SHORT HISTORY OF THE CIRCUS

From Circopedia

By Dominique Jando

If the history of theater, ballet, opera, vaudeville, movies, and television is generally well documented, serious studies of circus history are sparse, and known only to a few circus enthusiasts and scholars. What little the public at large knows, on the other hand, is circus history as told over the years by imaginative circus press agents, and repeated—and often misunderstood and distorted—by writers of popular fiction, Hollywood screenwriters, and journalists too busy to investigate further. One of the most popular misapprehensions about circus history is the oft-repeated idea that circus dates back to the Roman antiquity. But the Roman circus was in actuality the precursor of the modern racetrack; the only common denominator between Roman and modern circuses is the word itself, circus, which means in Latin as in English, "circle".

Contents

- 1 Philip Astley: The Father Of The Modern Circus

- 2 The Circus Is Born

- 3 The American Traveling Circus

- 4 Circus Conquers the World

- 5 Evolution of the Circus Performance

- 6 The End of the Equestrian Circus

- 7 Changes at the End of the 2oth Century

- 8 Circus in the 21st Century

- 9 Suggested Reading

- 10 Image Gallery

Philip Astley: The Father Of The Modern Circus

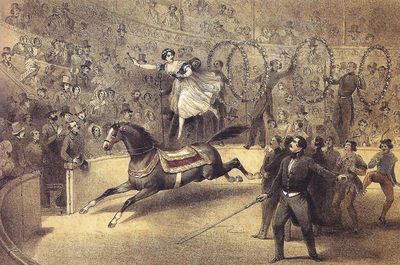

The modern circus was actually created in England by Philip Astley (1742-1814), a former cavalry Sergeant-Major turned showman. The son of a cabinet-maker and veneer-cutter, Astley had served in the Seven Years' War (1756-63) as part of Colonel Elliott's 15th Light Dragons regiment, where he displayed a remarkable talent as a horse-breaker and trainer. Upon his discharge, Astley chose to imitate the trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-riders who performed, with increasing success, all over Europe. Jacob Bates, an English equestrian based in the German States, who performed as far away as Russia (1764-65) and America (1772-73), was the first of these showmen to make a mark. Bates's emulators—Price, Johnson, Balp, Coningham, Faulkes, and "Old" Sampson—had become fixtures of London's pleasure gardens and provided Philip Astley with his inspiration.In 1768, Astley settled in London and opened a riding-school near Westminster Bridge, where he taught in the morning and performed his "feats of horsemanship" in the afternoon. In London at this time, modern commercial theater (a word that encompassed all sorts of performing arts) was in the process of developing. Astley's building featured a circular arena that he called the circle, or circus, and which would later be known as the ring.

The circus ring, however, was not Astley's invention; it was devised earlier by other performing trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-riders. In addition to allowing audiences to keep sight of the riders during their performances (something that was next to impossible if the riders were forced to gallop in a straight line), riding in circles in a ring also made it possible, through the generation of centrifugal force, for riders to keep their balance while standing on the back of galloping horses. Astley's original ring was about sixty-two feet in diameter. Its size was eventually settled at a diameter of forty-two feet, which has since become the international standard for all circus rings.

The Circus Is Born

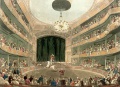

By 1770, Astley's considerable success as a performer had outshone his reputation as a teacher. After two seasons in London, he needed to bring some novelty to his performances. Consequently, he hired acrobats, rope-dancers, and jugglers, interspersing their acts between his equestrian displays. Another addition to the show was a character borrowed from the Elizabethan theater, the clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., who filled the pauses between acts with burlesques of juggling, tumbling, rope-dancing, and even trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-riding. With that, the modern circus—a combination of equestrian displays and feats of strength and agility—was born.Astley opened Paris's first circus, the Amphithéâtre Anglois, in 1782. That same year, his first competitor arose: equestrian Charles Hughes (1747-97), a former member of Astley's company. In association with Charles Dibdin, a prolific songwriter and author of pantomimes, Hughes opened a rival amphitheater and riding-school in London, the Royal Circus and Equestrian Philharmonic Academy. The first element of this rather grandiose title was to be adopted as a generic name for the new form of entertainment, the circus. In 1793, Hughes went to perform to the court of Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg, Russia; that same year, one of his pupils, British equestrian John Bill Ricketts (1769-1802), opened the first circus in the United States, in Philadelphia. In 1797, Ricketts also established the first Canadian circus, in Montréal. His only competition in America, the British equestrian Philip Lailson (who came to the U.S. in 1795), brought the circus to Mexico in 1802.

