Kannan Bombayo

From Circopedia

Acrobat, Rope Dancer

By Dominique Jando

Between the two World Wars, in Europe and in America, the diminutive Indian acrobat Kannan Bombayo (1907-1939) was considered the world’s greatest acrobat on the bouncing ropeAn rope placed between two supports or pedestals, and fastened at one or both ends to a spring or bungee, so that the ropedancer can use the rope as a propelling device.—which indeed he was. His career, unfortunately, was meteoric: he was only thirty-two when he died on his return voyage to India. Still, his name holds a major place in Indian circus lore and legend, and in circus history in general: Not only was Kannan Bombayo incontestably the best in his specialty—he also introduced it to the West.

N.P. Kunchikannan

Kannan Bombayo was born May 30, 1907 in Chirakkara, a borough of Tellicherry (today Thalassery), on the Malabar Coast, in the Indian state of Kerala. His father, Eerayi Korumban, struggled as a small farmer, and was not connected with the circus. In India, children’s names are different from their father’s; Kannan Bombayo’s birth name was N. P. Kunchikannan—the Indian contracted spelling of Kunchi Kannan: He became familiarly known as Kunchy.

Kunchy’s place of birth had a definite impact on his life: Chirakkara was home to Keeleri Kunhikannan’s first Indian circus school. Considered the "Father of the Indian Circus", Keeleri Kunhikannan trained the first crop of India’s professional circus artists, several of whom went on to create their own shows, and the State of Kerala became known as "The Cradle of the Indian Circus." Furthermore, Keeleri was Kunchy’s uncle…Keeleri enrolled Kunchy in his school when the young boy was just seven years old. There he was trained in acrobatics, perch-poleLong perch held vertically on a performer's shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. balancing and other circus skills; he was a remarkable tumbler who could turn a roundoff-double back somersault on the ground. He later specialized in acrobatics on the bouncing ropeAn rope placed between two supports or pedestals, and fastened at one or both ends to a spring or bungee, so that the ropedancer can use the rope as a propelling device., an act popularized in India by Keeleri’s brother-in-law, O. K. Chandu (known as Charlie), who was in all probability Kunchy’s original teacher in that discipline. (Kunchy later christened his son, Charlie.)

Although bounding rope acts are popular (but not very common) today, it was not the case back then. Chandu, and, like him, Kunchy, bounced on a rope made of coconut strands and stretched between two bamboo X-frames. The rope had a great elasticity but needed to be tightened back with a pulley attached at one end after each series of jumps; it was neither practical nor very safe. Nonetheless, Kunchy, who was short (about 1.50 meters, or 5 feet tall)—always a plus for an acrobat—quickly showed an uncanny ability on his coconut rope; soon he was turning front and back somersaults, twisted somersaults, and finally, a double back somersault, taking off and landing astride the rope.

When later Kunchy began to work in Europe, his rope was rigged very high, at about 3.50 meters (13 feet) off the ground, which not only rendered his tricks rather dangerous, but also made his act quite spectacular—even more so because of his small stature. There are no pictures of young Kunchy performing in India, so it is hard to say if he already worked high then, but considering the very nature of the ropes he used, it is quite likely.

Kunchy made his debut in the ring at age ten, in 1917, in the acrobatic troupe of Chirammal Karunthandi Ambu, at the Sheshappa Circus of Sandow Sheshappa. He started performing his bouncing ropeAn rope placed between two supports or pedestals, and fastened at one or both ends to a spring or bungee, so that the ropedancer can use the rope as a propelling device. act in 1922 (at age fifteen) in the newly created Whiteway Circus of his uncle’s son, Keeleri Kunhikannan, Jr., in Thrissur, the "cultural capital" of Kerala. Kunchy remained for several years with the Whiteway Circus, where he was given, in time, some managerial responsibilities on top of his work as a performer.

The Whiteway Circus had a very good reputation, and was sometimes compared to an European circus—a true label of quality in India, where Giuseppe Chiarini’s visit in the 1880s had not been forgotten: Circus Chiarini was still the standard against which all Indian circuses were measured. Keeleri Kunhikannan, Jr. often hired foreign artists for his show; one of them would have a decisive influence on Kunchy’s career: Ottavio Canestrelli (1897-1977), head of the Canestrelli Family’s free ladderUnsupported vertical ladder on which acrobats perform balancing and/or juggling tricks. act.

