion one of the most important chapters in the history of elephant training.) Other elephants were bought by Darix Togni in Italy. Trude, now labeled as a "Nazi collaborationist", had a hard time to find work.

She was finally able to put together a high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) act, while Nemedi built a new aerial act, and by1946, they began to find work in German circuses: Schulte, Hollzmuller, Franz Althoff, Apollo-Schikler. In 1947 they went on tour with their own, newly-created small circus, Circus Europa. But life was uneasy for them in post-war Germany. The couple began to test their South American contacts with the hope to go back to Argentina. In January 1948, after a winter engagement at Paris's Cirque d'Hiver, Trude and Gabor finally fled to Buenos Aires.

South American Rebirth (1948-1972)

Juan Perón had been elected President of Argentina a couple of years earlier, following a period of military dictatorship. Even though he promoted a policy of social justice and economic independence, Perón, who had in the past professed his admiration for the achievements of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, established a quasi-dictatorship. That, added to the close ties Argentina had long established with Germany, made it easier for Germans tainted by a Nazi or pro-Nazi past to find refuge in a country that already had a large community of German origins.

Two former Argentinean Sarrasani employees, Ismael Pace and José Lectoure, were managing at the time the Circo Shangri Lá in Buenos Aires's Parque de la Ciudad, a popular amusement park. They offered an engagement to Trude and Gabor. The reunion led them to reorganize their enterprise, which took the name of Circo Shangri Lá-Sarrasani. Juan Perón and his wife, Evita, attended the new concern’s grand opening on April 28 1948. Trude's talent for politics and diplomacy was not lost, and she developed a good relationship with the Peróns. In 1950, Evita bestowed on Trude’s circus the title of "Circo Nacional Argentino".

In 1952 the Parque de la Ciudad had to be demolished to make room for urban developments. Evita's death that same year was another blow for Trude. She was nonetheless able to put together a traveling show, titled Gran Circo Sarrasani, with which she went on tour in Argentina, Brazil, Chili, and Paraguay. Then, in 1955, a military coup toppled Juan Perón’s and his regime. Trude, who had been a little too cozy with the Peróns to feel comfortable, headed for Brazil, where she still owned some real estate and properties acquired before WWII, including a Sarrasani warehouse.In the spring of 1958, she erected in Rio de Janeiro one of the weirdest circus structures ever: a circular aluminum dome, a sort of flattened bell dubbed El Palacio de Aluminio. Needless to say, even in the austral winter, the "palace" was a hothouse! It was then erected in São Paulo, where Trude eventually rented it out for other uses. Trude’s father passed away in Buenos Aires at that time. On her way to the airport, she learnt that a fire had destroyed the structure and, apparently, its tenants didn’t carry an insurance. It was one blow too many, and Trude finally decided to retire in her Argentinean property of San Clemente del Tuyú, near Buenos Aires.

Then, in 1968, she got involved in another, even crazier project: An Argentinean engineer suggested to erect a circus in Buenos Aires made entirely in plastic and polyester. Trude brought artists and animals from Europe but, close to the opening day, a measurement mistake made it impossible to put up the pieces of the structure together... The plastic circus never concretized—although Trude kept its façade, which she eventually used later. Billed as Revista Sarrasani, the new show finally opened in a theater, and then went on tour in Argentina under the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) of the Segura circus family, fronted with her plastic façade.

Finally, in 1972 Trude, now fifty-nine years old, decided to go back into retirement and parted with the Seguras—who went to Brazil where they toured under the title Circo Real-Madrid. The original Circus Sarrasani created by the visionary Hans Stosch and maintained alive against all odds by Hans Stosch-Sarrasani, Jr. and (mostly) by Trude Stosch-Sarrasani had ceased to exist.

Epilogue

Trude had not returned to Europe since 1948, although she never lost her European contacts. In the late 1950s, she become implicated in a three-year legal battle with an old employee, Fritz Mey, who had opened his own Circus Sarrasani in Germany in 1956. (See below, “Fritz Mey’s Circus Sarrasani”.) In 1975, she accepted an offer from a horse training center to come to Germany; they wished to put Trude back in the circus ring with one of their horse acts. Nothing actually came of it, and it was finally Fritz Mey who hired Trude for his new Circus Sarrasani, to present a liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act prepared in Italy for her by Enis Togni.