Circus performances were originally given in circus buildings. Although at first these were often temporary wooden structures, every major European city soon boasted at least one permanent circus, whose architecture could compete with the most flamboyant theaters. Similar buildings were also erected in the New World's largest cities: New York, Philadelphia, Montréal, Mexico City, et al. Although buildings would remain the choice setting for circus performances in Europe well into the twentieth century, the circus was to adopt a different format in the United States.

The American Traveling Circus

In the early nineteenth century, the United States was a new, developing country with few cities large enough to sustain long-term resident circuses. Furthermore, settlers were steadily pushing the American frontier westward, establishing new communities in a process of inexorable expansion. To reach their public, showmen had little choice but to travel light and fast.

In 1825, Joshuah Purdy Brown (1802?-1834) became the first circus entrepreneur to replace the usual wooden construction(French) A temporary circus building, originally made of wood and canvas, and later, of steel elements supporting a canvas top and wooden wall. Also known as a "semi-construction." with a full canvas tent, a system that had become commonplace by the mid-1830s. J. Purdy Brown came from the region of Somers, New York, where a cattle dealer named Hachaliah Bailey (1775-1845) had purchased a young African elephant, which he exhibited around the country with great success. Soon the addition of other exotic animals led to the creation of a bona fide traveling menagerie. Bailey's increasing prosperity convinced other farmers from the Somers area to go into the traveling-menagerie business—to which some added circus performances. In 1835, a group of 135 enterprising farmers and menagerie-owners, most of them from the vicinity of Somers, joined forces in creating the Zoological Institute, a trust that controlled thirteen menageries and three affiliated circuses, thus cornering the country's traveling-circus and menagerie business.With that, the unique character of the American circus emerged: It was a traveling tent-show coupled with a menagerie and run by businessmen, a very different model from that of European circuses, which for the most part remained under the control of performing families.

In 1871, former museum promoter and impresario Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810-1891), in association with circus entrepreneur William Cameron Coup (1837-95), launched the P.T. Barnum's Museum, Menagerie & Circus, a traveling show whose "museum" part was an exhibition of animal and human oddities soon to become an integral part of the American circus, the Sideshow.

In 1872, Coup devised a system of daily transportation by rail for their circus. Another of Coup's innovations of that year was the addition of a second ring. The circus had become by far the most popular form of entertainment in America, and Barnum and Coup's enterprise was America's leading circus. Ever the businessman, Coup resolved to increase the capacity of their tent. Due to structural limitations, this could only be done effectively by increasing the tent's length, which resulted in hampering the view for large sections of the audience. The addition of a second ring, then a third (1881) and, later, up to seven rings and stages solved the problem physically, if not artistically. It could be argued that it changed the focus of the show to emphasize spectacle over artistry. For better or worse, multiple rings and stages became another unique feature of the American circus.

Circus Conquers the World

The circus is essentially a visual performing art and therefore unfettered by language barriers. As a result, it is easily exportable to countries with native languages different from the language(s) of the performers. Early circus companies, realizing this, embarked on extensive international tours.In 1836, the British equestrian Thomas Cooke visited the United States and brought back to England the American traveling-circus tent. This innovation was to ease the task of a group of European circus pioneers consumed by global ambitions. The most remarkable of these early touring companies was managed by the Italian equestrian Giuseppe Chiarini (1823-1897). In 1853, Chiarini left Europe for America, where he created his own circus and went to the unchartered territory (as far as circus was concerned) of Havana, then went to South America, crossed the Pacific, and landed in Japan in 1855. In 1864, he settled in Mexico and toured Chile and Argentina before returning to Europe in 1869. In 1874, he went to China and then sailed to Brazil. In 1878, the company embarked on a tour of Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, Singapore, Java, Siam, India, and South America. And so it went, until the death of the intrepid Italian in Guatemala in 1897.