The Canestrellis

The Canestrellis were (and still are) an old and numerous Italian circus family, whose origins date back to the mid-nineteenth century in Padua; they created their own circus in 1903. Ottavio was third-generation Canestrelli, the son of Riccardo (c.1878-1958) and Teresa, née Fumagalli. He was an extremely versatile performer: Originally trained as an acrobat and a bareback rider, he was also an excellent juggler and equilibrist. He had married a Neapolitan opera singer, Genoveffa Lentini (1902-1995), known as Giovanna. With her, their children Riccardo and Tosca, and his brother Federico, Ottavio had been engaged since 1928 in a series of circus tours in South-East Asia, the Middle East and India. The family’s main specialty then was a free ladderUnsupported vertical ladder on which acrobats perform balancing and/or juggling tricks. act, but they could perform a variety of acts, notably Ottavio's juggling and bareback riding.

At the turn of 1931, the Canestrellis were ready to sail back to Europe for a contract with the giant Cirkus Kludsky in Czechoslovakia. Since they had six weeks to wait before their sea passage, Ottavio accepted a short engagement with Kunhikannan’s Whiteway Circus, where he met Kunchi Kannan.Ottavio was duly impressed by the Indian acrobat's skills—albeit less so by his costume, which consisted of white tights and a red trunk, or his showmanship (often lacking with Indian and Asian performers). Kunchy’s apparatus also seemed a little precarious... Nonetheless, Federico Canestrelli and Kunchy, who were about the same age, became fast friends, and Federico convinced Ottavio (with some help from Keeleri Kunhikannan) to take Kunchy, who wanted to see the world, in the family troupe.

The Canestrellis debuted at Cirkus Kludsky in 1931 with three acts: Ottavio’s juggling act; a clown trio composed of Giovanna, Ottavio and Federico; and the family’s free ladderUnsupported vertical ladder on which acrobats perform balancing and/or juggling tricks. act, which included an amazing three-man-high column on an unsupported ladder. Meanwhile, Ottavio began concocting an "Indian production" that would include Kunchy and his bouncing ropeAn rope placed between two supports or pedestals, and fastened at one or both ends to a spring or bungee, so that the ropedancer can use the rope as a propelling device. act. In order to do so, however, he had to build for him a new and more practicable apparatus that could work in a European circus.

He came up with a manila rope stretched between two metallic A-frames, and rigged with bungees at each end—a new and original system then, which replaced Kunchy’s rudimentary coconut and bamboo contraption. It took time for Kunchy to get used to it, but it worked. Ottavio also gave Kunchy much needed performing lessons... and a new costume. After several months of practice, the new act was ready, and it was introduced in the Kludsky show, where Kunchy performed for the last two months of the season. He was an overnight sensation.

His act was also ready just in time for the auspicious visit of one of John Ringling’s talent scouts: The family was immediately offered a contract to perform in the United States with Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus the following season. It was a bonanza that owed mostly to the Canestrelli’s "Indian production" and its main feature, The Mystery Man from India (as Kunchy was anonymously announced in early press releases). They would be part of the first tour of The Greatest Show On Earth under the management of Sam Gumpertz, who was taking over the circus from the ailing and cash-strapped John Ringling.

From Kunchy to Kannan Bombayo

Before going to the United States, the Canestrellis returned to Italy, and made a detour to Naples to fetch Giovanna’s sister, Filomena, whom they quickly train as the sixth member of the free ladderUnsupported vertical ladder on which acrobats perform balancing and/or juggling tricks. act. With Kunchy in tow, the family, which now also included Ottavio’s brother Gino, left Naples in March on the SS Conte Grande en route to New York. After a twelve-day crossing, they arrived in Manhattan in time for the Ringling opening at Madison Square Garden, scheduled on April 13, 1932.

