The Indian Circus

From Circopedia

By Dominique Jando

In recent years, the Indian circus has acquired a rather unsavory reputation abroad. Stories of children abducted or bought and forced into bondage, training in horrifying conditions and performing to enrich their "owner"—the circus proprietor—have surfaced in the Western press. Indeed, in a country where the level of extreme poverty is still fairly high, a few traveling circus entrepreneurs may have resorted to methods that have fortunately vanished more than a century ago in the western world.

A Marginal Industry

By and large, Indian circus entrepreneurs have also maintained the belief that there are "secrets of the trade" in the training of circus acrobats and circus animals, which has certainly contributed to the dubious reputation of an industry that is often seen as marginal, and not well adapted to the modern world. Today (2010), the traditional Indian circus suffers from a sharp decline in attendance, while foreign circus companies (mostly Russian) visiting the region, or traveling with Indian circuses, still attract a large public.

One of India’s principal circus producers, M. V. Shankaran, recently complained: "The biggest problem in our way is getting the artistes, who require constant and vigorous training from a very young age." (Indian Express, February 25, 2009.) This revealing comment denotes actually the true problem—that is, the way Indian circus producers have approached the recruitment of their artists, and the making of their acts. The staff of any circus of importance in India includes training coaches, and the acts they create constitute a somewhat permanent repertoire, and are, by tradition, the exclusive property of the circus.

Another comment that illustrates well the Indian approach to circus arts is that "Circus is widely seen as a dangerous profession. So most families, even those who find it difficult to make both ends meet, are unwilling to send their young ones to join it." (K. P. Hemraj, former director of the Amar Circus.) These comments explain perhaps why there are no true circus dynasties of performers in India: There, circus performing seems to be perceived as a refuge for society’s leftovers! In April 2011, however, the Indian Government passed a law forbidding circuses to employ children under 14 years of age, placing children performers under the same protection as in other industries.

Chatre's Great Indian Circus, The First Indian Circus

The circus tradition in India dates back to the late nineteenth century—although India has of course a much more ancient tradition of traveling entertainers, comparable and parallel to those of Asia and Europe, and who often cross-pollinated with them. But the first Indian circus, according to the definition of the art form created by Philip Astley in 1770, didn’t appear until 1880.

Its creator was Vishnupant Chatre, a riding master who doubled as a singing teacher. Chatre was born in the village of Ankakhop (now part of the city of Sangli), in the province of Maharashtra, southeast of Bombay (the present Mumbai). Chatre was in charge of the stables of the Rajah of Kurduwadi, where he occasionally performed "feats of horsemanship"—in the tradition of old English riding masters such as Philip Astley.

As legend has it, Chatre and the Rajah went to see a performance of the Royal Italian Circus of Giuseppe Chiarini in Bombay. The peripatetic Italian director (whose company was generally based in North America) was on one of its many world tours, and visited Bombay for the first time in 1774. Chiarini was a remarkable equestrian, and Chatre was duly impressed by his performance, and also by his show. During a conversation with Chatre and the Rajah, Chiarini bluntly stated that India was not ready to have a circus of its own, and that it would take at least ten years before it could happen; Chatre was piqued.

Thus Vishnupant Chatre decided to organize his own circus, of which he would be the star equestrian, and his wife would become a trapeze artist and an animal trainer. He probably used some of his pupils in the equestrian department as well. The first performance of Chatre’s Great Indian Circus was held on March 20, 1880 in the presence of a selected audience—among which was the Rajah of Kurduwadi, who may have helped him in starting his venture.

Following the model of Chiarini, Chatre’s Great Indian Circus went on to travel extensively, first in the vast regions of North India, then further south, to the large east-coast city of Madras (today’s Chennai), and down to the Island of Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka). In 1884, Chatre embarked in a tour of Southeast Asia, and, according to Indian circus lore, he then crossed the ocean to conquer the United States. But here, Chatre had badly overestimated his powers: He was indeed unable to measure up to the giant American circuses, neither in size nor in quality, and he returned to India in defeat. However, no record is known of Chatre's performing in the United States.

Keeleri Kunhikannan, The Father Of The Indian Circus

Back in India, Chatre continued his travels. When his circus visited the city of Thalassery (Tellicherry), on the Malabar Coast in the Indian state of Kerala (South West of India), he met Keeleri Kunhikannan (1858-1939), a martial arts teacher, who also taught gymnastics in Hermann Gundert’s Basel Evangelical Mission School. Chatre was aware that acrobats were slowly taking preeminence over equestrians in European and American circuses, and his show was a little deficient in that department.