The French equestrian Louis Soullier (1813-1888), who managed Vienna's Circus at the Prater, toured the Balkans, settled for a time in Turkey, and then continued to China, where he introduced the circus in 1854. When he returned to Europe in 1866, he brought with him Chinese acrobats who in turn introduced traditional Chinese acts such as perch-poleLong perch held vertically on a performer's shoulder or forehead, on the top of which an acrobat executes various balancing figures. balancing, diabolo-juggling, plate-spinning, hoop-diving, et al., to Western audiences.

Another French equestrian, Jacques Tourniaire (1772-1829), went to Russia in 1816, where he established the first Russian circus. After his death, his sons Benoit and François followed in his footsteps, touring extensively in Siberia and traveling to India, China, and America.

On account of such extensive traveling, the circus was a global phenomenon long before the concept became commonplace. As a result of their international character, traditional circus dynasties experienced some confusion concerning national identities. The German equestrian Carl Magnus Hinné (1819-1890) established circuses in Frankfurt, Warsaw, Copenhagen, and in 1868, St. Petersburg and Moscow, where he was later succeeded by his Italian brother-in-law, Gaetano Ciniselli (1815-1881). Thus German and Italian names like Hinné and Ciniselli became associated with Russia. The French Gautier family is known as a Scandinavian circus dynasty. Some of the German Schumanns became a household name in Denmark, although the "Danish" Schumanns are Swedish. The first "French" circus dynasty was founded by an Italian, Antonio Franconi. And so on...European circus companies had ventured so far from home because they hoped to increase their profits. Their success in doing so was not lost on the handful of American circus entrepreneurs who would follow their lead.

Before entering into a partnership with P.T. Barnum in 1881, James Anthony Bailey (1847-1906) had embarked his Cooper & Bailey Circus on a trip to Honolulu, the Fiji Islands, Tasmania, the Dutch East Indies, Australia, New Zealand, and South America, a journey that lasted from 1876-78. After Barnum's death, Bailey took their Barnum & Bailey "Greatest Show on Earth" on an extensive European tour, from 1897 to 1902, which introduced bewildered Europeans to P.T. Barnum's gargantuan vision of the circus as a touring show that traveled nightly by special trains and, every day, set up and tore down immense canvas tents that housed an amalgam of triplicate circus, zoological exhibition, and freak-show.

If the three-ring format and the sideshow met with only middling enthusiasm, European circus owners were nonetheless impressed by Barnum & Bailey's touring techniques, and menagerie owners, whose business was fading at the time, were quick to recognize the advantages of adding a traveling circus to their zoological exhibitions. Thus, the tented circus and menagerie developed in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century.

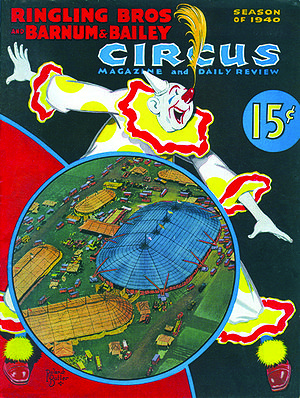

When Bailey returned to the U.S. in 1902, he found his old market under the control of serious competition: the giant circus conglomerate created by the Ringling Brothers, Al (1832-1916), Otto (1837-1911), Alf T. (1863-1919), Charles (1864-1926), and John (1866-1936). One year after Bailey's death in 1906, the Ringlings acquired Barnum & Bailey, which they combined with their own circus in 1919 under the title Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows.

In Europe, the traveling circus and menagerie reached its peak between the two World Wars, especially in Germany, where the flamboyant traveling enterprises of Krone, Sarrasani and Hagenbeck dominated the market. In large cities, however, circus performances were still given in circus buildings; Sarrasani had its own building in Dresden, Krone in Münich, Hagenbeck in Stellingen, and Paris alone maintained four permanent circuses. This, of course, created a demanding audience (in large cities, at least) who had grown accustomed to a degree of comfort and a fairly high level of production values in their elegant circus buildings. While in the U.S. the tenting techniques developed by W.C. Coup would remain practically unchanged for over a century, German and Italian tent-makers—and later French—constantly developed new systems for circus tents and seating, which eventually made some European traveling circuses nearly as comfortable and production-efficient as any permanent building.