Trude was sixty-four years old at the end of the 1977 season; she decided to retire definitely and returned to Argentina. At same time, a small illegitimate Circus Sarrasani made a brief appearance in Argentina in 1976; it was run by the Zinnecker-Werner family of animal trainers, who had been Trude's employees. (It re-emerged shortly in Germany in 1989.) Meanwhile, in 1976, Trude had officially adopted Mey's companion, Ingrid Wimmer, who took the name of Sarrasani. Mey and Ingrid had had a son, André, who thus became the legitimate heir to the name.Gabor Nemedi, Trude's long-time companion, passed away on March 31, 1981 in Buenos Aires. In the early 1990’s, after the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989), the authorities in Dresden began to recognize Circus Sarrasani as a local heritage, and organized various ceremonies and exhibitions. In 1991 they inaugurated a Sarrasanistrasse (Sarrasani Street) where the circus building had once stood, replete with a commemorative plaque and an elaborate "Sarrasani Fountain"; the following year, Trude Stosch-Sarrasani was invited as a guest of honor to a Sarrasani Day celebration, and she returned to Dresden for the first time in nearly half a century. The Stosch-Sarrasani family grave was named a national monument. In 1996, another Sarrasanistrasse was inaugurated in Radebeul, where Hans Stosch had lived and started his circus, and the town had Hans Stosch-Sarrasani's home repainted as a memorial to its legendary owner.

Trude died on July 6, 2009 at age ninety-six in her home at San Clemente del Tuyú, a seaside resort near Buenos Aires. She was saluted by the Argentinean and Brazilian press as the Grande Dame of the Circus: She had indeed become a household name in South America—and to some extent, she had superseded there her illustrious father-in-law, Hans Stosch-Sarrasani, the Maharajah himself, as the person most readily associated with the name of Sarrasani and all what it meant.

In 1998, Trude had ceded the South American rights to the Sarrasani title to a close friend, Jorge Bernstein, a Buenos Aires businessman—an architect and entrepreneur who had developed several shopping centers, as well as revived the Tattersall de Palermo, an plush entertainment hall in the old hippodrome of Buenos Aires. Through press conferences and newspaper articles, Bernstein relentlessly stressed the importance of Sarrasani’s heritage, and announced several important projects over the years, which never materialized: A permanent circus building, a new big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau), a theme park, an equestrian show, a TV series, a circus festival…

Finally, he produced a Sarrasani Varieté-Gourmet at the Tattersal de Palermo in 2013—a dinner-show in which he presented Graf Story, the show conceived by the Russian comedy-magician, Evgeniy Voronin, with a remarkable ensemble of award-winning European and American circus acts. On the other side of the Atlantic, in Dresden, the name is kept alive with another dinner-show, André Sarrasani’s Sarrasani Trocadero. Yet at the time of this writing (2014), a true Circus Sarrasani has not been revived either in Germany or in Argentina since the demise of Fritz Mey’s “neo-Sarrasani."

FRITZ MEY'S CIRCUS SARRASANI

In 1956, a new Circus Sarrasani appeared in Germany. It had no direct connection with its founder, Hans Stosch-Sarrasani (1873-1934), or with the latter’s heiress, Trude Stosch-Sarrasani (1913-2009). Yet its creator, Fritz Mey (1906-1993), was a former collaborator of Hans Stosch-Sarrasani; after Trude’s exile to Argentina, he decided to revive Circus Sarrasani in Germany, and became in the process one of the most respected European circus directors of the 1960-70s. He also became the person longest associated with the name Sarrasani. After his retirement in 1979, the circus was taken over by his life companion, Ingrid Stosch-Sarrasani, née Wimmer, and then by their son, André Sarrasani. Regular tours stopped after 2000, and a true Circus Sarrasani, Stosch-owned or not, sadly ceased to exist.