Thus Chatre asked Kunhikannan, who showed a keen interest in the circus, to train acrobats for his Great Indian Circus—which Kunhikannan began to do in 1888 at a kalari (Indian martial-arts facility) in the village of Pulambil. In 1901, Kunhikannan opened a bona-fide circus school in Chirakkara, a village near the city of Kollam. In 1904, one of Kunhikannan’s students, Pariyali Kannan, created his own company, the Grand Malabar Circus, whose life lasted only two years.

But this was only the first of several circuses emanating from the Chirakkara’s circus school, and soon, Kerala would be known as the Cradle of the Indian Circus. Over the years, Chirakkara's school gave birth to such companies as the Whiteway Circus (created in 1922 by Kunhikannan’s nephew, K. N. Kunhikannan), the Great Rayman Circus (created in 1924 by another disciple of Kunhikannan, Kallan Gopalan), the Great Lion Circus (also founded by K. N. Kunhikannan), the Fairy Circus, the Eastern Circus, the Oriental Circus, the Gemini Circus, and the Great Bombay Circus.

To these, one must add the Kamala Three Ring Circus of K. Damodaran, who had begun his career traveling from village to village with a small two-pole tent in the early 1930s, before ending with a giant American-style six-pole, three-ring circus, the very first—and only one—of its kind in Asia.

The Chirakkara’s circus school didn’t train only future circus entrepreneurs: Many of Kunhikannan's pupils became circus stars in India, and sometimes internationally. The most famous of them is perhaps Kannan Bombayo, the legendary ropedancer, who graduated from Kunhikannan’s school in 1910, was a star performer in the United States in the 1930s, and was subsequently featured in several major European circuses.

After Kunhikannan’s death in 1939, one of his disciples, M. K. Raman created the Keeleri Kunhikannan Teacher Memorial Circus and Gymnastic Training Centre, still in Chirakkara, and the tradition established by Kunhikannan has continued to this day. (In 2008, the Indian government announced that a Circus Academy would be created in Thalassery in Kunhikannan’s memory.)

Another Era

At the turn of the twenty-first century, India had twenty three active circuses, grouped in a national federation. Yet, the image of the Indian circus, with its children performers taken in apprenticeship by circus companies and apparently more or less forced into training, its generally shoddy working environment, and the poor conditions in which its animals were often kept, eventually caught up with the general perception of the industry in India.

In 2013, the Indian government banned the use of wild animals in the circus, as well as child labor in performances. Economically, these were two staples of the Indian circuses that allowed them to considerably lower the costs of their productions. Without these elements, many entreprises were not able to operate anymore. Other regulations were put into motion, which several circus owners who only knew a traditional system gestion that had, in many aspects, not changed since the nineteenth century, became overwhelmed by the amount of bureaucracy they had to face, went bankrupt or simply gave up.

Today (2015), the Indian circus is struggling to adapt to a concept of circus vastly different from the model they had developed in the nineteenth century, and by failing to keep apace with the rest of world in the twentieth century, was eventually condemned to fall apart in the twenty-first.

Some of India’s Major Circuses

In spite of its recent situation, circus has flourished in India since the days of Vishnupant Chatre and Keeleri Kunhikannan. If the Indian circus tradition has perhaps become a little too isolated from the international circus scene, it has nonetheless long been a significant part of India’s popular entertainment culture. After the end of the British Raj and the independence of India in 1947, several new circuses have appeared on the scene, joining some of the ancient troupes that are still active today (2010).

• Great Royal Circus

One of the oldest circus troupes in India, the Great Royal Circus dates its origins to 1909, when it was known as Madhuskar's Circus; in the 1970’s, when it was taken over by N. R. Walawalker, it became the Great Royal Circus. Narayan Rao Walawalker, an animal trainer, made it one of the very few Indian Circuses that have toured internationally—traveling in Africa, the Middle East, and Southern Asia.

• Great Rayman Circus and Amar Circus

The Great Rayman Circus is one of the oldest circus companies in India, founded in 1920 by Kallan Gopalan, a disciple of Keeleri Kunhikannan, and one of the great Indian showmen of that period. In times, Kallan Gopalan built a circus empire that comprised, the National Circus and the Bharat Circus among others. The Amar Circus, which Gopalan created in the 1960s, is still active to this day, and was recently under the management of K. P. Hemraj.