Evolution of the Circus Performance

Changes weren't restricted to the commercial and physical aspects of the circus. The performance had evolved considerably since Astley and, at the turn of the twentieth century, was undergoing fundamental changes.From its inception, the core of the circus performance had been equestrian acts (trickAny specific exercise in a circus act.-riding, bareback acrobatics, dressage or High School, presentation of horses "at liberty"Liberty act", "Horses at liberty": Unmounted horses presented from the center of the ring by an equestrian directing his charges with his voice, body movements, and signals from a ''chambrière'' (French), or long whip.," and even comedy on horseback) interspersed with acrobatic, balancing, and juggling acts. Dibdin and Hughes had added to that original fare the pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances)., a dramatic presentation which traditionally ended the performance and involved a good amount of tumbling, clowning (not necessarily mute), and equestrian displays. Pantomimes often reenacted famous battles which, true to Astley's spirit, gave equestrian performers a good opportunity to demonstrate "the different cuts and guards as in real action" or "a general engagement, sword in hand, with the different postures of offence, for the safety of man and horse..." [From an old Astley's handbill] Pantomimes remained extremely successful during the nineteenth century and survived under various forms well into the twentieth. The last notable circus pantomimeA circus play, not necessarily mute, with a dramatic story-line (a regular feature in 18th and 19th century circus performances). was a spectacular adaptation of Lewis Wallace's Ben Hur which the French circus Gruss performed for several years in the 1960s.

Although in the middle of the nineteenth century equestrians, male and female, were still the true stars of the circus, acrobats began getting more and more attention. Not surprisingly, it started with acrobats on horseback, especially Americans such as John H. Glenroy, who accomplished the first somersault on horseback in 1846. "Floor" acrobats were also quick to make their mark. The best of them were often clowns. At first, circus clowns were essentially skilled parodists who might talk, sing, ride a horse, juggle, present trained animals, do balancing acts, or tumble. In the first half of the nineteenth century, an English clownGeneric term for all clowns and augustes. '''Specific:''' In Europe, the elegant, whiteface character who plays the role of the straight man to the Auguste in a clown team., Little Wheal, became famous for regularly performing a hundred consecutive somersaults in tempo—quite a feat, then or now.

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, tight-rope dancers were the fairgrounds' undisputed stars and were among the first acrobats to appear in the circus ring. There, they developed an adaptation of their art which would eventually become one of the circus's most prized attractions: the trapeze. They began by swinging on and hanging from a slack rope. Eventually, a bar was added in the middle of the ropes while the half ropes on each side moved toward a vertical position. With that, the trapeze was born. In 1859, a French gymnast, Jules Léotard (1838-70), presented at Paris's Cirque Napoléon (today Cirque d'Hiver) an act titled La Course aux Trapèzes, in which he jumped from one trapeze to another. Léotard had invented the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze), for which he became the toast of Europe—as much for his act as for the revealing costume he originated and which is still used today by acrobats and dancers, the leotard.By the close of the nineteenth century, railways and automobiles had begun to replace horses. Although major European circuses were still operated by equestrian families, equestrian displays were losing their supremacy to trainers of exotic animals (especially big cats), acrobats, aerialists, jugglers, and clowns. While some trained exotic animals had appeared early in circus history—around 1812 at Paris's Cirque Olympique, the Franconis presented Kioumi, the first trained elephant—it was the European combination of circus and menagerie that triggered the vogue of wild-animal presentations, which were developed in large part in Germany by the Hagenbecks, the world's foremost importers and dealers of exotic animals. Another significant transformation factor was a renewed interest in gymnastics and physical activities (which led to the resurrection of the Olympic Games in 1896) at a time when few gymnasts could be seen outside the circus.