Fritz Mey

Fritz Mey was born in Crawinkel, in the eastern German province of Thuringia, on June 5, 1906. He was the son of the head carpenter for the Gerhardt Company, which was at the time a leading manufacturer of circus and fairground equipment. Hans Stosch-Sarrasani, Circus Sarrasani’s founder, had become a client of Gerhardt in 1904. In 1919, when he was fifteen years old, young Fritz met Hans Stosch when he helped his father deliver a new seating system for Sarrasani. As legend has it, a storm suddenly developed, and Fritz helped secure the big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). His understanding of tent rigging impressed Stosch, and soon after, Fritz went to work full-time for the legendary director.Fritz Mey would be part of Circus Sarrasani’s 1923 and 1934 South-American tours. In 1926, he was a key participant in the conception of the revolutionary seating system for Circus Sarrasani’s new, giant big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau). At the time of Hans Stosch-Sarrasani's death in 1934, Mey had developed a close relationship with Hans Stosch-Sarrasani, Jr (1897-1941), known as "Junior", and he became prominently involved in the management of the circus. After Junior's untimely death in 1941, Fritz Mey and two other circus employees are said to have conspired against Junior's wife and successor, Trude Stosch-Sarrasani, contacting Joseph Goebbels, the powerful Minister of Propaganda who oversaw all German entertainments, in an unsuccessful attempt to take control of the circus.

His alleged scheme having failed, and with WWII now in full bloom, Fritz Mey enrolled in the Wermarcht. At the end of the conflict, he found himself in East Germany, in the Soviet zone. In 1950 he managed to return to West Germany and worked for a while with the growing Circus Franz Althoff, then managed the tour of Eisballett, a circus-themed ice revue presented under a big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) and led by the former figure skating Olympic champions, Maxi Herber and Ernst Baier.

The "New" Sarrasani

In 1955, Fritz Mey approached Hedwig Stosch-Brandt (1896-1957), Hans Stosch-Sarrasani’s elder daughter, who had married an engineer and lived in Hamburg. Since Hans Stosch Senior never left a will, Hedwig still had in theory a claim to the name Sarrasani; Mey obtained the right to use the name from her. With financial help from Albert Keller, a businessman from Munich, Fritz Mey created a new Circus Sarrasani from scratch. Mey’s knowledge of, and passion for, carpentry came handy for the building of a seating system and a fleet of circus wagons painted with the famous Sarrasani color scheme, green and white parted diagonally. He had a new big topThe circus tent. America: The main tent of a traveling circus, where the show is performed, as opposed to the other tops. (French, Russian: Chapiteau) made and a new façade designed—more modern in style than the original Sarrasani oriental façade but still monumental—which would become his circus’s trademark.Fritz Mey’s new Circus Sarrasani premiered in Mannheim on March 31, 1956, and went on to a national tour. The program gathered some remarkable names, such as the legendary Togare (who was past his prime, but still an iconic circus figure of a bygone era) with a group of lions; The Camilio Mayer high-wire troupe; McSovereign, the King of Diabolo; the famous Master Equestrian Jose Moeser; and the clown and ropedancer Walter Galetti.

Within a couple of years, Sarrasani positioned itself as one of Germany's major circuses, just behind the giants Krone and Franz Althoff. Nonetheless, Mey was soon caught in a legal trademark battle: From Argentina, Trude Stosch-Sarrasani (1913-2009), who was still the owner of the original Circus Sarrasani and had revived it in South America, started a lawsuit that would linger over three years, and which she eventually won. Undeterred, Mey then asked Trude to give him a temporary license to use the name, limited to Germany; this settlement request would lead to another conflict that would last for many more years, and taint the relationship between Fritz Mey and Trude.