• Great Bombay Circus

Baburao Kadam founded the Grand Bombay Circus in 1920. It toured initially in Sindh and Punjab, now provinces of Pakistan. K. M. Kunhikannan, Keeleri Kunhikannan’s nephew and a versatile artist who created the Whiteway and Great Lion circuses, merged his two companies with the Grand Bombay Circus in 1947—which was renamed Great Bombay Circus.

After K. M. Kunhikannan’s death in 1953, his nephew K. M. Balagopal succeeded him and became the main partner in the Great Bombay Circus. Under his management, the circus, with its 300 employees and a menagerie of more than 60 animals, has become one of the biggest circuses in India. It recently performed in Sri Lanka and South Africa.

• Gemini Circus

The Gemini Circus was created in 1951, in Billimoria, a town in the State of Gujarat (India’s westernmost region, south of Pakistan), by circus entrepreneur Moorkoth Vangakandy Shankaran (born June 13, 1924, and popularly known as Gemini Shankarettan), a native of Tellicherry, Kerala, and the son of a schoolteacher. After service in the Indian Army during WWII, Shankaran joined M. K. Raman’s circus school in Chirakkara, and became an aerialistAny acrobat working above the ring on an aerial equipment such as trapeze, Roman Rings, Spanish web, etc. and gymnast on horizontal bars.

Shankaran worked for a time with Kallan Gopalan’s Great Rayman Circus, and then created his own Gemini Circus, in association with another entrepreneur, K. Sahadevan. The circus opened its doors on August 15, 1951. In 1964, Shankaran led the first Indian circus delegation to an International Circus Festival held in the USSR. The Indian company performed in Moscow, Sochi, and Yalta. Shankaran, whose elder brother had been a famous communist activist in India, and who had himself communist inclinations (his wife, V. P. Shobhana, a lawyer, is also the niece of a famous Marxist leader) was of course a welcome guest.

Notwithstanding his Marxist affinities, Shankaran expanded his business empire, becoming a partner in other circus ventures: Apollo Circus, Vahini Circus, and the Jumbo Circus, which he started in 1977. He is also the CEO of the Palmgrove Heritage Retreat, a vacation resort in Kannur, Kerala. Shankaran has two sons, who are managing partners in his circus ventures, Ajay Shankar and Ashok Shankar, and a daughter.

The Gemini Circus has built ties with the Indian film industry, which has used it as a background for popular movies such as Raj Kapoor ‘s Mera Naam Joker, Mithun Chakraborty's Shikari, and Kamala Hassan's Apoorva Sahodarangal.

• Rajkamal Circus

A young daredevil, Gopalan Mulloli started his small circus company the village of Zeera, in Punjab, in 1958. His circus was named after his son, Raj, and his wife, Kamala, by combining their names into Rajkamal. The Rajkamal Circus steadily grew in importance and made extensive tours in India visiting its largest cities, and later in the countries of the Gulf. It is today one of the largest circuses of India.

• Jumbo Circus

M. V. Shankaran’s Jumbo Circus, "The Pride of India," opened its doors on October 2, 1977, in Dhanapur, in the state of Bihar (in Eastern India). It is probably the best known, and the largest circus in India—a modern enterprise that, since its inception, had included a important traveling menagerie. It is part of the conglomerate of circuses owned by the Shankaran family (see Gemini Circus, above); In recent years, it has presented a company of Russian performers.

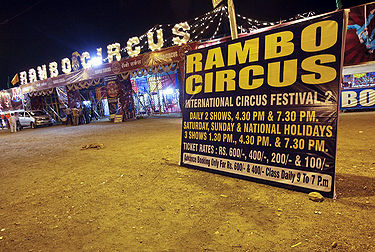

• Rambo Circus

Rambo Circus was created by P.T.Dilip in 1991, out of the fusion of four old Indian circuses: Oriental Circus, Arena Circus, Victoria Circus, and Fantasy Circus. Rambo Circus has toured India extensively and also the Middle East. It is run today (2011) by Sujit and Sumit Dilip, the sons of its founder.

Suggested Reading

- Mary Ellen Mark, The Indian Circus (San Francisco, Chronicle Books, 1993) — ISBN 0-8118-0531-X

- Sreedharan Champad, An Album of Indian Big Tops (History of Indian Circus) (Houston, Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co., 2013) — ISBN 978-1-62212-766-5