The End of the Equestrian Circus

After World War I, the traditional equestrian circus was just a memory. Its legendary stars—Andrew Ducrow, Laurent Franconi, François Baucher, Ernst Renz, Oscar Carré, Albert Schumann, among others—had been replaced by the likes of triple-somersaulter Alfredo Codona on the flying trapezeAerial act in which an acrobat is propelled from a trapeze to a catcher, or to another trapeze. (See also: Short-distance Flying Trapeze), Con Colleano dancing on the tight wireA tight, light metallic cable, placed between two platforms not very far from the ground, on which a wire dancer perform dance steps, and acrobatic exercises such as somersaults. (Also: Low Wire), juggling legend Enrico Rastelli, and star-clowns such as François, Paolo & Albert Fratellini, Grock, and Charlie Rivel. (Clowns in Europe had remained true to their theatrical roots and maintained an important role in the circus. In America, however, victims of both the size of the tents and the three-ring format, they became speechless characters confined to oversized visual gags.)The most consequential early-twentieth-century innovation in the circus, however, occurred in Russia. In 1919, Lenin nationalized the Russian circuses, and the vast majority of their performers, natives of Western Europe, fled the country. Faced with the task of training a core of uniquely Russian performers, the Soviet government established, in 1927, the State College for Circus and Variety Arts, better known as the Moscow Circus School. Not only did the school rejuvenate the Russian circus, it also developed training methods modeled after sport-gymnastics, created original presentations with the help of directors and choreographers, and even originated innovative techniques and apparatuses that led to the invention of entirely new kinds of acts.

When, in the late 1950s, the Moscow Circus (a generic name adopted by all Soviet circus companies touring abroad) started showing in the West, those trained by the Soviet school contrasted favorably with those trained by the traditional circus families. Russian performers displayed originality, unparalleled artistry, and amazing technique, whereas the rest just repeated themselves in a desperate attempt to compete with both the Russian innovations and increasing competition from movies, radio, and television, which they did using the only weapons at their disposal: time-tested traditional acts. But resistance to change had transformed tradition into routine. The old circus families were losing touch with their audience's ever-transforming world.

Changes at the End of the 2oth Century

Old circus performers may have resisted change, but a few producers, at least, tried to shake up the shows in which they appeared by modernizing staging, lighting, musical accompaniment, and more: John Ringling North in the U.S.; Bertram Mills and his sons, Cyril and Bernard, in England; and Jérôme Medrano in Paris. Eventually, the new Russian style prevailed. In 1974, Annie Fratellini (heiress to the famous clowning dynasty) and Alexis Gruss, Jr. (heir to the last French equestrian dynasty) created in Paris the first two western circus schools. Both incorporated a performing arm—a circus in which creation was paramount—though both schools retained a more or less traditional approach. (Alexis Gruss called his circus Le Cirque à l'Ancienne, the Old-Time Circus.)There was obviously a strong planetary need for a circus renaissance: That same year (1974), in Adelaide, Australia, a young company of clowns, acrobats and aerialists that called itself "New Circus" began to perform and attract attention. It was followed a year later by the Soapbox Circus; both companies merged in 1977, to become Circus Oz. Meanwhile, in 1975, Larry Pizoni and Peggy Snyder launched the grassroots Pickle Family Circus in San Francisco, then the epicenter of the American counterculture movement.

Perhaps not coincidentally, all these changes came at a time when European intellectuals—mostly French—were fretting over the decline of the circus as a performing art. In 1975, Prince Rainier of Monaco (a longtime circus enthusiast) created the International Circus Festival of Monte-Carlo, whose Gold and Silver Clown awards would become to the circus world what the Oscar® is to the movie industry. It was followed in 1977 by Paris's Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain (World Festival of the Circus of Tomorrow), created to showcase and promote a new generation of circus performers, mostly trained in circus schools.

In this atmosphere, the Gruss/Fratellini model quickly stimulated other experiments. In 1977, Paul Binder and Michael Christensen, who had performed as jugglers with Fratellini, created the New York School for Circus Arts and its performing branch, the Big Apple Circus, which reintroduced the classical one-ring circus to America. The same year, Bernhard Paul and André Heller created Circus Roncalli in Germany, restoring the lost flamboyance of the German circus of yore.