In 1961 Fritz Mey bought a large winter quarters facility in Mörlenbach, in the Odenwald, southern Hesse, replete with a giant carpentry shop to allow him to build his own circus equipment. By the 1960s and through the 1970s, in spite of the rapid growth of medium-size quality circuses such as Williams, Busch-Roland, Willy Hagenbeck, Carl Althoff, and Barum-Kreiser, and the towering presence of the German giants, Krone and Franz Althoff, Sarrasani would remain one of Germany’s leading circuses—and a highly regarded one: In 1968, for his contribution to the revival of the German circus, Fritz Mey was awarded the Merit Cross 1st class of the Federal Republic of Germany.

In an environment dominated by circuses whose main asset was their vast menageries, Sarrasani remained a classic circus whose program was composed exclusively of hired acts. It was quite unusual in the business: Most of its competition were family-owned circuses whose programs relied on a base of family acts, or on animal acts from their own menageries. Mey’s rivals dubbed Circus Sarrasani "an agent's circus". Cage acts, elephants, horses and other animals were never missing however, but they were contracted for the season as any other acts.Many great names appeared in Sarrasani’s programs, such as the legendary juggler Francis Brunn in 1972. The circus regularly visited Austria, Holland, and Belgium, and even Switzerland—a country usually hard to penetrate for foreign circuses. In the spring of 1961 Sarrasani undertook an odd mini-tour around the "Portes" of Paris, which was a disappointment: In post-war France, the name Sarrasani was known only to a handful of circus aficionados and journalists; before the war, Hans Stosch’s circus had never wandered farther in France than Strasbourg, close to the German border. Furthermore, even sixteen years after the end of WWII, Parisian audiences were not hungry for German entertainment! That same year, 1961, Fritz Mey’s Circus Sarrasani also toured Germany and Austria under the title Amar, in association with the French circus of that name.

In the winter 1967-69 Circus Sarrasani visited Southern Italy, sponsored by the Italian impresario Egidio Palmiri—another disappointment in spite of a remarkable program featuring the high-wire duet Mendez & Seitz, Eugene Weidmann's group of mixed cats and bears, Rudi Lenz’s chimpanzees, the Schickler Sisters with their high schoolA display of equestrian dressage by a rider mounting a horse and leading it into classic moves and steps. (From the French: Haute école) riding act, the clown Walter Galetti on the bouncing ropeAn rope placed between two supports or pedestals, and fastened at one or both ends to a spring or bungee, so that the ropedancer can use the rope as a propelling device., and the clown trio Muñoz.

Meanwhile, the relationship between Fitz Mey and Trude Stosch-Sarrasani had finally improved, and Mey lured her back to Germany, offering her to present a liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip. act prepared for her in Italy by Enis Togni for the seasons 1976 and 1977. Yet, featuring a sixty-three-year-old former circus glory, even such a legendary one as Trude, was not really what Circus Sarrasani needed. For all its good intentions, Fritz Mey’s Circus Sarrasani was becoming passé. Mey didn’t have the creative mind and innovative genius of Hans or Trude Stosch-Sarrasani: His programs had become predictable. Furthermore, the circus’s equipment was heavy and outdated; everything was made of wood—even the stringers of the seating system and the gigantic façade. This cumbersome equipment still traveled entirely by rail, and the cost of moving the circus was consistently rising.

In 1980, plagued with mounting debts, Fritz Mey decided to stop his circus’s operation and cancelled its tour. Instead, he went on to manage a German tour of Enis Togni’s huge, spectacular, and ultra-modern American Circus—in fact an Italian concern originally created in Spain by Arturo Castilla. His German colleagues met with open hostility Mey’s association with this invading foreign circus. In the circus world, many announced the impending demise of Fritz Mey’s Circus Sarrasani.

Ingrid and André Sarrasani

Ingrid Wimmer, born in Hannover on June 28, 1933, arrived at Circus Sarrasani in 1958 as Coronet Cordon, a member of the cowboy act of Fred Cordon. In time, Fritz became romantically involved with the attractive Ingrid. After the death of Mey's wife, Ruth (née Bitterlich), Ingrid gave Fritz a son, André, born in Heidelberg on November 3, 1972. The difference of age between Ingrid and Fritz (she was thirty-nine, he was sixty-six) and their illicit union created a minor scandal in the circus community; nonetheless, Fritz, whose marriage to Ruth had been childless, was quite proud to have at last an heir apparent.