One of the Ringling Circus’s immediate concerns was to give Kunchy a stage name; indeed, The Mystery Man from India was fun but it was a little too… mysterious. Neither Kunchy Kannan, nor N. P. Kunchikannan, sounded very good; Pat Valdo, Ringling’s performance director, and Ottavio eventually settled on Kannan Bombayo, which sounded "Indian" enough to an American ear, and was easy to pronounce. Most likely, Dexter Fellows, Ringling’s legendary Press Agent, had a major input in this choice. During rehearsals, Kunchy’s exceptional prowess impressed everybody—and notably the journalists invited by Fellows: He garnered a lot of publicity even before the show opened.Kannan Bombayo was one of the featured highlights of the new show, which also included The Codonas, Dorothy Herbert, the original Wallendas, and Hugo Zacchini—not too bad a company for an American debut! Kannan Bombayo was featured in the center ring and given a spectacular entrance, a true production number in which the Canestrelli family participated, including Ottavio who opened the proceedings parading a giant python named Satana (which he had acquired in Singapore at the beginning of his South-East Asian tour), before Kunchy’s own entrance mounted on an elephant, with another python looped around Kunchy's shoulders.

It was a beautiful image, but two days into the Garden’s season Satana rebelled and tried to curl around (and crush) Ottavio, who owed to a bevy of gutsy ring crews led by Alfredo Codona to be freed from the emprise of the powerful and deadly reptile. Both Codona and Canestrelli ended with serious snakebites, and Kunchy had a little less exotic introduction that night. Sadly, Satana, who had been injured in the melee, died a few weeks later, to Ottavio’s immense chagrin.

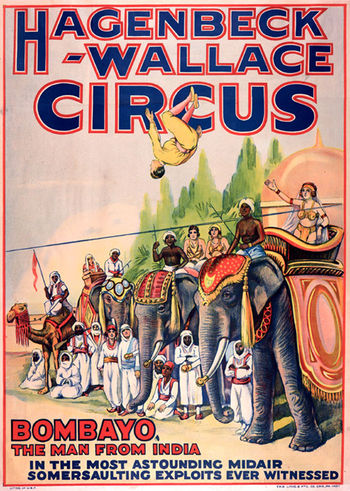

Meanwhile, Kunchy and Filomena Lentini had fallen in love. They were married during the tour at the Church of the Little Flower on Zarzamora Street in San Antonio, Texas, on September 19, 1932 (Alfredo Codona had married Vera Bruce the day before, on September 18). For the 1933 season, part of the Ringling cast was transferred to the Ringling-owned Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, including the Canestrellis and Kannan Bombayo, who was given major star treatment, including his own poster. Staged with even more glitz and grandeur, his ring entrance was now adorned with a parade of showgirls in oriental costumes.

The noises of Bombayo’s American success had reached Europe’s major circus directors—among which Bertram Mills, who signed Kunchy for his circus’s 1933-34 Holiday Season at London’s Olympia. Mills was one of Europe’s most prestigious circuses, and certainly the most elegant. On opening night, Kannan Bombayo performed in front of Prince George, the Duke of Kent, who represented the Royal Family. Bombayo not only received a royal accolade, but the English audiences also recognized in him an artist of exception, and gave his act a triumphal welcome. Cyril Mills signed Kunchy immediately for the 1935 Bertram Mills Circus’s touring season.

Triumphs And Tragedy

Kannan Bombayo then returned to the United States, where he had to complete his last touring season with Hagenbeck-Wallace. The Canestrellis had been sent to another Ringling-owned show, the Al G. Barnes Circus, and Kunchy was now on his own, with Filomena in Indian sari as his assistant. His friend Lalo Codona had replaced Ottavio as his spotter. According to Ottavio Canestrelli, Kunchy often had a short moment of hesitancy just before throwing his double somersault—a very bad habit, known in French circus lingo as a rat (from the French "raté"—a miss), which can mess up the trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.’s tempo and have very bad consequences.And thus he once missed his double somersault, and Lalo, taken by surprise, was unable to catch him or break his fall. Kunchy fell on his back, and suffered a lung contusion that was not immediately diagnosed. Considering Bombayo’s rather brutal daily exercises, it didn’t heal properly, and made him prone to pulmonary infections. He eventually contracted tuberculosis, a deadly disease that had no cure at the time. Filomena hid it from him, but it would in time put an end to his career, and kill him.