In Montréal, Canada, Guy Caron founded the Ecole Nationale de Cirque (National Circus School) in 1980, and in 1984, Guy Laliberté created the innovative Cirque du Soleil, with Caron as its first Artistic Director. All were outsiders whose enterprises, each in its own way, were highly creative and gave a much-needed boost to the circus (and for Cirque du Soleil, a drastically different image). They also had a profound influence on the development of a "new circus" movement, which redefined the circus as a performing art, and on changes in the artistic and commercial attitude of many of the traditional circuses.In 1985, the French government created the Centre National des Arts du Cirque, a professional circus college on the Russian model. Other schools, often private not-for-profit entities and with varying degrees of professionalism, were established in England, Belgium, Sweden, Italy, Australia, Brazil, and the U.S., among others, adding their numbers to the circus schools already in existence in the former Eastern Bloc.

Although China has a 2000-year-old acrobatic theater tradition of its own, its many troupes—similarly to their Russisan counterparts—developed new training method]]s after the Communist revolution and found themselves welcome participants in the circus renaissance. Director Valentin Gneushev (certainly the most influential director in the contemporary circus) opened his own studio in post-communist Moscow, while others opened specialized schools, like André Simard's aerial-act studio, Les Gens d'R, in Canada.

Circus in the 21st Century

The surge of teaching activity led to the creation of a multitude of avant-garde and experimental circus companies in the last decades of the 20th century, especially in England, France, Germany, Australia, and Canada (some of them extremely successful, such as the French "heavy metal" circus Archaos, or the German Circus Flic-Flac), as well as to a revival of the old variety theater, especially in Germany with the resurgence of German "varieté(German, from the French: ''variété'') A German variety show whose acts are mostly circus acts, performed in a cabaret atmosphere. Very popular in Germany before WWII, Varieté shows have experienced a renaissance since the 1980s.".

Traditional circuses, however had to face a change of audience's perception regarding animal training, fueled in large part by animal-rights activists—in spite of massive positive changes in the presentation and keeping of wild animals, especially in Europe. This led to a swarm of local legislation that made it often difficult, and oftentimes even impossible for circuses to present wild animal acts. Many circuses had to adapt and gradually give up the presentation of animals, following in that the example of the very successful Cirque du Soleil.

However, in many countries, this had a devastating effect on the circus industry: large traveling circuses that relied in large part on their vast menageries and the presentation of their exotic and wild animals, where forced to dispose of them and eventually closed, thus putting animal trainers ans keepers out of work, and at the same time considerably reducing the employment opportunities for other artists. However, animal acts are still presented by many circuses, notably in Eastern Europe and in Russia, and wherever else they are offered, they largely remain audiences' favorites.

Nonetheless, the circus, which has always been a highly adaptable performing art, is today undergoing important cosmetic changes, but its appeal as an universal form of entertainment remains, and a new expansion is to be expected.

Suggested Reading

- Joseph Halperson, Das Buch von Zirkus (Düsseldorf, Ed. Lintz A.-G., 1926)

- Henry Thétard, La Merveilleuse Histoire du Cirque, 2 vol. (Paris, Prisma, 1947)

- Rupert Croft-Cooke and W. S. Meadmore, The Sawdust Ring (London, Odhams Press Ltd., 1951)

- Raul H. Castagnino, El Circo Criollo — Datos y documentos para su historia 1757-1924 (Buenos Aires, Lajouane, 1953)

- Tristan Rémy, Le Cirque et ses Etoiles (Bruxelles, Artis, 1955)

- Alessandro Cervelatti, Storia del Circo (Bologna, S.p.A. Poligrafici il Resto del Carlino, 1956)

- Alessandro Cervelatti, Questa Sera Grande Spettacolo (Milano, Edizione Avanti!, 1961)

- Evgueny Kuznetsov, Der Zirkus der Welt, translated from the Russian by Ernst Günther and Gerhard Krause (Berlin, Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, 1970 — Originally published as Цирк, Moscow, 1930)