Ingrid showed a keen interest in, and ability for, circus management. She became Fritz’s right hand, and Trude Stosch-Sarrasani duly noted her strength and determination. In 1976, Trude legally adopted Ingrid; thus Trude, who didn’t have children, established a continuity of the Sarrasani lineage—even if it might have appeared a little twisted to many. Ingrid became officially known as Ingrid de Stosch-Sarrasani—with the bizarre addition of the French aristocratic prefix "de", which doesn’t belong to the name. In the fall of 1980, she took over the management of the circus, creating a new legal company and rebuilding the business as a more efficient and healthier enterprise.Ingrid adapted the circus to the 1980s, improving lighting, the rhythm of the show, and other production elements, yet remaining faithful to the same artistic formula—a simple continuity of good acts. The circus equipment was also modernized. For the 1985 season, she starred the celebrated award-winning trapeze artist and daredevil Elvin Bale, billed as a "Superman from USA". André succeeded his mother at the end of the decade. Under the guidance of the well-known circus magician-turned-talent-agent Lee Pee Ville, he established himself as a magician working with wild animals, in the style popularized by Las Vegas magicians Siegfried and Roy.

André tried to revamp the show around his act, with a rock-n-roll band and "disco" lighting. Through the 1990s, André expanded the formula with a series of hybrid but pleasant experiments, in which a contemporary, rock-n-roll style contrasted with Eastern-European standard animal acts and classic clown entrées. These were the years when classic European circuses were struggling to find a new identity, navigating erratically between the new standards successfully set by Circus Roncalli (a pure classic look inspired by old German circus imagery—notably Sarrasani’s) on one side, and the "new look" of Cirque du Soleil.

Epilogue

Fritz Mey, who could have opted for the first of those new circus styles but failed to evolve, passed away in Mörlenbach on December 1, 1993, at age eighty-seven. Circus Sarrasani became increasingly a showcase for André Sarrasani’s magic extravaganzas, with shows bearing such titles as Magic Vision (1995) or Sensations (2002). André eventually showed more talent for business than for maintaining his circus heritage. He abandoned the regular tours, favoring the production of special events and sedentary winter-circus shows in Wiesbaden or other cities, where he developed significant relationships with the city governments.

Ingrid Stosch-Sarrasani passed away at the age of eighty-eight on April 28, 2022, in Radebeul, the Stosch-Sarrasanis hometown near Dresden. But all was not lost: André Sarrasani reestablished a Sarrasani presence in Dresden in 2004, when he opened there the Sarrasani Trocadero, an elegant dinner-show given under a stationary tent structure with a façade reminiscent (in a much smaller version) of the legendary Circus Sarrasani of yore.

Suggested Reading

- Hans Stosch-Sarrasani, Jr., Durch die Welt im Zirkuszelt (Berlin, Volksverband der Bücherfreunde, Wegweiser-Verlag, 1940)

- Gustav van Hahnke, Zirkus Sarrasani — Hinter den Kulissen einer Weltschau (Berlin, Erich Schmidt Verlag, 1952)

- Ernst Günther, Sarrasani — wie er wirklich war (Berlin, Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, 1984) — 1991 revised edition: ISBN 3-362-00454-7

- Ernst Günther, Der lachende Sarrasani — Anekdoten aus der Welt eines berühmten Zirkus (Husum, Husum Druck, 1992) — ISBN 3-88043-613-9

- Gustavo Bernstein, Sarrasani, entre la fábula y la epopeya (Buenos Aires, Editorial Biblos, 2000) — ISBN 950-786-248-X.

- Ernst Günther, Zirkusstadt Dresden (Dresden, Tauchaer Verlag, 2002) — ISBN 3-89772-049-3

- Ernst Günther, Sarrasani: Geschichte (und Geschichten) (Dresden, Sächsische Zeitung, 2005) — ISBN 3-938325-15-1

See Also

- Video: Historia del Circo Sarrasani (in Spanish) (1999)