After a last appearance in the United States in February 1935 with the Al Sirat Grotto Circus in Cleveland, Ohio (a Shrine circus), Kunchy and Filomena returned to England for the 1935 season with the Bertram Mills Circus tenting show. As in the United States, Bombayo was duly heralded with his own poster. That same year, Filomena gave birth to their son, Charlie. Mills's touring contracts were signed for two years (Mills covered the United Kingdom in two seasons), but Kunchy would do a third season, and finished his long association with Mills at the end of the 1937 tour.

In November 1935, Kannan Bombayo had been featured at Paris’s legendary Cirque Medrano, where he was a huge hit with Medrano’s circus-savvy audience. He returned to the Parisian circus as a headliner in December 1936, after a stint at Berlin’s WinterGarten in November. At Medrano, he was reunited with his old friend Lalo Codona. (Lalo now worked with the triple-somersaulter Clayton Behee, who had replaced Alfredo after his accident in 1933.) In the magazine Cœmedia, the famous French circus chronicler Serge admiringly dubbed Bombayo "le félin du câble" ("the feline of the wire").

When Serge saw again Kannan Bombayo, probably at Bertram Mills Circus in 1937, Kunchy’s health was visibly deteriorating; in his book Histoire du Cirque (Paris, Librairie Gründ, 1947), Serge said he saw in him a man who knew he was dying. It may have been hindsight, but Kunchy was very ill indeed. He spent 1938 playing dates in variety theaters in Scandinavia and Germany, including Berlin’s WinterGarten, where he had the dubious honor to perform for Adolph Hitler.

The Last Curtain

Kannan Bombayo was still a major star on the circus and variety circuit, but it was increasingly difficult for him to work. He had an upcoming engagement with Circus Busch, but he finally cancelled it, and he and Filomena went to Naples to recuperate in the Lentini family home. Yet, sadly, there was actually nothing to be done. Filomena, who was well aware of Kunchy’s terminal condition (she never let him know the full extent of his illness) decided that Kannan Bombayo should die in his country of birth; in February 1939, Kunchy, Filomena and four-year-old Charlie set sail for India—where Kunchy had dreamt of establishing his own circus.Kannan Bombayo died at sea, on February 19, while the ship was off Athens. Filomena didn’t want Kunchy to be buried at sea, and it was arranged for his body to be kept in ice until their arrival in India two days later. She didn’t know there was a large welcoming committee waiting for them in Bombay: Kannan Bombayo, the little Indian acrobat who had become a circus star in Europe and America, was a living legend amidst the Indian circus community. A crowd of circus artists, circus students and their teachers, family members, and many people from Tellichery led by Keeleri Kunhikannan were on the dock to celebrate their hero’s return.

It was indeed a bitter blow when a tearful Filomena informed Kunhikannan that Kunchy was dead. Instead of a joyous celebration, a silent crowd escorted Kannan Bombayo’s body to the Shabari Crematorium in Bombay, where he was cremated according to Hindu custom. His ashes were then buried according to Christian ritual (Kunchy had converted to Catholicism when he married Filomena) in Bombay—possibly at the Sewri Christian Cenetery, although this is not known. Filomena and Charlie spent a couple of weeks with Keeleri Kunhikannan, and returned to Italy. She then went to England, where she remarried. Kunchy's son, Charlie, died at a young age (the date is not confirmed). Those who knew Filomena later thought she was a little odd. She had another child to whom she gave her former married name, Kannan.

Kannan Bombayo had not only become a legend in India, where he is still revered today by the circus community, but he also became a legend in the West. Although he shone in circus rings and on variety stages for only seven years, he is still remembered today as one of the greatest circus artists of the twentieth century, and although his skills on the bouncing ropeAn rope placed between two supports or pedestals, and fastened at one or both ends to a spring or bungee, so that the ropedancer can use the rope as a propelling device. may have been equaled today, they have not yet been surpassed.

Suggested Reading

Ottavio Canestrelli & Ottavio Gesmundo, The Grand Gypsy (Lulu Publishing Services, 2016) — ISBN 978-1-4834-4894-7