- Alf Danielsson, Cirkusliv (Malmö, Askild & KUarnekull, 1974) — ISBN 91-7008-199-9

- Stuart Thayer, Annals of the American Circus — 1793-1860 (Seattle, WA, Dauven & Thayer, 1976, 1986, 1992, 2000)

- Dominique Jando, Histoire Mondiale du Cirque (Paris, Jean-Pierre Delarge, 1977) — ISBN 2-7113-0054-4

- Monica J. Renevey (Editor) and Collective, Le Grand Livre du Cirque, 2 vol. (Genève, Edito Service S.A., 1977)

- Henry Thétard, La Merveilleuse Histoire du Cirque, followed by Le Cirque depuis la guerre by L.-R. Dauven (Paris, Julliard, 1978) — ISBN 2-260-00138-6

- George Speaight, A History of the Circus (San Diego and New York, A. S. Barnes and Company, 1980) — ISBN 0-498-02470-9

- Anders Enevig, Cirkus i Danmark, 3 vol. (Copenhagen, Dansk Historisk Håndbogsforlag, 1982) — ISBN 87-85207-59-4 and ISBN 87-85207-61-6

- Mark St Leon, Sprangles & Sawdust — The Circus In Australia (Richmond, Victoria, Greenhouse Publications, 1983) — ISBN 0-909104-61-1

- LaVahn G. Hoh & William H. Rough, Step Right Up! — The Adventure of Circus in America (White Hall, VA, Betterway Publications, 1990) — ISBN 1-55870-140-0

- John Culhane, The American Circus, An Illustrated History (New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1990) — ISBN 0-8050-1647-3

- Per Arne Wåhlberg, Cirkus i Sverige — Bidråg till vårt lands kulturhistoria (Stockholm, Carlsson Bokförlag, 1992) — ISBN 91-7798-591-5

- Beatriz Seibel, Historia del Circo (Buenos Aires, Ediciones del Sol, 1993) — ISBN 950-9413-46-1

- Pascal Jacob, Le Cirque — Du théâtre équestre aux arts de la piste (Paris, Larousse, 2002) — ISBN 2-03-505168-1

- Dominique Mauclair, Planète Cirque (Baixas, Balzac Editeur, 2002) — ISBN 2-913907-10-5

- Julio Revolledo Cárdenas, La Fabulosa Historia Del Circo En México (Mexico, Escenologia A.C. - Conaculta, 2004) — ISBN 968-7881-47-X and ISBN 970-35-0378-0

- Raffaele de Ritis, Storia del Circo — degli acrobati egizi al Cirque du Soleil (Roma, Bulzoni Editore, 2008) — ISBN 978-88-7870-317-9

- Julio Revolledo Cárdenas, El Siglo de Oro del Circo en México (Madrid, Ed. Más Diffícil Todavía, 2010) — ISBN 978-84-477-1078-2

- Mark St Leon, Circus — The Australian Story (Melbourne, Melbourne Books, 2011) — ISBN 978-1-877096-50-1

- Pilar Ducci González, Años de Circo — Historia de la Actividad Circense en Chile (Barcelona, Circus Arts Fundation, 2012) — ISBN 978-84-477-1155-0

- Susan Weber (editor) and Collective, The American Circus (New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2012) — ISBN 978-0-300-18539-3

- Sylke Kirschnick, Manege Frei! — Die Kulturgeschichte des Zirkus (Stuttgart, Konrad Theiss Verlag GmBH, 2012) — ISBN 978-3-8062-2703-1

- Linda Simon, Greatest Shows on Earth — A History of the Circus (London, Reaktion Books, Ltd., 2014) — ISBN 978-1-78023-358-1

- Gisela Winkler, Von Fliegenden Menschen und Tanzenden Pferden, 2 vol. (Grandsee, Edition Schwarzdruck, 2015) — ISBN 978-3-935194-71-6 and ISBN 978-3-935194-70-9

- Dominique Jando, Philip Astley & The Horsemen who invented the Circus (A Circopedia Book, 2018) — ISBN 978-1-98404131-9